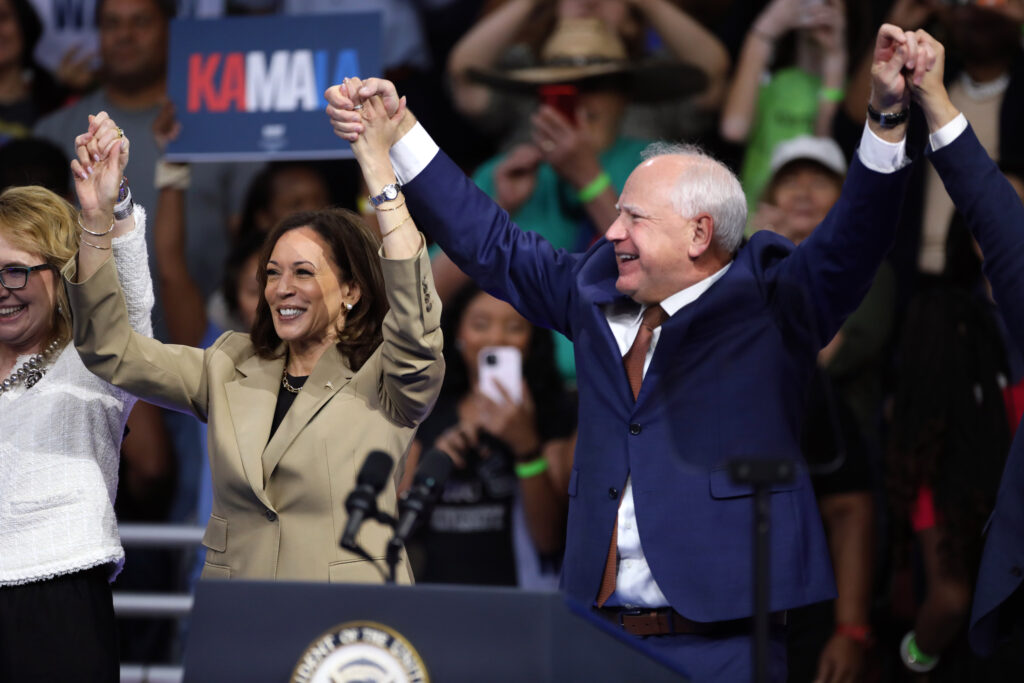

On August 6, the US Democratic Party’s presidential candidate Kamala Harris finally chose her running mate: the 60-year-old governor of Minnesota, Timothy Walz. Subsequently, the media discovered that Walz had lived in China in his younger years. From September 1989 to July 1990, he worked as a foreign teacher at Foshan No. 1 Middle School in Guangdong province.

In the context of recent Sino-US competition, and given the shift in the most recent administrations between the fierce confrontation of Trump and the competitive risk control approach of Biden, the vice-presidential candidate’s China experience has become a focus of attention both inside and outside China.

How does Walz understand China? What is his position on Sino-US relations? In this article, Initium Media looks closely at his teaching career in Guangdong and his engagement with Chinese society before and after 1990, as well as his involvement in related policy and legislative work once in politics.

Walz in Foshan: Learning Cantonese and winning the hearts of students

For more on Walz’s time teaching English in China, our reporter contacted Ms. Pang, a recently retired Chinese language teacher at Foshan No. 1 Middle School. Pang was a colleague of Walz’s, who she says was the school’s first foreign teacher.

At the time, Pang says, Walz was known to teachers and students as simply as “tīm” (添) — a Cantonese transliteration of his first name. Tīm was well-liked, according to Pang: “Everyone treated him like a celebrity,” she says. “He left a good impression on everyone. He was very young and had a bright smile… Even now when I see pictures of him I recognize that same wide, infectious smile pressing his cheeks up.”

After he returned to the US in 1990, Walz told his hometown paper that he got the “royal treatment” in the school’s dormitory — his room came fitted with air conditioning, a color TV, and a radio. He taught four classes a day on the English language and American culture, addressing about 65 students at a time.

