On March 4 this year, just as China’s annual legislative meetings were set to open, the government surprised journalists with the decision to scrap the annual news conference with the premier, ending a practice in place for three decades. For most, this change was yet another sign of China’s inward turn.

A press conference with the foreign minister three days later finally gave the international press an opportunity for a face-to-face, and Wang Yi (王毅) seemed eager to appear open and off-the-cuff. As the spotlight fell on Ameen Muneer Mohammed Al-Obaidi, a reporter with the Dubai-based China-Arab TV, the foreign minister became jocular: “Are you the young man who performed the kemusan dance [online]?” he beamed, referencing a freestyle street dance that had gone viral on China’s internet the previous year. Al-Obaidi, who is Iraqi, then lobbed a softball question that referenced China’s external propaganda policies. “What role can foreign reporters play in telling China’s story well?” he asked in faultless Chinese.

This exchange, no doubt intended to appear unscripted, highlights how fundamentally China has shifted the game in recent years to advance its state narrative. For starters, it has expelled experienced foreign correspondents and made visa approvals difficult; it has stacked the deck at government events with compliant guest reporters on government-run journalism exchanges. The Al-Obaidi case is likely something different altogether — the creation of a completely cloaked regional media group abroad that can further China’s state propaganda goals, no questions asked.

For several days after Wang Yi’s smiling exchange at the National People’s Congress (NPC) with Al-Obaidi, who is also known as Fang Haoming (方浩明), state media continued to relish the moment. They remarked the level of interest “foreign journalist Fang Haoming” had shown in “telling China’s story,” a phrase now synonymous with the soft power goals of the Chinese Communist Party.

For our team at the China Media Project, the affectionate exchange between Wang and Al-Obaidi prompted a simple question: Who is China-Arab TV? Over several weeks, that question took us through a labyrinth of companies and personalities. We found compelling evidence to suggest that this friendly voice in the Middle East, a long time in the making, has more than a cordial relationship with the Chinese party-state and its foreign affairs ministry.

The Brothers Liu

China-Arab TV (中阿卫视), or CATV for short, which on its Facebook page calls itself “the first and only Sino-Arabic satellite television channel in the Middle East,” was the brain-child of two brothers. The elder, Liu Haitao (刘海涛), arrived in Dubai in 1993 to explore new business opportunities. For a time his focus was on Chinese restaurants in the city, but before long he had connected with a “shrewd” and like-minded businessman Wang Weisheng (王伟胜), whose interests ranged from real estate to footwear and bedding. On the board of a local Chinese business association, Wang was at the center of a growing Chinese expatriate community in Dubai. In 1999, the year after his arrival, he and Liu Haitao set up “Dubai Chinese Info Online” (迪拜华人信息网), a free listings website to connect Chinese and Arab businesses, which made them “celebrities” in the Dubai Chinese community, according to a later profile.

In 2006, the two men established Alibaba Business TV (阿里巴巴商务卫视), which focused on product sales across the Middle East. The investment made sense given the growing trade relationship between China and the region, even though the two had, by their own admission, a “limited understanding” of the media industry beyond their online listings venture. The company had no relationship with China’s Alibaba Group. By this time also, Liu Haitao’s younger brother, Liu Haijiang (刘海江), had followed him to Dubai.

At this early stage, Chinese state media showed an interest in Liu and Wang’s network only insofar as it could showcase China’s growing economic ties with the UAE. But that changed in 2013, as Xi Jinping outlined in August that year a bold new vision for foreign propaganda work that would urge Chinese media and official entities across the country to join in “telling China’s story well” on the global stage. This was followed closely by the launch of Xi’s massive signature infrastructure development project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Both initiatives sharpened China’s focus on partnerships in the Global South, including the Middle East. For Liu Haitao, who now had seven years’ experience operating a TV station in Dubai, this must have seemed a moment of near-perfect alignment between his business interests and China’s international goals.

Right Place, Right Time

On July 20, 2014, less than a month after Xi Jinping’s announcement that China would deepen cooperation with Arab states in oil and gas, infrastructure, trade and investment, and other areas under BRI, the Liu brothers enlisted Sheik Majid, an Emirati royal, to found China-Arab TV. The network was registered under the economic license of Arab Business TV FZ-LLC.

From the outset, they described their network as positioned at the intersection of state and commercial interests. In an interview with Home Voice (鄉音), a Chinese diaspora outlet based in New Zealand, Liu Haijiang stressed that overseas Chinese media like CATV must seek business success by serving the BRI and following Beijing’s latest directives. “The development of overseas Chinese media,” said Liu, “is inseparable from China itself.”

Was there more direct involvement at this early stage from the Chinese government? This is unclear. But a terse post in Chinese to CATV’s website, dated to late 2014 and preserved in online archives, offers a tantalizing clue. According to the post, the network was registered in Dubai “under the support of the Chinese and UAE governments.”

