China Newspeak

No Class War Please, We’re Communists

“For years, the regular ‘Clear and Bright” (清朗) online cleanup campaigns of China’s top internet control body have been a constant reminder to platforms and citizens to keep their behavior in check. But in recent months these campaigns have come with such dizzying frequency that keeping track of them has become a daunting task.

The latest case in point is an expansive list of regulatory priorities released earlier this month that includes not just concerns such as doxxing and cyberbullying — shared by regulators and citizens around the world — but also vague value labels that have the authorities at the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) meddling directly into areas such as “regional prejudice,” “gender antagonism,” and “class antagonism.”

Here’s a quick look at some of the most contentious forms of conduct identified in this latest “Clear and Bright” campaign.

Gender Antagonism (性別對立)

“Gender antagonism” (性別對立), identified as a key target of the latest Clear and Bright campaign, is a well-established dog whistle for feminism. The accusation has frequently been brought against women’s rights activists in China, framing their actions as a cantankerous attempt to upset harmonious relations between men and women.

In 2020, stand-up comedian Yang Li (杨笠) was censured for “creating gender antagonism” after a set that took digs at men. The following year, the official Xinhua News Agency was up in arms about an online discussion about whether Chinese-Canadian Sinologist Florence Chia-ying Yeh (葉嘉瑩) should be referred to with the honorific xiansheng (先生), which is typically translated as “mister” but is also more generally a term of respect for teachers.

“There are no winners in gender antagonism,” the newswire said.

A related criminal charge often brought in such cases is “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (尋釁滋事), which targets perceived threats to the political and social order. The “Feminist Five” (女權五姐妹) were detained on suspicion of “picking quarrels” on International Women’s Day in 2015 ahead of a planned campaign against sexual harassment on public transportation. The charge itself has historical roots in the equally notorious crime of “hooliganism” (流氓罪), which was extensively abused during the Maoist period from the 1950s to the 1970s as a pretext to punish political dissidents and persons suspected of immorality such as sexual minorities.

“Gender antagonism” is the latest permutation of this long-running crackdown on feminism, which has only intensified in recent years in the wake of the abortive MeToo movement in China. Its inclusion in this latest Clear and Bright campaign is a sign of consistency if nothing else, but it raises serious questions about how the authorities will apply this vague standard to perfectly legitimate and well-founded concerns about the treatment of women in society.