Foshan No. 1 Middle School is considered a famous school locally. Founded as Wa Ying College (華英學校) by the Methodist Church of Great Britain in the early 20th century, the school re-established itself in British Hong Kong after the Communist takeover in the mainland. Over the past century, notable Wa Ying alumni — in Foshan or Hong Kong — have included Yellow River Cantata composer Sinn Sing Hoi (冼星海), reformist governor of Guangdong Ye Xuanping (葉選平), and Hong Kong-American economist Steven N. S. Cheung (張五常). Pang says that Walz took part in many activities at the school, and was the mainstay of the faculty basketball team.

In an interview at the time, Walz bemoaned the “unbearably hot” Guangdong weather but praised his students’ curiosity about all things American. At Christmas time, he said that students and friends decorated a pine tree and brought it to his room.

“His colleagues would often laugh at him because as soon as he got his pay he went to the school store to buy ice cream,” Pang recalls. Walz didn’t understand Cantonese or Mandarin when he first arrived, Pang says, but he gradually began to learn. Another old teacher at the school remembered how Walz bought a bag of lychees and invited him in Mandarin to share.

“Every time he spoke Cantonese everyone would applaud him,” a report from 1990 said, “but he said that learning Mandarin was very difficult.”

Initium Media also contacted Walz’s former students, but they said they couldn’t remember details of his classes after over 30 years. One former student said she only remembered that Walz gave all of his students English names — though she couldn’t remember what hers was.

After Waltz was announced as the Democratic vice presidential candidate, a retired Foshan No. 1 Middle School teacher shared a photo in a chat group of Walz traveling with his colleagues when he was a teacher in Foshan.

Friendly to Chinese, and long engaged in Sino-US civil exchanges

The start of large-scale American exchanges with the People’s Republic of China can be traced back to the end of the Cultural Revolution. After Deng Xiaoping took power, he promoted reform and opening. He sent a large number of Chinese students to the United States to study, and he welcomed American scholars and teachers to bring professional knowledge to China.

In 1978, Zhou Peiyuan (周培源), the then president of Peking University, led a delegation to Washington to discuss educational exchanges between China and the US. In October that year, the two countries signed an Understanding on the Exchange of Students and Scholars Between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China, opening the period of academic exchanges that has been called the “China-US Honeymoon.” The following year, after the normalization of US-China relations, teachers from American universities officially entered Chinese classrooms.

There were about 180 American teachers and 50 researchers living and teaching in China in 1981, according to a later study of memoirs written by American teachers in the country, and the number rose steadily from that point on.

In 1989, after serving in the Army National Guard and graduating with a bachelor’s in social science education from Chadron State College, Walz arranged to teach in China through Harvard University’s WorldTeach program. In his Congressional biography, Walz describes himself as “one of the first US educators to receive government approval to teach in China.”

According to a report by The Hill, Walz has said that he went to China because “China was coming.” After teaching for a year at Foshan No. 1 Middle School, Walz spent three months traveling across China, including at least six trips to the then-Portuguese colony of Macau, where he said he would eat McDonald’s and watch English-language movies. According to a 2007 financial disclosure statement for the US House of Representatives, Walz was a visiting fellow in international relations at Macao Polytechnic University.

In addition to visiting Macau, Walz traveled by train to Beijing, of which he once said: “It [Beijing] always brings back a lot of bitter memories.” Walz has said, however, that he never felt his safety threatened. Wherever he went, he could always ask students for assistance.

After his time in China, Walz returned to Nebraska and founded Educational Travel Adventures, a company that organizes annual summer educational trips for US students and provides scholarships for travel and study in China.

These activities are also remembered at Foshan No. 1 Middle School. “Four years later, he brought some people back with him, and I met him on campus again,” Mr. Pang said, referring to the 50 American students that Walz brought to China in 1994. “He was very attached to Foshan No. 1 Middle School, and he came back from such a faraway place and brought his girlfriend with him.” Mr. Pang was in fact referring to Gwen Whipple, also a school teacher, who had married Walz before the trip, on June 4, 1994. The trip to China with American students that summer was also a two-week honeymoon, including sightseeing, cultural study, and a bit of tai chi.