Was there more direct involvement at this early stage from the Chinese government? This is unclear.

Like the Liu brother’s old Alibaba channel, CATV continued to promote products for Chinese enterprises in the Middle East. But by this time it was also clear that the Chinese leadership’s interest in exploring new forms of international communication was offering the network new opportunities.

Within six months of its founding, CATV had signed a strategic partnership agreement with the China International Communication Center (五洲传播中心), or CICC, an organization directly under the Information Office of the State Council, which handles the government’s external communication strategy and overlaps with the Party’s Central Propaganda Department. According to the partnership, the two sides would strengthen cooperation in film and TV production in order to “transmit China’s voice” and “promote China’s image among Arab countries.” This would also mean, according to state media coverage of the deal, advocating for Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative.

In a report on the deal in the entertainment section of People’s Daily Online, business and patriotic duty seemed to swirl together as company executives offered their felicitations. Jing Shuiqing (井水清), CICC’s vice-president, stressed the diplomatic advantages for the Chinese state — how the deal would work for the “foreign transmission of Chinese culture” and “telling China’s story.” Liu Haitao emphasized the huge trade opportunities opening up between China and Arab countries.

How lucrative was this deal for China-Arab TV? No related information is publicly available. But CICC is one of China’s most globally active official media organizations, with massive state resources at its disposal. Among its longstanding partners is the Discovery Channel, which has globally distributed CICC-backed programming that clearly tows the official line of China’s government on issues like Xinjiang, and has recently drawn scrutiny from members of the US Congress.

Whatever the arrangement, this was just the beginning of CATV’s dealings with powerful CCP-linked media groups that were now under a strong mandate to venture forth and find new ways to reach foreign audiences.

Future collaborations, however, would be spearheaded by new corporate leadership.

Enter Zhang Lijun

In August 2016, Hong Kong’s publicly listed V1 Group — which trades today as Crazy Sports (0082 HK) — made a strategic investment in the Arab television network launched almost exactly two years earlier by the Liu brothers, purchasing more than three-quarters of the company’s shares.

V1, which was named in financial media at the time as a “Beijing-based Internet video producer and mobile-phone lottery company,” sought a partnership, according to a company press release, that would help it pursue a media convergence strategy called “Internet Plus TV,” a name that referenced the “Internet Plus” strategy unveiled the previous year in the government work report from Premier Li Keqiang. Prior to its majority purchase of CATV, the V1 group had placed the State Council’s guiding opinion on “Internet Plus” at the core of its strategic planning, making it “a key business of the Group.” Together, V1 and CATV would advance these goals and create a media platform to “accelerate cultural exchanges and economic and trade cooperation between China and Arab countries,” said the release.

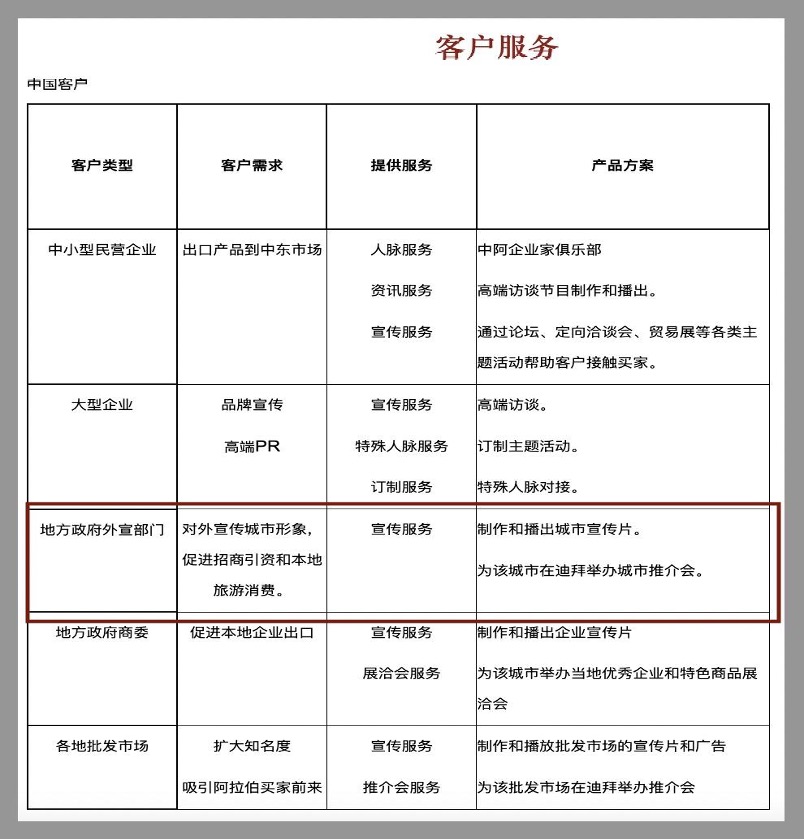

Within a year of the V1 share purchase, the network was also offering a range of client services to Chinese companies and local governments capitalizing on its position as a media player in the Middle East. For local government propaganda offices in China, for example, its services included “external image publicity,” which involved the production and broadcast of promotional films for cities.