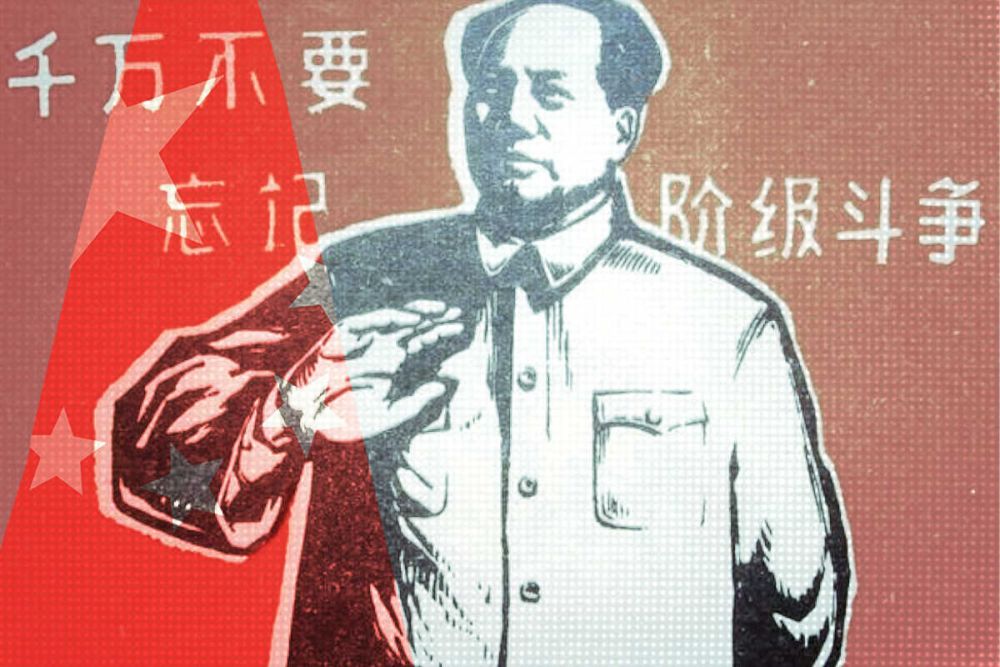

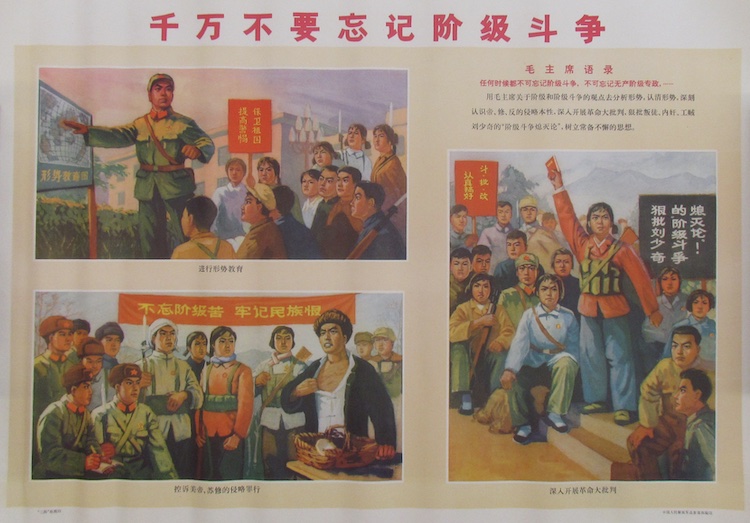

Class Antagonism (階層對立)

Another vague category of online conduct the CAC notice cautions against is “class antagonism,” a turn of phrase with a hint of irony considering it was the CCP that for decades waged all-out class struggle (階級鬥爭) under Mao Zedong, who professed that social transformation had to be “long and tortuous” for it to be truly meaningful.

Notably, however, the word used for “class” in the CAC notice is not the jieji (階級) of Mao’s class struggle but rather jieceng (階層), which can also be translated as “strata.” Although largely interchangeable in everyday usage, the two differ significantly in sociological theory. While jieji relates to Marx’s notion that there are only two classes — the proletariat and bourgeoisie — jieceng invokes the work of Max Weber, who saw class as a more complex outcome determined by both economic and non-economic factors such as social prestige and political power.

It may seem contradictory for an avowedly Marxist Party-state to speak of social stratification in such an un-Marxist way, but it is a necessary conceit.

It may seem contradictory for an avowedly Marxist Party-state to speak of social stratification in such an un-Marxist way, but it is a necessary conceit. How else do you reconcile the official CCP line that they have eliminated meaningful class distinctions with the reality of a highly unequal society with the highest Gini coefficient in the region? How else do you take seriously a “dictatorship of the proletariat” that vows to crack down on something like “class antagonism?”

The CAC is bringing this curious example of doublethink into the digital age. But the notion itself is not new. For decades, the CCP has glossed over this internal contradiction to reconcile China’s market reforms with the CCP’s unrelenting grip on power.

How the Class War Was Won

At the outset of the era of “reform and opening up” in 1978, the CCP’s Central Committee officially replaced Mao’s perpetual class struggle approach with former president Liu Shaoqi’s theory, which held that after the success of China’s proletarian revolution, the remnants of the bourgeoisie could be transformed into good socialists without violent class struggle.

Liu’s idea, when he first proposed it in 1957, was far ahead of its time. During the messy aftermath of China’s forced collectivization, Liu told the nation it was time to make economic development their top priority. “The enemies have been eliminated, the landlord and bourgeois class have been eliminated, the anti-revolutionary has also been eliminated,” he said. “Fundamentally. the class struggle in our country is over.”

A decade later, Liu Shaoqi was targeted by Mao’s Red Guards, who labeled him the “commander of China’s bourgeoisie headquarters” and a traitor to the revolution. He died in prison in 1969 due to complications from diabetes, his posthumous vindication still another decade off.

When the PRC promulgated a new constitution in 1982, it added this line, almost quoting Liu verbatim: “In our country, the exploiting class, as a class, has been eliminated.” The idea that China in the throes of breakneck, market-oriented reform was a post-class society was, of course, a fiction — but, arguably, a benign one. It enabled the country’s rulers to put the chaos of Mao’s reign in the past and focus on the economy, without undermining the very foundation of their own rule.

It has also stood the test of time. When Xi Jinping spoke last year about the need to “promote harmonious class relations” and “do a good job of United Front work among new social classes,” he spoke exclusively in terms of jieceng. After all, a jieji can encompass multiple jieceng, so one can recognize the emergence of “new jieceng” — referring to workers in the gig economy, new media, and other emergent industries — without acknowledging the persistent and embarrassing existence of entrenched classes that seem only to be growing further apart.

As the above foray into the history of CCP thinking on jieji and jieceng shows, class divisions and their political framing are thorny and complicated issues. And if the central authorities like the CAC have their way with prohibitions against “class antagonism,” no one inside China will be talking it out.