The middle school in Yingxiu, which lost 5,000 of its 12,000 population in the 2008 earthquake. Image by David and Jessie Cowhig available at Flickr.com under CC license.

Last month brought the 14-year anniversary of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, an unprecedented disaster that tested the limits of censorship and the professional capacity of a new generation of Chinese journalists. Each year the anniversary of the quake on May 12 is commemorated in China’s media, with special tributes as well as follow-up reports on how communities impacted by the quake are thriving today.

But for many of the hundreds of Chinese reporters who reported from the scene in Sichuan, the anniversary of the quake is a reminder that they have now left important work behind as the pressures on professional journalism in China have grown.

In a post commemorating the anniversary of the quake this year, the WeChat official account “Media Training Camp” (传媒特训营) reached out to Chinese journalists who reported on the disaster 14 years ago. The post, “Those journalists who covered the Wenchuan earthquake have all essentially changed professions,” was just the latest in a number of posts in recent years that have taken the anniversary as an opportunity to reflect on the state of the journalism profession in China today, as well as the role of the media in disaster reporting.

Volunteers on the Front Lines

One of the reporters profiled in the “Media Training Camp” post, Feng Xiang (冯翔), was working as a senior reporter for a metropolitan news outlet in the northeastern city of Shenyang at the time of the earthquake. As news of the quake reached Shenyang, Feng remembers constantly reading early reports in which the projected death toll seemed to rise and rise. He thought of The Great Tangshan Earthquake (唐山大地震), the seminal work of reportage by writer (and CMP co-director) Qian Gang, a book that detailed the only earthquake in China’s recent history with a comparable scale of devastation.

Feng’s newspaper did not immediately dispatch reporters to the scene. In fact, there had been an explicit prohibition early on from the Central Propaganda Department instructing media not to send reporters but to rely instead on official news releases. But a few days after the quake, Feng’s paper began doing what many other media across the country were doing – it sent reporters to Sichuan imbedded with various rescue and response teams or other groups. Some, for example, might join firefighting brigades while others went along with medical teams.

“I went as part of a volunteer group, taking a few other volunteers along,” Feng recalled. “[We] went a bit later, so we didn’t see the most tragic scenes, and were mostly involved in subsequent follow-ups.”

When Feng and the volunteers arrived, they realized local media and officials were completely unprepared to help coordinate their activities, so they had to improvise based on what they encountered. “We would help elderly people set up their tents, for example, or help transport the injured, that kind of thing,” Feng recalled. “Along the way I wrote some reports, and aside from those, I also reported on the progress of provincial rescue and rebuilding efforts, and about certain things and people that had become famous due to the quake.”