We need not imagine such services in practice. As Al-Obaidi rode the wave of official news coverage after the NPC press conference with Wang Yi in March, “Hola Fujian,” a foreign communication platform operated by the CCP leadership in the province, wrote on its X account that the Arab journalist had “deep connections with the Fujian Media Group,” which had collaborated with China-Arab TV on a series of promotional short videos called “Ameen’s Fujian Time.” Directed at Arab audiences, the series aired in late March on China-Arab TV and was shared across its accounts on Facebook, YouTube and TikTok.

The ambitions of executives at V1 at the time of the purchase in 2016 went beyond such government-backed promotional schemes — and those ambitions were embodied in the person of V1 CEO Zhang Lijun (张力军).

In comparison to the relatively low-profile Liu brothers, Zhang Lijun, who became the new boss at China-Arab TV, was a mover and shaker. He positioned himself as an innovator and business ambassador, a champion of “disruptive innovation.” Among the many hats he wore, Zhang was an honorary chairman of the Bank of Asia (亚洲银行), a cross-border financial services provider based in the British Virgin Islands that serves “high net worth China-based and other Asia-based customers,” and in which V1 Group was an early investor. Another co-founder of the Bank of Asia — which, to be more frank, helps Chinese businesses register in offshore jurisdictions — is Carson Wen (溫嘉旋), a prominent member of Hong Kong’s leading pro-Beijing political party, the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), and a three-time deputy representative for the city to China’s National People’s Congress.

Public coverage of Zhang Lijun suggests a savvy networker in diplomatic circles as much as business ones. In 2002, he became chairman of the China APEC Development Council (中国APEC发展理事会), an organization ”guided” by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and designated by the ministry in 2004 as “a working organization to promote China’s participation in the APEC development process through a mechanism of combining government, industry and academia.” APEC, or Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, is an intergovernmental forum promoting free trade among 21 member economies in the Asia-Pacific.

Within a year of the V1 share purchase, the network was also offering a range of client services to Chinese companies and local governments.

This close MFA connection with the China APEC Development Council is worth bearing in mind given the exchange between Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Ameen Al-Obaidi that began this story. A curious fact of unknown significance is that the APEC Development website directs queries to an address at V1 Group.

Whatever the relationship, Zhang’s APEC title put him right at the center of trade and diplomacy. And this was by no means his only appellation. The V1 CEO was also an advisor to the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office (国务院侨务办公室) of the State Council, the external moniker used by the CCP’s United Front Work Department (UFWD) — which coordinates many of China’s influence operations globally, including within diaspora communities. He was a governing member of the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (海峡两岸关系协会), or ARATS, an organization directly under the Taiwan Affairs Office of China’s State Council.

Zhang’s APEC role also placed him in close proximity with global leaders. Over the years, he managed to collect photos of himself with a parade of presidents and premiers, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, and US presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

Like many PRC business executives, Zhang was also adept, when necessary, at code-switching from business talk to the specialized jargon of China’s party-state. At times, the V1 CEO sounded the part of the Party politician.

In 2018, for example, two years after the purchase, Zhang laid emphasis not on business or even media as CATV opened a news center in the Chinese capital. The CATV center, he said, was helping China realize its Second Centennial Goal, referring to the building of a “modernized and powerful” country by 2021 — one hundred years, that is, since the founding of the Chinese Communist Party.

Such mixing of priorities was evident even at the time of the V1 takeover, in ways that might have perplexed investors in the Hong Kong-listed entity.

At the press briefing announcing the acquisition, Zhang said CATV dovetailed with V1’s aspirations to serve as “an important foreign propaganda platform for China.” He painted in the broad strokes of state media and trade policy — with phrases about “implementing [the] media integration strategy” (媒体融合战略), “changing lanes to overtake” competitor nations (换道超车), and, of course, promoting the BRI. Shortly after, echoing Xi Jinping, he said that the main responsibility of media outlets was to “tell China’s story well.”

In China, it is not unusual for politics to go hand-in-hand with profit making. But another knock-on effect of the sale of China-Arab TV to a Hong Kong listed company was that the finances of the network became public. They raise further questions about the motivations behind the purchase.

