How is Environmental Journalism Doing in China’s Worsening Media Climate?

Kevin Schoenmakers

Hongqiao Liu

Kevin Schoenmakers: How did you become an environmental reporter?

Hongqiao Liu: I majored in journalism and communication as an undergraduate, and I always wanted to become an investigative journalist and cover conventional investigative topics like corruption. When I joined Caixin as an intern, I was assigned to the environment and science desk. It wasn’t my first choice but I stayed.

I left Caixin — and journalism — after four years, in 2014, and started working for non-profits, think tanks, and freelancing.

Kevin Schoenmakers: Why did you decide to leave journalism?

Hongqiao Liu: The media environment was never ideal but at that time I really felt I couldn’t continue working as an investigative environmental journalist. I’d seen enough stories get killed in the newsroom and I didn’t want to repeat that. I also felt powerless, that being a journalist and uncovering stories alone wasn’t sufficient to solve any problems.

So I decided to work with non-profits who actually talk about issues directly with stakeholders such as the government, investors, and the business community, and who propose solutions and bring about change. I still occasionally wrote long-form articles. For example, I covered wildlife trafficking from northern Vietnam into China.

Kevin Schoenmakers: How much, would you say, do Chinese media companies invest in their environmental coverage and how has this changed over time?

Hongqiao Liu: Back in 2010, environmental news was an emerging beat in Chinese newsrooms. Outlets like Southern Weekly, Caixin, and Caijing, as well as many commercial local media, had dedicated pages and reporters. I think that time was the heyday of environmental journalism. There was a lot of interaction between journalists and civil society to bring some environmental crises to the attention of the public and onto the policy agenda, which would push the government to make substantive changes.

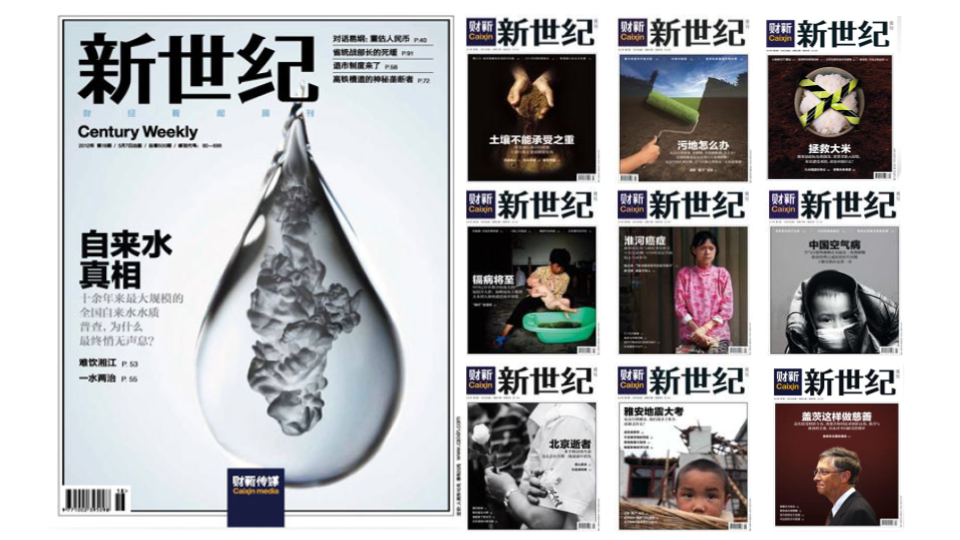

For example, in 2012, we wrote about tap water quality for my first cover story in Caixin, “The Dirty Truth of Tap Water.” Our primary source was a survey of China’s water quality conducted by a government-affiliated research institute which had never been made public. At the same time China had set itself a deadline to meet a new, strict standard for drinking water quality. We examined how far away we were from meeting this standard, and illustrated the public health consequences of drinking contaminated water.

That was probably the only magazine that Caixin has ever had to reprint. Every outlet in China, from official media to city media, picked up this story and questioned local governments about their water quality. Civil society groups started to demand transparency and government accountability. Soon after that, the ministry in charge of water quality talked with an official outlet and addressed some of the questions we had raised in our coverage — without naming us. They later invested heavily in improving urban water infrastructure.

So at that time, in 2012, there was still a relatively healthy ecosystem for journalists to do their jobs. Experts supported their work, civil society and other media would pick up their stories, and the government would, to an extent, address the issues they raised. In 2014, when I left my job, that relatively healthy environment had worsened rapidly.

