When push comes to shove in China, it is the powerful state-run news networks that get to dominate the story, with the blessing of the country’s leaders. But a case yesterday of real-life pushing and shoving involving the country’s official broadcaster, China Central Television, has stirred uncharacteristic questions about the role of journalists and their relationship to the public — and what rights they should and do have.

The scene unfolded yesterday as a news reporter from CCTV, the chief state broadcaster under the party-run China Media Group (CMG), and her filming crew were hustled away from the scene of a deadly gas explosion in Yanjiao (燕郊), a town in the central province of Hebei, about 50 kilometers east of Beijing. Video of the live broadcast on CCTV-2, which has been shared widely across social media in China, shows the reporter, clearly holding a microphone labeled “CCTV,” speaking calmly from outside the scene of the explosion when she is suddenly surrounded by uniformed personnel who block the camera and interrupt the broadcast.

As the live broadcast cuts back to the studio in Beijing, the anchors, clearly caught off guard, blandly remark on the need to, “Mind your safety.” Such a scene would be jarringly unusual to Chinese television audiences accustomed to more scripted and uneventful exchanges on official news programs.

As the clip made the rounds on social media, it drew anger from some, who criticized the actions of the local authorities. “As an old journalist myself, I am very supportive of the CCTV reporters who rushed to the scene of the Yanjiao explosion site this evening to report live,” wrote Hu Xijin (胡锡进), the former editor-in-chief of the state-run Global Times newspaper. “At the same time, I resolutely object to local police obstructing the report and expelling the reporter.”

For others, mindful of the special privileges that have been historically enjoyed by state media journalists, the incident was a wake-up call to a problem suffered for decades by more professional news outlets in China that have attempted to do real reporting in the face of formal press restrictions from the Chinese Communist Party leadership above, and frequent intimidation down below.

One post to WeChat and other platforms that shared images of the scuffle between the China Media Group crew and local police and other uniformed personnel bore the headline: "Finally, even the CCTV Reporter is Thrown Off the News Story."

Some noted that the intimidation and abuse of journalists from more professional outlets like those in Guangdong’s Nanfang Daily group — notable among them publications like Southern Weekly — has gone mostly unpunished for years. “There have been plenty of instances in recent years of journalists arrested and held in small black rooms, being searched and even beaten, all without causing any waves,” said one reflection from a social media public account called “Urban Land” which drew more than 13,000 comments on Netease alone.

“Local media are even subjected to online abuse if they openly report the ills they face,” said the post. “What they receive is not sympathy, but rather — oh, you Nanfang Group media . . . . this is what you deserve!”

The post suggested the incident in Yanjiao, on the outskirts of the small city of Langfang, was a further sign of a generally worsening situation for the press in China, saying it marked “a new phase” (一个新阶段) in which no media, including the generally obedient outlets directly under party-state control, are safe from intimidation and interference.

Former Southern Weekly journalist Chu Chaoxin (褚朝新) made the same case as he said the harassment of the CCTV reporters had brought a moment of unfortunate equalization. “This time in Langfang, we journalists are equal at last. Not equal in our freedom to access the scene for reporting, but equal in being denied reporting from the scene of the explosion," he wrote.

Dominating the Front Lines

As press controls have tightened over the past decade, it has become much harder for journalists, particularly those from less influential commercial outlets, to report breaking news from the scene.

Beginning under President Hu Jintao in 2008, reporting by central state media of “sudden-breaking incidents,” or tufa shijian (突发事件), was encouraged as a means of exercising tighter control of sensitive news reporting. The idea, coming under Hu's notion of "public opinion channeling" (舆论引导) was to ensure state media could fill information vacuums with "authoritative" reporting to prevent destabilizing public speculation. Meanwhile, regional and commercial newspapers and magazines — which in the proceeding decade had earned a reputation for often doing more free-wheeling coverage — could be held back from the scene of breaking stories with explicit orders and bans. This avoided coverage into deeper into questions of responsibility, what propaganda authorities often call "reflecting back."

Despite the leadership's attempts to rein in more open reporting of sudden-breaking incidents, professionally-minded outlets continued to push the bounds into the early 2010s. The Wenzhou train collision in the summer of 2011 was one of several outstanding cases that underscored the limits of Hu Jintao's vision of responsive press control.