As the V1 Group took over CATV, the network was already in financial straits, according to early filings under V1. Losses deepened after the takeover, increasing threefold between 2016 and 2017. In August 2016, V1 signed a “service agreement” with one of the brothers, Liu Haijiang, to stay on as director of CATV and deliver a profit by the end of 2018 — or else forfeit his shares. Perhaps the task was too much for Liu, or perhaps the spell of “love at first sight” he reportedly experienced with Zhang had begun to wear off. Whatever the facts behind the scenes, the CATV founder had formally resigned as a CATV director by the end of 2017, with no profit in sight. From that point on, Liu’s role in the network is unclear. He reemerged briefly to attend the opening of CATV’s Beijing news center on January 31, 2018, an occasion curiously anticipated by the setup in Hong Kong of a lone entity called Dubai China Arab TV (迪拜中阿衛視), of which Liu was the only listed director and shareholder through to its folding five years later.

So far as can be ascertained through publicly available documents, CATV remained a consistent loss maker for the V1 Group.

Cozy Connections

Even as the commercial prospects of V1’s China-Arab TV dimmed in public disclosures, its political horizons brightened. In 2018, just two years after the takeover, the network struck an agreement with the recently-formed CCP mega-conglomerate China Media Group (CMG). According to the agreement, CATV would dub and broadcast Chinese television programming in the Middle East.

The China Media Group deal, unveiled in Dubai, was a major diplomatic affair for China and the UAE. The marquis event was attended by Wang Xiaohui (王晓晖), the executive deputy head of the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department as well as senior Chinese diplomats. The official host was the Information Office of the State Council, once again driving home the opaque distinction between the CCP’s powerful media control body and the government office responsible for China’s international communications.

After two years with Zhang Lijun at the helm, CATV remained unprofitable, according to V1 filings. But the network was swimming with the biggest fish in China’s state-controlled media pond. Its partners, according to filings with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, included the aforementioned CICC; the state-run broadcaster and CMG subsidiary China Central Television (CCTV); the official newswire Xinhua News Agency; the country’s number-two newswire, China News Service, led by the CCP’s United Front Work Department; and local government-run networks like Ningxia TV.

After two years with Zhang Lijun at the helm, CATV remained unprofitable.

CATV was now actively pursuing, as Zhang had explained early on in his involvement, “intensive cooperation with Chinese mainstream media” — this being a buzzword in the Chinese context for CCP-run media meant to lead the public agenda.

Given this positioning of China-Arab TV’s interests, it was simply a matter of business that the network’s agenda should match that of China’s leadership. According to V1’s 2016 Annual Report, one of CATV’s arrangements under its deal with the propaganda department-linked CICC was for production of a documentary supporting China’s claims to contested areas of the South China Sea.

This production work was timely. On July 12, 2016, an arbitral tribunal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea adjudicated a case brought by the Philippines against China in the South China Sea, and ruled overwhelmingly in favor of the Philippines. The tribunal deemed that key elements of China’s territorial claims in the highly-contested region were illegal, including its land reclamation efforts. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs fumed. Within weeks, China-Arab TV, newly in the hands of V1, was working with the CICC to produce a state-backed documentary mirroring China’s foreign policy to its audience in the Middle East.

At this point in the story, China’s strategic interest in the UAE-based broadcaster — evidenced in the line-up of state media partners — should be apparent. Positioned in the Middle East, China-Arab TV could reach audiences in the region at a time when the CCP leadership was doubling down on its efforts to strengthen China’s presence in foreign public opinion. And in fact, this pivot was one of Zhang Lijun’s first orders of business as CATV chairman following the V1 buyout.

According to the V1 Group’s 2018 annual report, Zhang led the strategic decision to focus CATV on Arabic audiences in the Middle East. This was a departure from the channel's target audience under the Liu brothers, who had prioritized overseas Chinese — particularly those engaged in trade in the region. After 2018, CATV’s languages were Chinese and Arabic, and English was dropped.

Soon, passengers shuttling between China and the Middle East on the national flagship carrier Air China could watch CATV programs, including state-funded content from CICC and the China Media Group, in either Chinese or Arabic. That programming included news dispatches from Ameen Al-Obaidi’s predecessor as celebrity reporter at CATV, the Egyptian anchor Hoda Alaa (馨玥) — referred to with seasonal sexism in China’s state media as the “beautiful Arab female journalist,” and “the spice girl” for her dashing red outfits.

Like Al-Obaidi, Alaa rode waves of publicity in Chinese state media around major political events — including the CCP’s 19th National Congress in 2017, where she too was handed a rare opportunity for a question at the official press conference. Alaa’s presence at this and other events, such as Beijing’s Conference on Dialogue of Asian Civilizations in 2019, was an opportunity for outlets like the government’s own China Daily to demonstrate the friendly and non-confrontational posture expected of journalists for foreign media.

