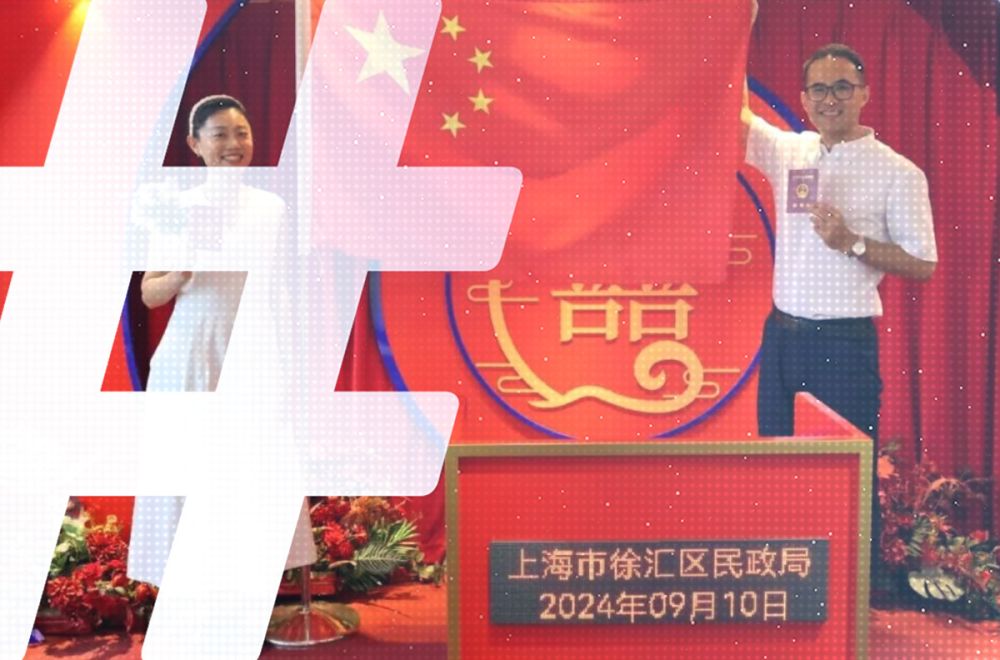

When teachers Wan Yi (万亿) and Guo Yong (郭勇) tied the knot in Shanghai on September 22, they shared their special day with over 5,100 other couples. All of them were taking part in a series of mass weddings held in 50 locations across China, organized by the country’s official women’s rights organization together with various government agencies. The Communist Party secretary for the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), Huang Xiaowei (黄晓薇), officiated the ceremony, congratulating the newlyweds for “acting as practitioners and advocates for a new marriage and child-rearing culture.”

Huang’s patriotic blessing jars with the romantic ideal of marriage as an expression of love between two individuals, but it encapsulates an increasingly prevalent attitude in PRC state media. As China struggles with a slowing economy and looming demographic crisis, the number of Chinese couples getting married has fallen to a 12-year low. And with the number of marriages closely tied to the number of births, policymakers are determined to boost the country’s shrinking population. State media is doing its part by exalting marriage and reproduction as patriot acts. At the same time, organizations like the ACWF, set up to advance women’s role in society, now harken back to their roles as mothers and caretakers instead.

Alongside the ACWF, the mass wedding was backed by China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs (民政部), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs ( 农业农村部) and the Political Work Department of the Central Military Commission (中央军委政治工作部) — a roster that signifies the issue’s importance to PRC authorities. As press coverage of the mass weddings shows, marriage is an expression of love for the motherland.

Wedding Nationalism to Natalism

Secretary Huang’s line about a “new marriage and child-rearing culture” borrows from a speech by Xi Jinping to ACWF leaders in August 2023. Xi instructed the organization to “encourage women to uphold the traditional virtues of the Chinese people” (传统美德) and “promote positive family traditions,” emphasizing the need to “actively foster a new culture of marriage and childbearing” (新型婚育文化) among the nation’s women. The goal of this new culture, as Xi put it, is to “promote the improvement and implementation of policies to support childbearing, improve demographic development, and actively cope with the aging of the population.” In simpler terms, what Xi is pushing is straightforward natalism: the pursuit of higher birth rates to promote economic growth and project greater national power.