Those limitations all but evaporated after 2013, as Xi Jinping boldly reasserted control over the press and social media platforms, even going so far as to explicitly ban the promotion of "the West's view of journalism" in a communiqué that year that came to be known as "Document 9."

The complete dominance of official media reporting in the wake of the Oriental Star tragedy in June 2015, in which a tour boat capsized on the Yangtze River, killing more than 400 people, was a graphic illustration of the silencing of China's professional press on sudden-breaking stories. Front pages in usually more outspoken papers carried identical content, images and layouts to Party-run newspapers, all drawing on official news releases, or tonggao (通稿), from the state-run Xinhua News Agency.

Xi Jinping offered an even more direct and robust vision of CCP control of the media in February 2016, as he visited the offices of the People's Daily newspaper and CCTV and stated that media must "love the Party, serve the Party and act for the Party."

It's Official: Local Governments Control the News

It is generally observed, and broadly true, that Xi Jinping now exercises much tighter control over the reins of power in China. He has tightened the CCP's control of the government. He has tightened the Party's control over the country's financial system. But when it comes to news and information, the tightening process has resulted in a dangerous devolution to local governments.

This may be the most important lesson to draw from yesterday's kerfuffle on live television.

For years, the process of reporting every manner of news story at the local level — from the country and city up to the province — has come to be highly concentrated with local authorities and their information operations, precisely because media have been neutered from the top down to the bottom. The situation is worsened by the fact that Xi Jinping has emphasized the power of Party institutions and modeled a strong-arm approach to governance. Local authorities have almost certainly been further emboldened by the extended exercise in strict social and political control afforded by Xi's "zero Covid" lockdowns.

In today's China, the release of news and information has come to rely more than ever on a growing official ecosystem of public accounts operated by local authorities, from city police departments to provincial information offices. As a result, the local authorities with the most to gain from suppression of the truth are nearly always the primary source of information that is then dutifully repeated and disseminated by party-state media through official news releases, as "authoritative."

Much of the debate over the pushing and shoving yesterday in Hebei has centered on the question of "reporting." But it is hardly an exaggeration to say that real reporting in such cases is frighteningly scarce anywhere in China in recent years.

The Yanjiao explosion has thus far been no exception. Reports on the incident this morning on major news websites relied on central state media releases that were themselves entirely reliant on information provided by local “relevant departments” (有关部门) — and made little or no apparent effort to speak to other sources on the ground. A report on the Chinese-language website of the Global Times, sourced from CCTV, revealed only that an explosion had occurred in the town of Yanjiao in Sanhe at 7:54 PM on March 13, caused by a gas leak, and that it had so far killed 7 and injured 27, with 14 already released from hospital. Site cleanup and investigation, it added, were ongoing.

When it comes to news and information, the process of tightening has resulted in a dangerous process of devolution to local governments.

An official news release this morning from China's official Xinhua News Agency relied solely again on information released from emergency response authorities in Sanhe, noting after repeating the same details included in the CCTV/Global Times missive, that "the cause of the accident is under investigation." A nearly identical report in English was also released by Xinhua early this morning. (For more insight into the dangers of the news release system and the loss of professional reporting, see our 2022 report "Mystery Kills" about how false rumors of the pending arrest of Alibaba founder Jack Ma sent shares tumbling 10 percent in Hong Kong.)

The dearth of real reporting on the explosion in Yanjiao, a revealing counterpoint to the outrage over the harassment of a reporter on the scene, brings us to the next twist in the CCTV story — the initial response given by the All-China Journalists Association (中华全国新闻工作者协会), or ACJA.

Rights, and Wrongs

Though the ACJA is ostensibly a professional association representing the media sector in China, it is a Party-affiliated organization overseen by the Central Propaganda Department, and its Charter commits it primarily to such political demands as "adhering to and strengthening of the overall leadership of the Party." Rarely in the past has the ACJA — which also plays a critical role in training and licensing reporters as adherents to Party control under the auspices of the "Marxist View of Journalism" — come to the defense of working journalists.

But as the CCTV incident broke on the internet late Wednesday, the ACJA became the unlikeliest of dissenting voices on the rights of journalists.