By March of last year, when newly-minted CATV correspondent Al-Obaidi had his first opportunity to question a senior Chinese official — the soon-to-vanish Foreign Minister Qin Gang (秦刚) — the UAE-based network had settled into a rhythm as a friendly foreign outlet with privileged access. For state media, Al-Obaidi was the quintessential “foreign media representative,” stressing in conspicuous CCP jargon the need for international journalists to report “a more multifaceted China.”

But more than this, he epitomized the “lovable” (可爱) presentation of China to the world that Xi Jinping had strategically outlined for foreign propaganda during a related session of the CCP’s Politburo in May 2021. What could be cuter than the country’s foreign minister and a foreign reporter sharing a moment about a viral dance routine?

The network’s close collaboration with central state media and provincial government propaganda departments notwithstanding, China-Arab TV’s real connections to China have remained opaque. To what extent was the intimacy between Al-Obaidi and Foreign Minister Wang Yi friendly and sympathetic, and to what extent might it be familial? How, in other words, does this Dubai-based media outlet connect?

The Journey East

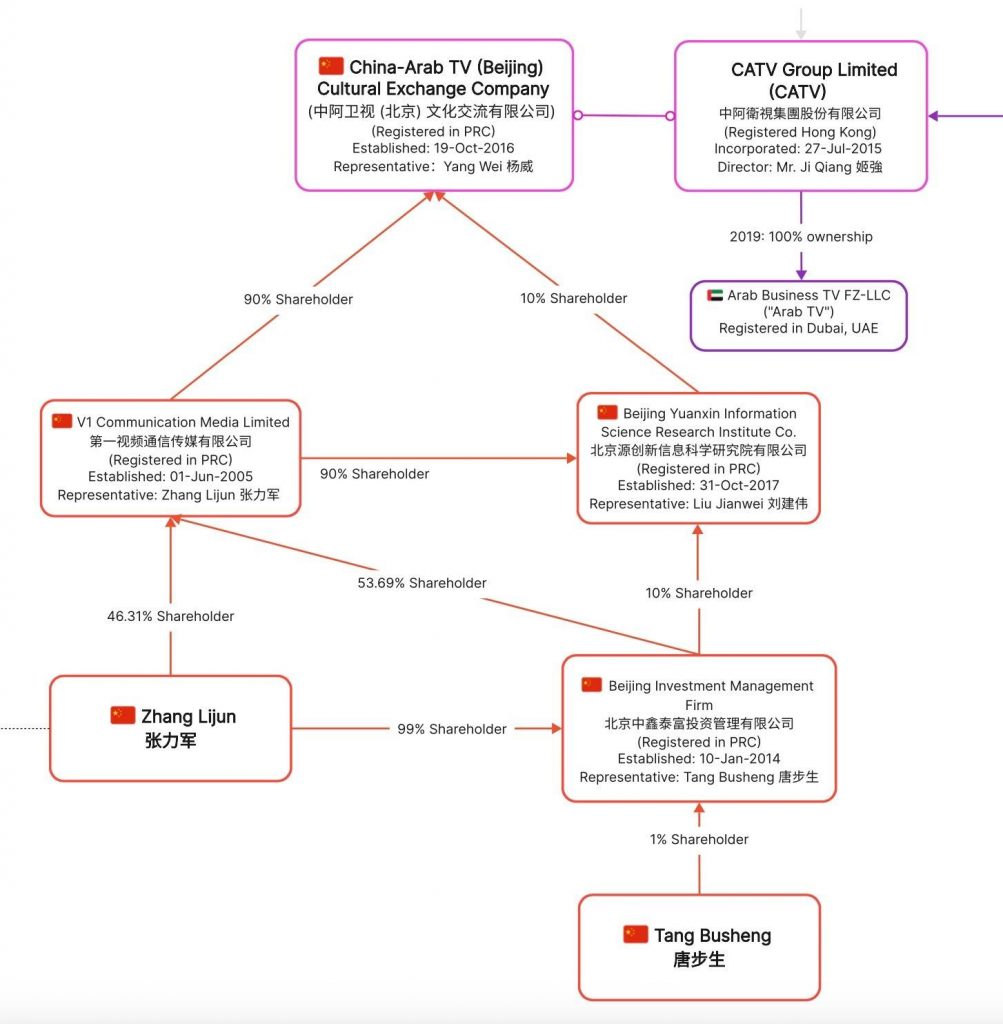

The UAE’s discernibly China-friendly China-Arab TV remains in the hands of Zhang Lijun today. But closer scrutiny of the network’s corporate structure is a mystifying journey across geographies. The path zigzags from Dubai to the British Virgin Islands, to Hong Kong — and on to Beijing.

The clearest views of the landscape of China-Arab TV can be found in corporate registration records in Hong Kong, the home of the V1 Group (now Crazy Sports) — and across the border in China.

