On August 20, the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) published the findings from their latest Press Freedom Index. The results don’t bode well for the city’s increasingly difficult press environment.

Local journalists, surveyed in partnership with the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, gave Hong Kong a score of 25 for press freedom. That’s a decline of 0.7 points from the year before and a record low for the index since its inception in 2013. While the public score continued to hover around 42, more than half — 53 percent — of the randomly selected members of the public interviewed said press freedom had declined in the past year.

Journalist respondents were especially concerned about the potential impact that new national security legislation known as Article 23 — introduced in March 2024 — would have on the media. More than 90 percent of the hundreds surveyed said this would significantly impact press freedom.

The report demonstrates both the ongoing challenges facing Hong Kong journalists as well as the importance of groups like the HKJA that catalog press freedom incidents and advocate for the industry. In July 2024, the Wall Street Journal fired their reporter Selina Cheng after she was elected to chair the organization, which had been targeted by state media and local officials — a worrying indication of how the international press is complicit in the government’s ongoing crackdown on its critics. For more on this important case, see our in-depth report “Code of Silence.”

A Slow Burn

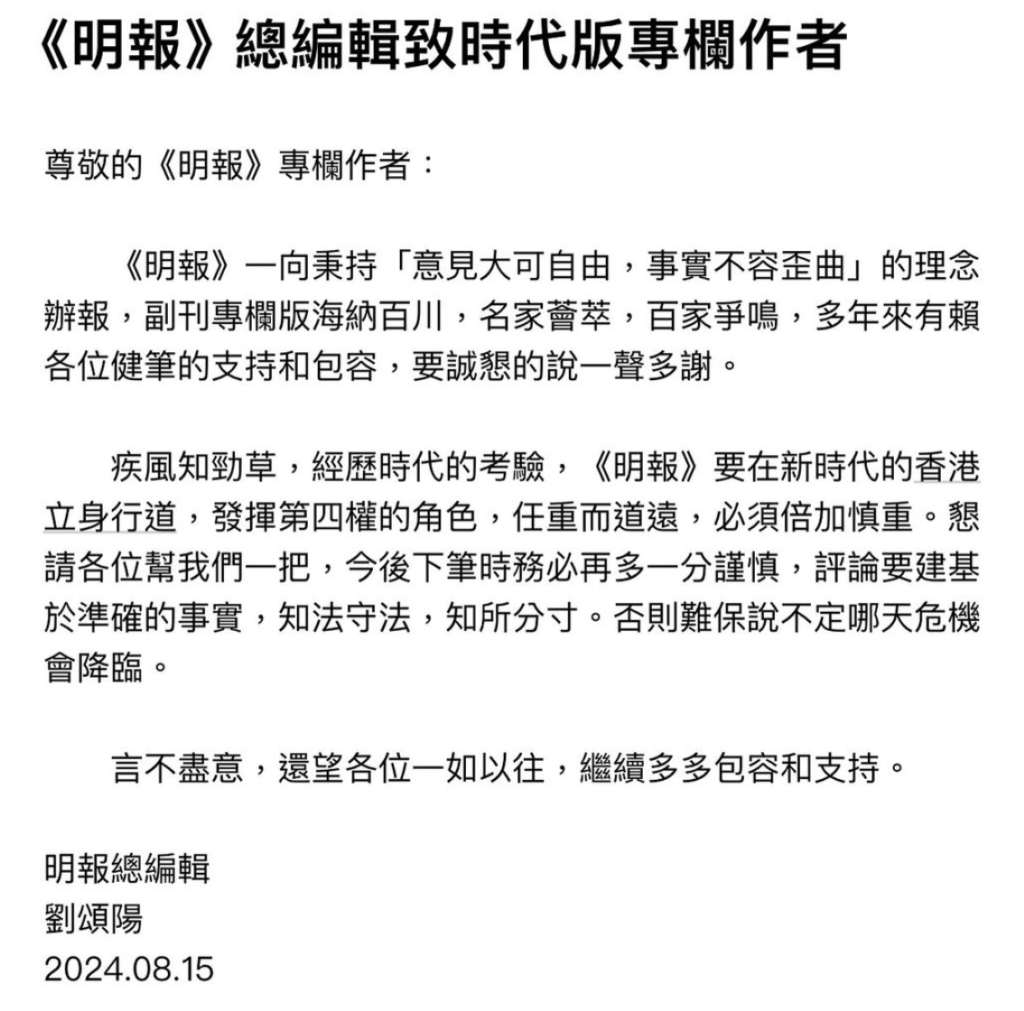

Since then, press freedom incidents have not let up. On August 15, Hong Kong’s Ming Pao (明報) — its most trusted and politically centrist Chinese-language newspaper — sent a chilling warning to its columnists. It urged them to be “prudent” and “law-abiding” when writing for the paper. If they fail to do so, “crisis may come.” Columnist and barrister Senia Ng (吳思諾) shared the full letter from Ming Pao chief editor Lau Chung-yung (劉頌陽) on social media.

“For Ming Pao to conduct itself and its mission in Hong Kong’s new era," Lau's memo read, echoing CCP language about Xi Jinping's rule constituting a bold new period in Chinese history, "as well as to exercise the role of the fourth estate, is a heavy responsibility and a long path that requires extra caution.”

This came days after security chief Chris Tang Ping-keung (鄧炳強) lambasted overseas columnists writing for the paper, who he said had “deliberately misinterpreted government policies.” A month earlier, a Ming Pao op-ed by legal scholar Johannes Chan Man Mun (陳文敏) argued that denying early release to national security offenders violates their human rights. The government condemned this as "unfounded and misleading."