Walz on China: an emphasis on human rights and security, but support for dialogue

Walz, who taught in China and speaks some Chinese, is seen by many as having a more moderate China policy. Some Chinese netizens on Weibo hope that if he wins, he might give a boost to US-China relations. Critics such as former Richard Grenell, however, who served as Acting Director of National Intelligence (DNI) in the Trump administration, have criticized Walz for his record on China. “There is no one more pro-China than the Marxist Walz,” Grinnel wrote on X on August 6.

In terms of his political record, Waltz is far from a “dove” in his approach to China. He is a long-time supporter and advocate of political freedoms in China, and has criticized Beijing on issues ranging from Hong Kong to Tibet.

Both the 1989 student movement and the June 4 incident had a profound impact on Walz.

In a 1994 interview with Nebraska’s Star-Herald newspaper, Walz recalled that he, like all teachers in the WorldTeach program, had first received language training in Hong Kong in 1989. As he and other volunteers watched the news from Hong Kong on June 4, many decided to back out of the program. He had other ideas. “I felt it was more important than ever to go to China,” he said. He felt it was important, he recalled, for him to tell this story “so that the people of China knew that we stood with them.”

When he returned to the US in 1990, he remarked in an interview that the Chinese people he met were “all so kind, generous, and capable,” and that they simply lacked “the leadership they deserved.”

After entering politics, Volz served from 2007 to 2018 while in the US Congress as a member of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC), which monitors human rights and the rule of law in China.

During that time, Walz sponsored a series of resolutions advocating political freedoms in China, including a resolution in 2009 commemorating the 20th anniversary of the crackdown, as well as measures supporting human rights activists including Huang Qi (黄琦), Tan Zuoren (譚作人), and Chen Guangcheng (陳光誠). Walz also called persistently on the Chinese government to release Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波).

Walz also touched on other issues sensitive to China, such as Tibet and Hong Kong. He voiced support for Tibetan autonomy and met with the Dalai Lama, the exiled leader of Tibet. He joined a visit by US lawmakers to Tibet in November 2015 led by Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi. During that trip, the delegation met with then-Chinese Premier Li Keqiang (李克強), as well as Zhang Ping (張平), the vice chairman of the National People’s Congress, and Chen Quanguo (陳全國), secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region. In a press release following the visit, the delegation “reiterated the imperative of respect for religious freedom and expression in Tibet; autonomy and democracy in Hong Kong; and respect for human and women’s rights across China. The delegation also expressed specific concerns related to the recent arrest and detention of human rights lawyers and activists.”

On the issue of Hong Kong, he was an advocate early on in 2017 for the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, and in August of that year met with now-jailed Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong (黃之鋒), calling him “a true defender of democracy in China.” Pro-democracy activist Jeffrey Ngo Cheuk Hin (敖卓軒), a former member of Hong Kong’s Demosisto party, pointed out earlier this month that at the time of the anti-extradition protests in Hong Kong, Walz was an important advocate for the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act.

A report in Time magazine has pointed out that Walz has not expressed a clear policy position on Taiwan, but that he has taken a rather firm stance on the South China Sea issue, arguing that the US should oppose China’s actions in the region. He has also co-sponsored a bill opposing any reduction of US military personnel in the region, urging that US troop levels be maintained in order to curb the challenges of “Islamic extremism” and “Chinese expansion in the South China Sea.”

The same report also said Walz is concerned about the gap in trade between the US and China, and wants to improve their trade deficit by demanding that China abide by environmental standards, fair trade, and human rights. At the same time, he has publicly criticized Trump’s trade war footing with China, pointing out that Minnesota’s agricultural sector has been hit hard by slumping exports of commodities like soybeans and pork to China.

During an interview in 2016, Walz said that US-China relations are extremely complicated. On certain issues, the US must take a firm stance with China, he said. But relations between the two countries do not need to be adversarial and the two sides should continue to seek out areas where they can cooperate.

This story by special contributor Wing Kuang and Initium journalist Abel Yu (余美霞) was originally published in Chinese at Initium, and was translated by CMP staff.