On the Hong Kong side, CATV is registered as CATV Group Limited, a company incorporated in July 2015, one year before the announcement of the V1 takeover. Between 2016 and 2019, the Hong Kong company’s stake in Arab Business TV FZ-LLC, the Dubai-based license holder, ballooned to 100 percent.

Where does the road to China lead?

The first stop on the China side is China-Arab TV (Beijing) Cultural Exchange Company, which is 90 percent held by Beijing-based V1 Communication Media Limited — its representative being the familiar Zhang Lijun. Zhang directly holds just over 46 percent of V1 Communication Media. All other shares are held by a separate company, Beijing Investment Management Limited, in which Zhang Lijun owns 99 percent. Holding the final one percent, giving him a sliver of China-Arab TV (Beijing), is Tang Busheng (唐步生), whose story is at least as colorful as that of his business partner.

The path zigzags from Dubai to the British Virgin Islands, to Hong Kong — and on to Beijing.

Like Zhang Lijun, Tang Busheng is a key figure in the China APEC Development Council, the APEC engagement mechanism “guided” by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). Zhang is chairman and Tang secretary-general of the group. Also linked to the group — and not at all incidentally — is Yang Wei (杨威), the registered representative of China-Arab TV (Beijing) Cultural Exchange, the first company in the China-side chain. Yang has served as deputy secretary-general of the APEC Development Council, and according to his LinkedIn profile, has been CATV station chief since the departure in 2018 of network co-founder Liu Haijiang. Before that, however, Yang was Section Chief Yang, working as a mid-level official within the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department. Immediately prior to that on his resume is a five-year stint at the State Council Information Office, which, as Chinese foreign policy expert Anne-Marie Brady writes, “oversees the country’s external propaganda, guiding the foreign-propaganda activities of the multiple government offices whose portfolios touch on foreign matters.”

Given the association of all core China-side partners in China-Arab TV with the APEC Development Council, it seems probable the organization plays a crucial intermediary role for its “guiding” institution, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. That probability increases exponentially when one considers that China-Arab TV’s current station chief formerly worked at the heart of the party-state’s external propaganda apparatus. Remember: the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department and the State Council Information Office, where Yang Wei spent a combined 18 years, are in fact a single office dealing with foreign propaganda, and working, just as Brady has indicated, in close concert with China’s MFA.

But the connections do not stop here.

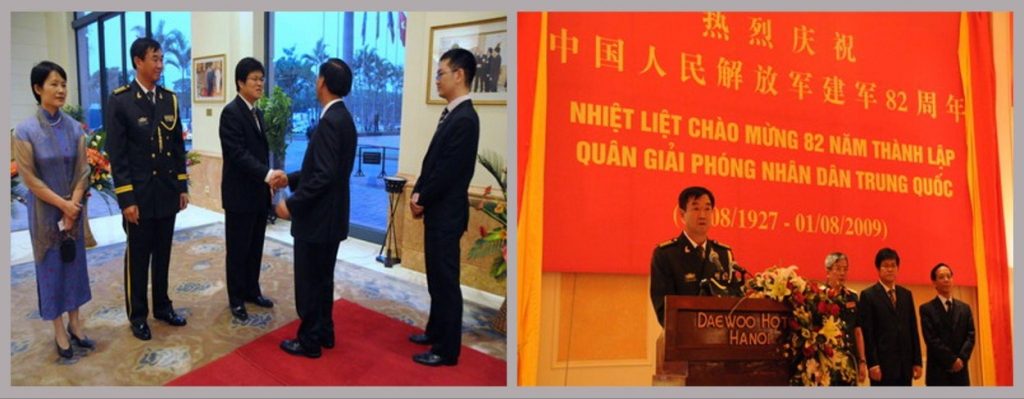

Returning to Tang Busheng — the holder of that sliver of China-Arab TV (Beijing) Cultural Exchange — there are fewer and less frequent details available than for his conspicuous counterpart, Zhang Lijun. Digging deep into online archives, however, it is clear that before he took his more recent soft turn into the world of broadcast media, Tang was involved on the security side of China’s foreign diplomacy. With the rank of major in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), Tang served more than a decade ago as China’s military attaché for land, air and sea forces at the Chinese Embassy in Vietnam. He is pictured meeting with senior Vietnamese officials in Hanoi in July 2009, and in 2010 played host in Saigon to one of China’s most senior generals, Ma Xiaotian (马晓天), then commander of the PLA Air Force — who famously sparred at the Shangri-La Dialogue that year with US Defense Secretary Robert Gates.

Tang Busheng worked previously in Chinese embassies in the United States, Denmark and the United Kingdom. He was also, according to his China APEC Development Council profile, a United Nations military observer for China to Iraq and Kuwait. More recently, in December 2018, Tang was pictured in his capacity as secretary-general of the China APEC Development Council alongside V1 Group Chairman Zhang Lijun in Silicon Valley, where he attended the formal launch of a V1 branch in the United States called Vland Inc.