All this comes in spite of a disclaimer Ming Pao added to its opinion section in early 2022. After the introduction of the 2020 national security law and the closures of pro-democracy outlets Apple Daily (蘋果日報) and Stand News (立場新聞) in 2021, the paper told its readers:

“If a commentary published by this newspaper raises criticism, it is meant to point out mistakes or flaws in the system, policy, or measure. The purpose is to facilitate the correction or elimination of such mistakes or flaws … there is absolutely no intention to incite hatred, disaffection or enmity against the government or other communities.”

Evidently, this has not been enough to shield the paper from official ire.

Closing the Gate to China

Within the same week as the Ming Pao warning, Hong Kong's press corps received another shock when Bloomberg News staffer Haze Fan (範若伊) was denied a visa to work in the city. Fan, a Chinese journalist at Bloomberg's Beijing bureau, was detained in December 2020 and was formally arrested in July 2021 on suspicion of committing crimes endangering national security. In early 2022, she was released on bail.

Fan's is merely the latest case of Hong Kong denying visas to foreign journalists or news outlets that have upset the government. In 2018 the Financial Times' Victor Mallet was effectively expelled from the territory after hosting a Foreign Correspondents' Club talk on the rise of Hong Kong nationalism. In 2020, Irish journalist Aaron McNicholas’ visa for work at the Hong Kong Free Press was rejected in the first such case at a local publication. Then, in 2020, New York Times reporter Chris Buckley’s work permit was rejected and The Economist's Sue-lin Wong experienced the same the following year. The China Media Project is also aware of at least two other journalists for major international titles who were refused Hong Kong visas but have not yet gone public with their cases.

This litany of incidents could help explain another phenomenon that the HKJA Press Freedom Index has picked up on: a widening disconnect between the perceptions of working journalists and the general public when it comes to the state of press freedom. Members of the media, who daily confront not just high-profile incidents like the closure of Apple Daily but also the slower, quieter erosion of Hong Kong’s freedoms, take a dim view of the situation. Members of the public, by contrast, actually reported a slight improvement in press freedom from the previous year.

This could come down to news fatigue and desensitization as the national security crackdown enters its fourth year. Shifting demographics could also play a part, as many expatriates and Hongkongers sympathetic to the pro-democracy movement move abroad and more mainland Chinese are incentivized to relocate there. Or it could be that officials' insistence that press freedom is thriving like never before is beginning to gain traction through sheer force of repetition, and media outlets are — all too understandably — reluctant to say they are wrong.