Similar public policy concerns can be observed throughout the region. Neighboring Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan are all grappling with slowing population growth or even demographic decline and the knock-off effects on the economy. To reverse this trajectory, governments have been offering various incentives: “baby bonuses,” subsidies for assisted reproductive technology treatment, easier access to childcare and early education, and even the long-taboo topic of easing immigration. China seems to be taking a two-pronged approach, clearing some bureaucratic red tape — the Ministry of Civil Affairs introduced new proposals to streamline marriage registration in August — while also promoting a return to traditional Confucian values that hold up parenthood as both an innate virtue and a social responsibility. The more weight put on the latter, the less onerous the former will be on state expenses.

In keeping with the mass wedding’s nationwide character, news outlets from around the country covered the nuptials. In Guangdong, where close to 300 couples said their vows, the provincial Party-backed Nanfang Daily reported on a woman from Hong Kong who wed a man in Guangzhou, using the story to illustrate the advantages of the Greater Bay Area project to integrate Hong Kong more closely with nearby cities in the mainland. The newspaper also reported that 89 couples in Dongguan “issued a proposal to promote the new marriage and child-rearing culture” advocated by Xi.

The official Xinhua News Agency filed from Yinchuan, the capital of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. There, couples posed before a banner that read, “The Family and the Nation Bear Witness to Happiness Together” (家国同庆 见证幸福). In their hands, they held “Honorary Certificates for the Promotion of New-Style Rural Marriage Customs” (农村婚俗新风光荣证). Reporting from the nation’s capital, The Beijing News (新京報) offered a different perspective on the couples’ motivations, emphasizing the more practical incentives behind mass weddings. “We didn’t need to worry about the venue, make-up, photography, and other expenses,” said a groom from Jiangsu province. “It made everything so much simpler, saving us a lot of money and worry.” It isn’t hard to see how participating in a mass wedding ceremony, even one decked with propaganda slogans, just makes financial sense in this economy.

New Traditions for the New Era

Women of China (中国妇女), the official publication of the All-China Women’s Federation, devoted reams of coverage to the mass weddings over the course of the week. Besides full-spread splashes profiling couples like Wan Yi and Guo Yong in Shanghai, the paper also spoke with the “cultural consultant” for the ceremonies, Jia Wenyu (贾文峪). Jia places heavy emphasis on the aesthetics of Chinese tradition: the red lanterns, red silk, and red double-happiness symbols that, she says, “carry forward fine traditional Chinese culture” (传承中华优秀传统文化) — another of Xi’s catchphrases.

There have, however, been important “innovations” to these traditions. For instance, Jia points out, mass wedding participants did not bow to each other, to their parents, and to the heavens as tradition dictates. This was replaced with a “newlyweds’ oath” wishing glory and prosperity upon the motherland and the “extension of the family line.” These changes, says Jia, “guide each small family to be more closely connected to the greater family of the motherland, and to give thanks to the motherland with deep love and affection.” Paraphrasing Xi again, she terms this a “new style of household civilization” (家庭文明新风尚) — or, as the oath puts it, “a new style of socialist household civilization” (社会主义家庭文明新风尚). The goal, explains a civil affairs official, is to “link personal happiness with national glory.”

Back in Shanghai, Women of China tells us that Guo Yong couldn’t hold back his tears at the altar. It’s a common and relatable reaction for many grooms on their wedding day. But Guo Yong wasn’t choking up as his bride walked down the aisle or said “I do.” Instead, it was when he heard the word “motherland.” His betrothed, Wan Yi, provided this pitch-perfect line to round out the feature: “We will live up to the [New] Era. We will not let down the nation. This is our meager contribution to the great rejuvenation of the motherland.” That’s one way to characterize what others might call the happiest day of their lives.