Beyond the connections outlined above, both of these men have leaned more than casually into their political allegiance to China’s ruling Party and its propaganda objectives. Just two weeks before their Silicon Valley trip, the two men were together in Beijing for a V1 Group meeting, where Zhang Lijun was introduced as the group’s “Secretary of the CCP Committee.” In his address to the gathering, Zhang stressed the need to study and submit to the media control policies of the CCP leadership, including enforcement of strict “public opinion guidance.” Party-run media, said Zhang, must maintain “a high level of unity with the Party, and only then can [China] respond to international competition and challenges.” Tang Busheng, identified in the report as V1’s “external liaison director,” another title with oddly political cadences for a listed company, echoed these cautions. "It is important that as media we are responsible, adhering to correct public opinion guidance and continuing to transmit positive energy,” he said, “even as we ensure readability, interest and originality.”

It is not unusual for private company executives operating in the sensitive sector of the media in China to pay lip service to the control priorities of the party-state — and even at times to grovel to signal compliance. However, it is exceptionally odd for the executive of a Hong Kong-listed company with media interests grounded in foreign markets to suggest that his outlets are “Party-run media” (党办媒体), a phrase referring specifically to media directly under the thumb of the party-state.

The link between the V1 Group and the APEC Development Council, with its clear yet inconclusive dotted line to China’s MFA, offers a tantalizing clue to how China-Arab TV might connect. But for all the transparency required of a publicly listed company, the V1 Group is its own enigma, and the financial attractiveness of the group’s investment in the loss-making CATV is difficult to fathom.

The Crazy Sport of CATV Finances

First launched in 1991 as Yanion International Holdings, the V1 Group underwent a series of name changes over two decades before landing on today’s Hong Kong-listed Crazy Sports Group Limited (0082 HK), which identifies itself as “a leading digital sports entertainment community operator and internet sports industry leader in China.” The name “Crazy Sports,” used after 2021, reflected the V1 Group’s pivot toward what Zhang Lijun called at the time “China's trillion-yuan sports industry.”