In a statement posted sometime after 9 PM, the association was unusually direct and stern, saying that the authorities must not, in the interest of controlling public opinion, "simply and brutally obstruct media reporters from performing their normal duties." "If the video circulating online is authentic, we raise three questions," the ACJA statement read after a rundown of the situation based on the video circulating online.

To the first question, "Should journalists engage in reporting?" the statement responded in uncharacteristically concise language:

They should. In the case of such a major public safety incident, the public looks forward to knowing more information. Journalists use their professional lenses to record the actual situation of the disaster and the rescue process, responding to public concerns and stopping the spread of rumors to the greatest extent possible.

To the second question, "Was the journalist adding to the confusion?"

They were not. When journalists report truthfully on the situation at the scene, reporting calmly, professionally and objectively, abiding by the ethical code of journalism, this can maximize the relief of public anxiety and protect the people's right to know.

In both of these responses, the emphasis was not just on professionalism but on the public's right to know (知情权), a concept that has been seen only rarely in the official discourse in recent years — and that has appeared just once on the ACJA's website over the past year.

It was the third question, however, that was most provocative. It touched on the nature of the Party-led news system and its reliance on the authoritative release: "Can official news releases truly replace live reporting?"

They cannot. If there were no media reporters, how could the public find answers? The first way would be to look at official releases, and the second would be to look at a wide array of information circulating on the internet. However, the official release will not be all-inclusive, and the information on the internet might breed rumors, so it is important for the media to supplement information.

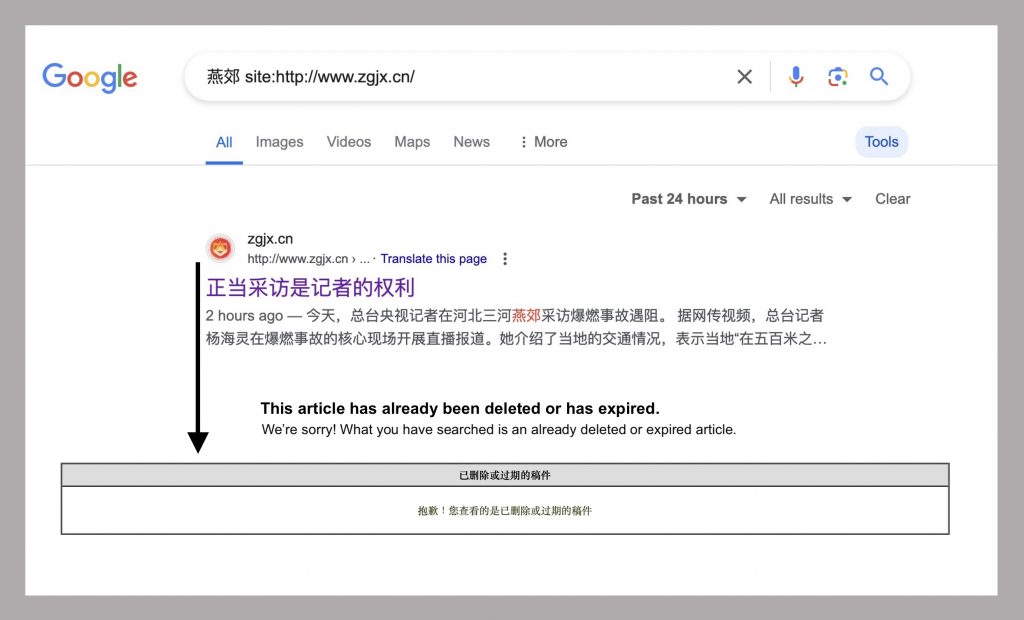

Adding mystery and inconsistency to the drama, the ACJA statement was removed at some point today from the association's website (above), even as it remained available on its WeChat account. But the statement has already touched — wittingly, or not? — on the core issue facing journalists in China today and their relationship to the public and its right to know.

That issue, the obstruction of the news by those in power, has now been dramatized on national television in the case of the Yanjiao explosion. But as professional journalists have known painfully for years, and as CCTV reporters should know better than most, having pledged their allegiance to Xi Jinping and the Party in dramatic form almost exactly eight years ago, that obstruction is not an aberration — it is policy.