That was probably the only magazine that Caixin has ever had to reprint. Every outlet in China, from official media to city media, picked up this story and questioned local governments about their water quality.

Kevin Schoenmakers: Has there been any change since 2014?

Hongqiao Liu: Media devote less space to environmental reporting. There is also a widespread shortage of specialized staff. This mirrors the general [worsening] media environment. It’s almost unheard of now to have a single story trigger a wave of responses in the way our tap water quality story did.

In terms of support, let me give you an example. For quite a long time, Chinese newsrooms have barely sponsored any coverage of the annual UN Climate Change Conferences, because they don’t have enough funds or don’t think it’s an important enough issue. Environmental journalists have to rely on outside funding, such as grants. Besides foreign correspondents from state media — who aren’t specialized in this topic — Chinese journalists have long been largely absent from these events.

And then there are investigations within China, where a reporter spends weeks or even months on the ground like I did with my colleagues at Caixin for a series on cadmium-polluted rice. Starting from before I joined, the environment desk spent three to four years following that story very intensively. This is barely imaginable these days. I don’t see any stories of this scale or length in Chinese media. But that doesn’t mean such issues are gone.

Even on climate change, coverage is mostly sponsored by foundations or corporations. They mostly fund popular science-type articles on climate change or articles that promote corporate innovations rather than reporting in the field, telling stories about climate refugees or looking into sources of emissions.

Even when I was at Caixin, in cases when they wouldn’t support this type of story, I would apply for external reporting grants. But gradually such grants have gotten much more sensitive, because their funding comes from outside of China.

I don’t know if it’s even accurate anymore to describe the media environment in China as an ecosystem. It’s long gone.

Kevin Schoenmakers: What about reader interest in environmental stories? What is the trend there? A study from 2019 showed that Chinese people aren’t as interested in climate change compared to people in other countries.

Hongqiao Liu: I don’t write for the Chinese audience anymore, so I’m not really in a position to answer that question.

There are different surveys showing Chinese people are actually very concerned about climate change, but their understanding of what climate change is and how it could impact their life varies. A recent study among university students showed that they are concerned about climate change, that they would like to change their consumer behavior, but that they are not well-informed on the issue.

I don’t know if it’s even accurate anymore to describe the media environment in China as an ecosystem. It’s long gone.

Because the Chinese government has made climate change a top policy priority, we don’t see as much climate skepticism in China as elsewhere. We do see a different, quite popular narrative that goes, “Climate change is real, but we are an emerging economy that has the right to develop, and climate change is an excuse used by hostile western forces to limit our development.” It is challenging to unpack climate change, an abstract phenomenon, for a Chinese audience in this particular media environment.

Kevin Schoenmakers: My impression is that last year’s Zhengzhou floods, during which extreme rainfall resulted in the deaths of close to 400 people, were a wake-up call for China. Has that led to more coverage of climate change?

Hongqiao Liu: Zhengzhou was a wake-up call. The floods affected people’s lives to an extreme degree, and they impacted food supply and nationwide logistics. Social media also played a role. It broke through the wall of information control, allowing people to directly see how destructive and serious the floods were, rather than just reading statistics about the number of deaths. An average person sitting somewhere in an air-conditioned room could still experience and empathize with this tragedy caused by climate change-amplified extreme weather.

So in a way, it was a wake-up call, but we had been building up to this moment over the last few years. Before Zhengzhou, in 2020, there was also a series of floods in the south of China, but they didn’t get as much coverage at that time, immediately after the start of the pandemic.

There are more media resources now for covering climate change, but less so for other environmental issues. Ten years ago, we covered a lot of issues relating to air pollution, water pollution, soil pollution, and food safety. Those issues are still there, but they are more expensive and more difficult to cover. So, right now, climate change is the go-to topic.

For example, “The Intellectual” (知识分子), a non-profit media outlet that is very popular in China, has hired a dedicated journalist and editor just to cover climate change. Caixin has started an ESG channel that also picks up a lot of news on the environment and climate change. [Note: ESG stands for environmental, social and corporate governance, and is a set of standards applied by socially conscious investors to study potential investments.]

However the challenge is still that the media is not an attractive industry for professionals and investors. News coverage of climate is not profitable. You have to find alternative ways to finance it. There is no ecosystem to support — relatively — independent journalism. From the government to companies, they all have a demand to “strategically communicate” their positions on climate change, be that national policy or corporate strategy, but a crucial link is missing, which is journalism. We need media organizations to fulfill their role of the fourth estate, to ask the uncomfortable questions and to hold parties accountable, especially in China. But newsrooms are much weaker today compared to 2010.