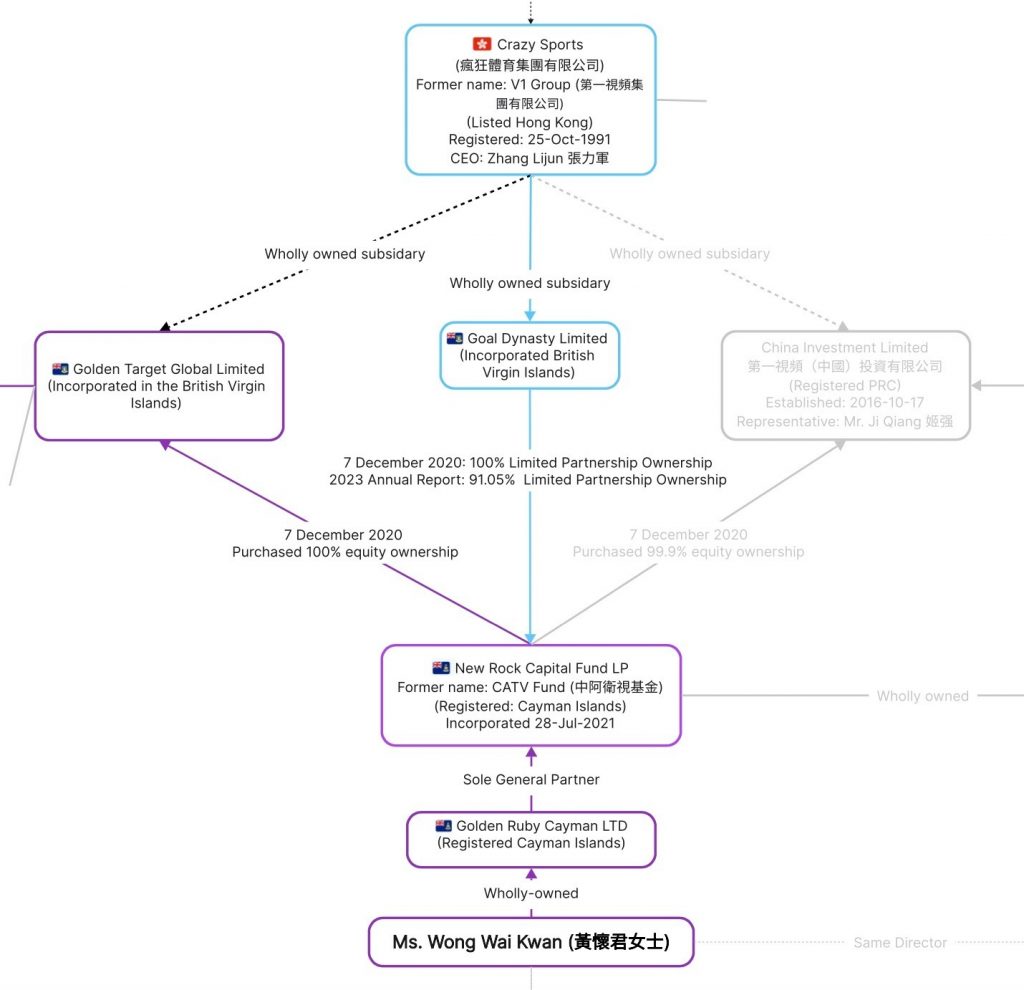

Understanding the link today between Crazy Sports and the China-Arab TV that had its lovable exchange with China’s foreign minister back in March takes us to the offshore side of our sprawling map of CATV.

Until the end of 2020, the network’s holding company in Hong Kong, CATV Group Limited, was held by the V1 Group through an investment vehicle in the British Virgin Islands called Golden Target Global Limited, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the V1 Group, according to a Hong Kong filing. In the midst of a restructuring on December 7, 2020, the shares held by Golden Target Global, were sold off to an entity in the Cayman Islands called the CATV Fund (now known as New Rock Capital) for 11.08 million US dollars. In Hong Kong filings, V1 later explained that holding on to CATV had become too “capital intensive.”

And yet, the same day, in a hand-switch move that effectively put CATV finances held by the V1 Group beyond the reach of Hong Kong disclosure requirements, the V1 Group subscribed to the CATV Fund (New Rock Capital) for an identical investment of 11.08 million through Goal Dynasty Limited, another wholly-owned subsidiary in the British Virgin Islands. Despite the language about the “capital intensive” nature of V1 Group’s holdings in China-Arab TV, in other words, the group turned right around and provided a seed investment in the network’s new offshore owner in an amount equivalent to its divestment.

Recent filings by Crazy Sports in Hong Kong are clear about its continued interest and involvement in China-Arab TV, which it holds through a 91.05 percent equity investment in BVI’s Goal Dynasty Limited, making it the majority shareholder in the limited partnership arranged through the December 2020 restructuring. Records released last year lay out Crazy Sports’ continued multi-million dollar investments in the CATV Fund (New Rock Capital), including more than 16 million US dollars in 2022.

The 2020 restructuring did nothing to change Zhang Lijun’s status as the most visible executive at China-Arab TV, and the businessman continues to identify himself as the “Chairman of Dubai’s CATV.” But it did cast a new layer of obscurity over the question of who is behind China’s voice in the Middle East. The entity operating China-Arab TV today, the Cayman-based New Rock Capital (CATV Fund), is a limited partnership, which means that operations — including those of China-Arab TV — are managed by the general partner in return for a management fee and a share in any profit. As public filings make clear, the CATV Fund (New Rock Capital) was created in the restructuring to “achieve long-term capital appreciation” by leveraging the “external network” and “expertise” of the general partner.

So the all-important question: who is the general partner?

CLICK HERE for the full corporate structure of China-Arab TV.

The trail from the CATV Fund (New Rock Capital) leads on through another Cayman-registered entity tantalizingly called Golden Ruby, and thence on to a single name: Ms. Wong Wai Kwan (黃懷君). Public filings by the V1 Group in 2020 claim that Ms. Wong is an expert in running telecommunication and media businesses, which might reassure shareholders in the listed company that their investments are in good hands. Despite Ms. Wong’s vaunted expertise and apparent importance to the ongoing CATV venture, however, she is a complete mystery. She has left no digital footprint, a feat nearly inconceivable for a woman who, according to V1 filings, controls a company that "invested approximately US$200 million in a PRC mobile games company and made a remarkable return on the investment."

In the end, the trail that began with a television studio in Dubai ends with an unknown quantity. Who is Wong Wai Kwan? And why is this question so important?

To answer this, we must return to the scene of this year’s National People’s Congress and the good-humored exchange between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and China-Arab TV reporter Ameen Al-Obaidi, which epitomizes China’s politics of media distraction. A moment that should have been an opportunity for serious questions directed to the foreign minister of the world’s second-largest economy, a hugely consequential player on the global stage, became instead a comic setup that spiraled into a state media love fest about Al-Obaidi and the kemusan dance.

At a time when citizens globally need integrity and truth from journalists and media, China’s leadership is not just becoming less open — but is working determinedly behind the scenes to obscure, soften and make “lovable” the entire question of its role in the world. In the case of China-Arab TV, the fact that our determined pursuit of transparency ends only with the baffling Ms. Wong and her Golden Ruby, glistening in the offshore murk, tells us that when it comes to China we might have a much more serious problem than not getting the answers — we may not even know who is asking the questions.