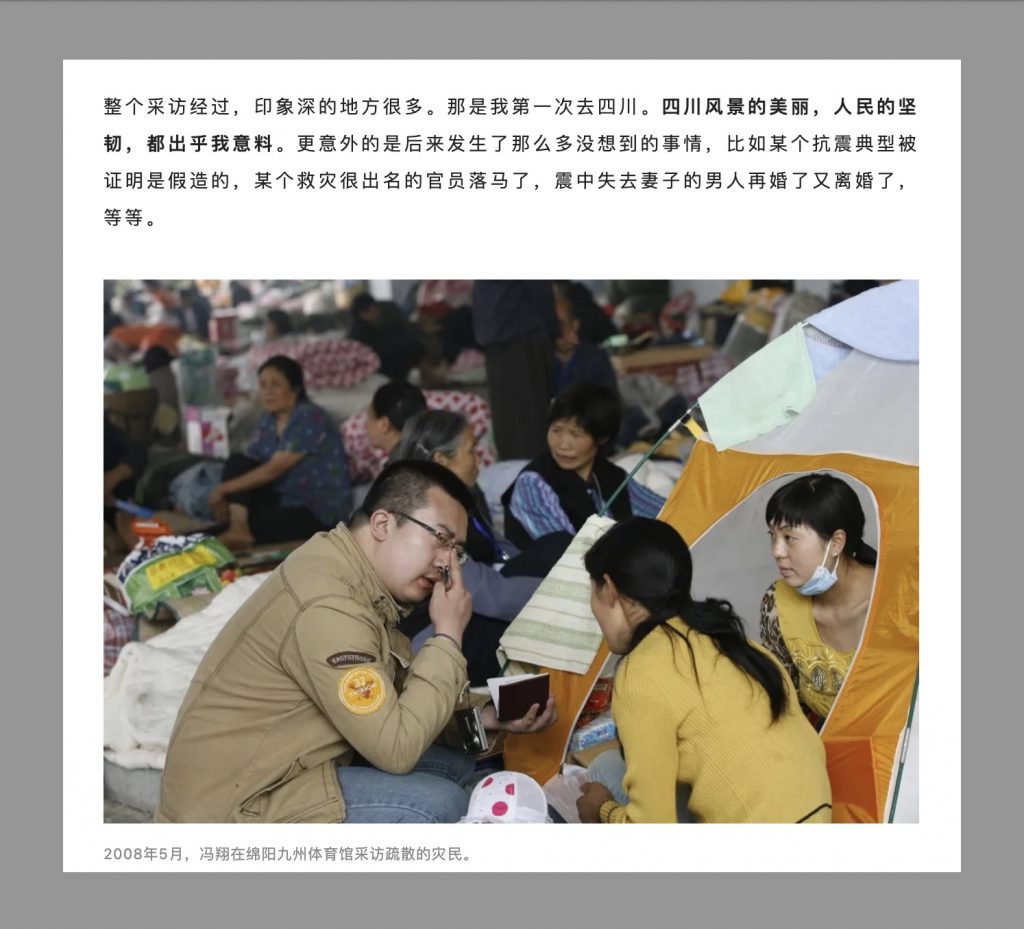

The trip to Sichuan was Feng’s first, and many things made a deep impression in him, he told “Media Training Camp,” including the natural beauty of the province and the resilience of the people. But one of the most enduring impacts on journalists, said Feng, was a tempering of their idealism as simple narratives of tragedy and heroism were complicated by revelations in the media.

“I never expected all of the surprises that came later,” said Feng. He noted, for example, the subsequent discovery – thanks to media reporting – that certain exemplary figures upheld during the earthquake response had been faked, and that some officials given credit during the quake were ultimately removed for their role in shoddy construction or other forms of corruption.

In the aftermath of the Wenchuan earthquake, hard-nosed reporting by ambitious professional news outlets such as Caijing and Southern Weekly, as well as investigations by civil society, were instrumental in bringing many of the systemic errors behind the disaster to light.

“After seeing these things happen, those of us journalists who witnessed the disaster first-hand from the start also underwent a change,” said Feng. “We were no longer so hot-blooded and idealistic, and we had a better understanding of human nature and the current state of our country.”

Enlisted in the Official Narrative

In some cases, the idealism and professionalism of journalists heading to the front lines following the Wenchuan earthquake were tested by the demand that they be complicit in government messaging. In 2018, marking the ten-year anniversary of the quake, journalist Zhao Jiayue (赵佳月), who reported for Guangdong’s official Nanfang Daily (南方日报) during the disaster, told her own such story on her WeChat official account.

Zhao described how, once back from the site of the quake, where she had seen the devastation in places like Yingxiu first-hand, she was presented by the government in Guangdong as a “model” (典型) for the earthquake response. She had to constantly deliver related propaganda reports to officials – “preaching like Aunt Xianglin,” she said, referring to a famous character from modern Chinese fiction who performs her grief again and again. She was obliged to deliver Powerpoint presentations, crying when tears were called for, and clapping when applause was called for.

These experiences, both the reporting of the disaster and its manipulation, had a strong psychological impact on many of the journalists who went to Sichuan. By 2018, Zhao and her husband, a news photographer, had been out of journalism for several years, opening a small bed and breakfast.

“Of that first batch of journalists who rushed to the epicenter to report on the earthquake 10 years ago, almost all have chosen different career paths now, and investigative journalism has almost completely disappeared,” Zhao wrote.

The loss of in-depth reporting and investigation had to do partly with the controls exercise by the authorities. But another thread in the story was the broader change brought about by the decline of traditional outlets and the rise of new digital platforms, such as the so-called “self-media” (自媒体), that prioritized clicks over reported substance. “All scenes of vividness, urgency and tragedy in cases of disaster are buried these days in the 100,000+ likes received by articles marketed through self-media,” Zhao wrote.

Moving On from Journalism

Another reporter from the frontlines of the 2008 earthquake, Lin Tianhong (林天宏), also remembered the quake as a heyday for in-depth and investigative journalism in China. In an interview three years ago with Q Daily (好奇心日报), a digital publication that was shuttered in November 2020 owing to commercial and political troubles, Lin explained how he was sent to Sichuan shortly after the quake to report for the

China Youth Daily (中国青年报) newspaper.

