When Xi Jinping presided over a collective study session of the Politburo on “international communication work” last May, urging his comrades to “build a credible, lovable and respectable image of China,” he probably did not envision telling the story of a teenage girl resurrected from the dead on a journey of revenge across a post-apocalyptic American landscape. But this, say some enthusiastic young Chinese, is the real way into the hearts – and the pockets – of global gamers, and perhaps a more effective way of “telling China’s story well.”

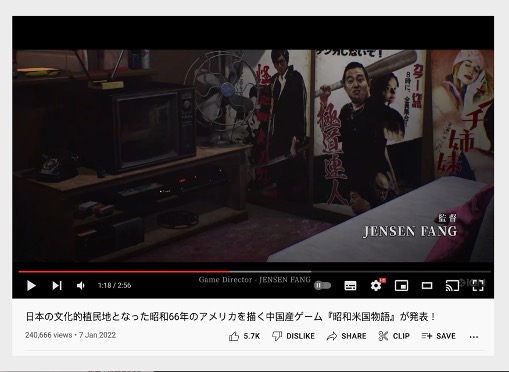

Meet Choko, the gun-slinging protagonist of “Showa American Story,” a role-playing game (RPG) developed and produced by NEKCOM Games, a Chinese game developer based in Wuhan. Due for release this year on major gaming platforms such as PS4 and Steam, the game unfolds in a United States that has become, as the company says, “an unofficial colony of Japanese economics and culture.” (Readers who wish to know what that looks like will have to endure the game’s trailer, which recently racked up more than 240,000 views on the YouTube channel of IGN Japan, a popular video gaming website).

In an interview with Shanghai’s Guancha Syndicate earlier this month, NEKCOM founder Luo Xiangyu (罗翔宇) stressed the game’s unique Chinese perspective, and his remarks kicked up a flurry of discussion over the most effective means of “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国的故事), a concept that since 2013 has been at the heart of the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to increase China’s international discourse power.

“We wanted to do something that was centered on the popular culture of the 1980s with a lot of American and Japanese culture,” Luo told Guancha Syndicate. “But we wanted to approach it from our own Chinese perspective.”

Luo explained that in his view “the Chinese interpretation of other subjects is itself a part of Chinese values and culture.” If Western and Japanese filmmakers and game producers could make entertainment products like the DreamWorks animation “Kung Fu Panda,” or drawing on Chinese classics like Romance of the Three Kingdoms, then why couldn’t China draw cultural strength by turning the tables?

“I think the way one web user put it online is really good,” Luo explained. “They said, ‘Telling China’s story well isn’t necessarily about telling Chinese stories. This is exactly the way we think about it.”

This re-interpretation of Xi Jinping’s external propaganda concept quickly drew praise online, the discussion directed in part by the clickbait headline at Guancha News: “Chinese Team Develops Game About ‘Japanese Culture Colonizing America’: Telling the Chinese Story Well Does Not Necessarily Mean Telling Chinese Stories.”

“It’s great that we are supplying games with content neither Japan nor the US would dare to do,” one user commented. Another added: “It seems that only a Chinese company could make a game like this. RPGs with Chinese characteristics!”

“It’s true that to tell the Chinese story well doesn’t necessarily mean using Chinese stories,” another user wrote. “The concepts we want to convey cloaked in their culture can also do the job.”

These users are not far off the mark when it comes to the growing importance of Chinese game exports for the development of “national cultural exports” (国家文化出口), regarded by the CCP as a key component of national discourse power.

In a notice on support for the development of “national cultural export bases” (文化出口基地) released in October 2021 by the Central Propaganda Department and 16 other departments, the government named video games on its list of encouraged exports for “going out” (走出去), which also included traditional cultural products, films and television dramas as well as other digital cultural products. Products in these categories were to be provided with financial assistance, and other enterprises were encouraged to offer services supporting the “going out” process, including printing, translation, post-production and so on.

Also in October, the propaganda department of Shanghai municipality announced the results of its push to allocate “special support funds” for various cultural product exports. The project support fund, called “Chinese Culture Goes Global” (中华文化走出去), received 220 applicants, from which 58 projects were selected for support. Five of these projects were games, including the popular game “Mr. Love: Queen’s Choice” (恋与制作人), a visual novel mobile game.

Just last month at the “Guofeng Game Forum” (国风游戏论坛), hosted by the China Audio-Video and Digital Publishing Association (CADPA), an ostensible “non-profit social organization” under the Central Propaganda Department, representatives from major gaming producers, including Tencent and Yoka Games, gathered to discuss the integration of game products with traditional Chinese culture. The goal was to inspire more developers to “manifest the charms” of traditional culture in order to “create high-quality national style games to tell the Chinese story well and spread the voice of China well.”

But some fans of the concept of “Showa American Story” – who must now wait for the game’s formal release – might advise propaganda officials to drop the obsession with traditional Chinese culture. Who says China can’t find discourse power on a post-apocalyptic desert highway in the American West, where zombies and monsters must be dispatched through brutal combat against the backdrop of Japanese billboards?

“People only listen when you tell fun stories,” one user commented at Guancha Syndicate. “Don’t make any more of that stuff just telling stories to yourself. That’s formalistic cultural garbage that pulls the wool over your own eyes.”