“Married-out women” return to their parent’s home village in a ceremonial dinner in 2024 in Guizhou province.

Xi Jinping is so proud of women and all of the “extraordinary achievements” they have made in “all walks of life,” the People’s Daily reported this week, that he sent a congratulatory letter to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Women’s Forum, which opened in the city of Qingdao on Wednesday. He praised women for their contributions to one of his flagship foreign policy concepts, the “community of shared destiny” (命运共同体).

Xi’s words exemplify how state narratives in China can utilize the language of empowerment and progress, including for women, while simultaneously reinforcing existing power structures.

When it comes to many of the concrete issues women face in China, the Party has been slow to act. In his letter, reflecting the Chinese Communist Party’s recent focus on “high-quality development,” Xi leaned again on technological and digital advancements — as though these alone could be used to spur “women’s development” (妇女事业发展). The reality, however, is that women face social, cultural, and institutional limitations — including, as statistics have shown, significant discrimination in the workplace — that are not at all technological in nature.

Last week, for the New York Times, Vivian Wang highlighted an important form of discrimination women continue to face in rural China, as those who marry outside the area of their household registration — known as “married-out women”( 外嫁女) — often face the deprivation of their rights, particularly concerning land rights and village membership. This is an issue The Economist also touched on in brief coverage last year.

In fact, the issue has quietly simmered in China for several years, as female villagers have pushed for greater attention to the systematic denial of their benefits as members of village collectives. Two and a half years ago, in February 2022, The Paper (澎湃新闻), an online news outlet under the official Shanghai United Media Group, examined the case of Fengwei Village (凤尾村) in China’s coastal Fujian province. There, residents were being systematically deprived of village benefits because they were “married-out women” or their children. The outlet described how local authorities persistently discriminated against “married-out women” and their children, withholding benefits even when a court had ruled in their favor.

The coverage by The Paper highlighted the gap between local practices and national laws, underscoring the need for more robust regulations and enforcement mechanisms. Without addressing these discrepancies, it argued, protections intended for individual rights remained ineffective — exposing a significant flaw in the implementation of legal reforms. In this instance, however, it was Lu Jing (卢景), the son of the “married-out woman,” who spoke up. Could this detail account for why the issue received more serious coverage in the Fengwei Village case?

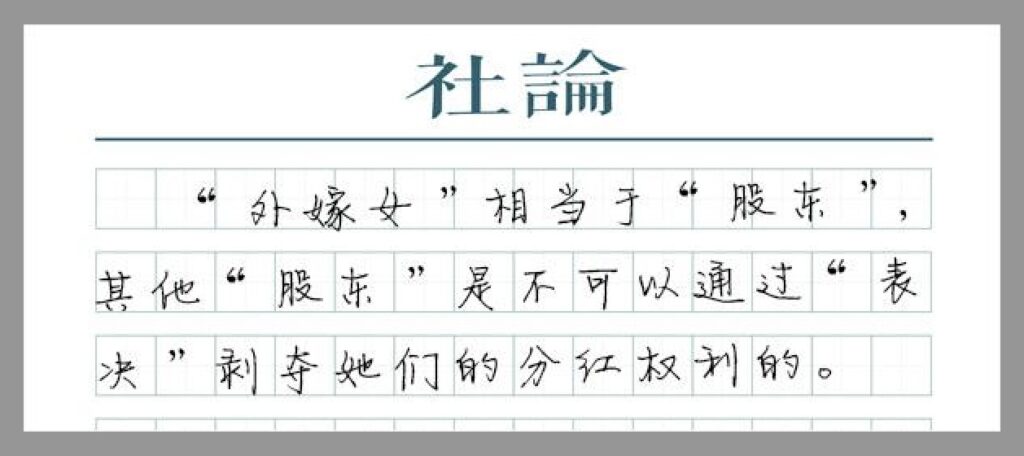

In recent years, several media outlets in China have tried to push on the concrete question of female villager disenfranchisement. A lengthy report in 2020 from The Journal of Law Application (法律适用), a periodical published by the Supreme People’s Court, laid out the legal and historical challenges in cases involving “married-out women.” An important piece of the issue, for example, has been the legal protections around village self-governance, set down in a law on Village Committees first promulgated in 1987 and amended in 1998. “Restrictions and exclusions on the property rights and interests of ‘married-out women’ often happen in the form of village rules and regulations,” The Journal of Law Application wrote, “which on the surface appear to have the legitimacy of villagers’ self-governance.”

Related cases brought by women have been on the rise since the early 2000s in China, and they seem not to have abated. A report on social media from Guangdong’s official Nanfang Daily in 2021 noted that the local government had become involved in mediation for three sisters fighting against village officials for their benefits.

For their part, state media at the central level have continued to send empowerment signals, like today’s prominent Xi Jinping letter in the People’s Daily, or to maintain the pleasant fiction that legal reforms are doing their part. One recent example comes from China Women’s News, the official newspaper of the All-China Women’s Federation, China’s official women’s rights organization. Back in May, it ran a report emphasizing the judiciary’s positive actions through related legal reforms, while conspicuously omitting critical reporting and analysis on the systemic issues standing in the way of these rights.

In the sometimes differing treatment by media at the top and those at the provincial or city levels on this issue, we can glimpse the pull between institutional inertia and media propaganda, and those who hope to make real progress — and seek real exposure — on a grassroots issue that has stubbornly persisted.

As the magazine Agricultural Wealth (农财宝典), published by Guangdong’s Nanfang Daily Newspaper Group, rightly noted nearly four years ago addressing the issue of women’s rights to village benefits, “[the] ability to safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of women and children is an important indicator of a society’s harmony, civilization and progress.”