As Lin made his way toward the township of Yingxiu (映秀镇), a town near the epicenter that had been hit especially hard, he came across groups of people fleeing the town. Among them was a middle-aged man carrying a teenager across his shoulder. Lin offered to help the man carry the boy, but the man simply said: “It’s ok, he’s my son and he is dead.”

Based on this encounter, Lin wrote a feature story for Freezing Point (冰点), a well-regarded supplement of the paper, called “Going Home” (回家). “Through the limited 30-year span of my living, I had accumulated some understanding of life, and some reverence for death,” Lin wrote in the story. “But I suddenly realized that this had collapsed, just as had the shattered ruins before me.”

Lin Tianhong’s feature story was a huge success, stirring readers across the country and winning him several journalism awards.

But even though the quake brought Lin professional acclaim, the experience after the Wenchuan quake fundamentally changed his attitude toward investigative journalism in China. This was not necessarily about government restrictions on the practice, or about wider changes in the media industry. It was also about a new perspective on life and value.

Once he was back from Sichuan, Lin found that he was no longer interested in the regular selection of topics on the editorial desk. His whole understanding of things had changed radically after the earthquake, and he no longer cared for many topics that had interested him before the experience.

“This piece gave me instant fame, and I became someone everyone, both at the newspaper and in the broader industry, felt could write well,” he told Q Daily. “But I also experienced a change.”

“I had seen life and death, and I felt that so many things, like money, or like buying a house and falling in love, were all bullshit,” he said.

After changing to several new positions at different media, including China Weekly (中国周刊) and Portrait (人物), Lin left the media industry in 2014. He joined Wanda Group, the Chinese multinational conglomerate, where he worked on the company’s internal newsletter.

A major transition was underway in China’s media by 2014, with the rapid growth of the internet and high-tech, and the expansion of social media platforms such as WeChat (launched in 2011). Like Lin, many other journalists rushed for the exit that year. “2014 was really the year from when traditional media workers transitioning was the trend,” Lin recalled. “Quite a few of my good friends in the media have left since for roles in public relations at places like [tech giant] Alibaba.”

Shaky Ground for Disaster Reporting

Owing to a combination of the abovementioned factors, including government control and propaganda, broader media transformation and professional disenchantment, many journalists have abandoned the industry over the past decade. This shift has had a noticeable impact on disaster reporting in recent years.

Recent disasters in China, including catastrophic flooding in Henan in July last year, and the crash of China Eastern Airlines flight MU5735 earlier this year, have not received the level of coverage by professional outlets – many of them commercial newspapers and magazines – that could be seen in the case of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake.

In the midst of the rescue and recovery effort that followed the MU5735 disaster back in March, some journalists tried to reach the scene, as they had in 2008. However, they were turned back by local authorities, while state-run media such as Xinhua and China Central Television were provided with full access, enabling them to effectively direct the narrative.

When a small number of news media, including China Youth Daily and Portrait, attempted to follow up on the disaster by telling human stories about the victims, this prompted a fierce discussion online about the limits of disaster coverage. Many netizens criticized a feature story by Portrait on the grounds that its intimate reporting of the lives of victims violated journalistic ethics by capitalizing on the trauma of those close to the victims. In fact, the report was similar to stories like Lin Tianhong’s that followed the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake.

But public attitudes about disaster coverage seem to have changed as media generally have been subjected to more questioning. As the controversy continued over the Portrait feature story in March, Phoenix News (凤凰新闻) reached out to journalism school students in China for their views. Many voiced hesitation about choosing journalism as their future career path.

One journalism student summed up the complex of challenges facing the journalist in China today, from low salaries and tight content controls, to the risk of personal attack from nationalistic internet users who balk at any and all critical coverage.

First, there was the question of adequate pay. “Being a journalist doesn’t offer value for money these days,” they said. “One of my journalism teachers told me his [annual] salary today is just 3,000 RMB higher than it was 15 years ago, even though living expenses have increased exponentially across the board – and often he can’t make ends meet.”

Next up, came the issue of pressures from the government, and from ubiquitous online trolls. “Even so, to complete a news piece that gets at the truth as much as possible, you have to put in so much more effort than before. Aside from [the difficulties of] on-the-scene investigation, once you’ve published a piece you also have to endure accusations, and sometimes even personal attacks, from those ‘keyboard warriors.’”

“With this total imbalance between rewards and costs, ‘passion’ becomes the only thing keeping you in this industry.”