Kevin Schoenmakers: Over the past decade, the Chinese government has become much more concerned with solving environmental issues — for example, they have made their climate pledges, and they have done a lot to reduce air pollution and water pollution. At the same time it seems that reporting on environmental issues has become more sensitive. What explains this apparent contradiction? You might think that if it’s so important for the government to solve environmental issues they would also welcome more reporting.

Hongqiao Liu: Back in 2010, when I was assigned to cover environment and science, I was told — and I also thought to myself — that it was a relatively safe choice, compared to other more traditional investigative beats.

One of my first big stories at Caixin, when I was 20 years old, was about villagers who had set themselves aflame in resistance to a local government-led land grab. After spending a few minutes on the rooftop of the family’s house, where the incident had occurred, I immediately realized that I was followed and had to drop everything and escape. It was traumatizing. [Note: This was the now-famous Yihuang self-immolation case, seen for a number of years as a sign of the power of microblogging platforms.]

Compared to such experiences, environmental journalism at that time was safer in terms of personal security. I was able to carry out most of my investigations smoothly, if discreetly, and with some luck. I was able to push issues like cadmium-polluted rice, and other heavy-metal issues, onto the public agenda and trigger policy changes without exposing myself to much risk.

Back in the early 2010s, environmental reporting played a crucial role in informing the public about pollution’s effects on their own health. According to political scientists, people’s desire for a cleaner environment created mounting pressure on the government and challenged the legitimacy of the CCP’s rule. It was a defining moment in China’s environmental movement. Ultimately, this was the main reason why Xi Jinping decided to invest so much in tackling climate change.

Journalism at that time enabled social change. I don’t think that’s the case anymore. That’s not because the function of environmental journalism has changed, it’s because journalism’s ecosystem has deteriorated a lot in China. The government has made reporting in general much more difficult. Journalists have to follow the script.

At the same time, the government and the party have made the “ecological civilization” drive and the climate pledges their top agenda priorities, and Xi Jinping is personally invested in promoting these issues. Questioning the implementation of these policies, or debating certain policy or technology choices, have become much more sensitive.

Journalism at that time enabled social change. I don’t think that’s the case anymore.

Kevin Schoenmakers: Besides dealing with censorship, are there any ways in which environmental reporting in China is different from environmental reporting in other countries?

Hongqiao Liu: The issues are different, the national circumstances are different, and there is not much exchange and support. There is no network of environmental journalists in China. There used to be informal groups.

Elsewhere, for example in Southeast Asia, there are a lot of independent environmental journalist networks and initiatives where journalists cooperate across borders to tackle issues whose impacts go beyond one country’s territory. We don’t see that much in China anymore. That is crucial. China’s environmental issues have expanded beyond its own territory along with China’s foreign outbound economic activities, such as the Belt and Road Initiative. But coverage that tracks issues beyond China’s border is dominated by journalists based outside of China. That’s a pity, I think.

There is also not much exchange of investigative techniques, tactics, or tools. When I go to events organized by the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN), the investigative methods they discuss aren’t compatible with the Chinese context. We have our own Google, our own Twitter. And our skills, tactics, and experiences of conducting investigations in China are often not acknowledged by the international journalism community either.

There is this huge training gap for younger generations of Chinese journalists. In the rare cases they decide to pick up covering the environment, there are very few resources to help them develop their skills, to grow, to develop, and also to take care of their mental health.

Kevin Schoenmakers: In your early career you reported in China for Chinese readers. Now you’re writing about China for foreign readers. Why did you decide to make this change?

Hongqiao Liu: I returned to journalism in 2021, and spent one year at Carbon Brief. After seven, eight years working with a number of non-profit organizations, I realized that what is most lacking today is not research, campaigning, or strategic communication but independent journalism on China’s environmental and development challenges.

That was just a few months after Xi Jinping made his pledges. And since then I had read a lot of misinformed coverage by international media. On this specific topic, which is very technical and complicated, the shortage of expertise and the dominance of politicized narratives are big problems. For me, climate change is the most important issue of our century. It is an issue the rest of the world cannot figure out without China. I felt I had to fill that gap, to explain the logic behind China’s policies, the dynamics within China’s system, and to give credit and criticism where they are due.

I care about China. I care about climate change. I hope climate change will remain an area of cooperation between China and the rest of the world. I know from my own experiences how powerful journalism can be. We have to use it wisely to enable the green transition to happen.

Kevin Schoenmakers