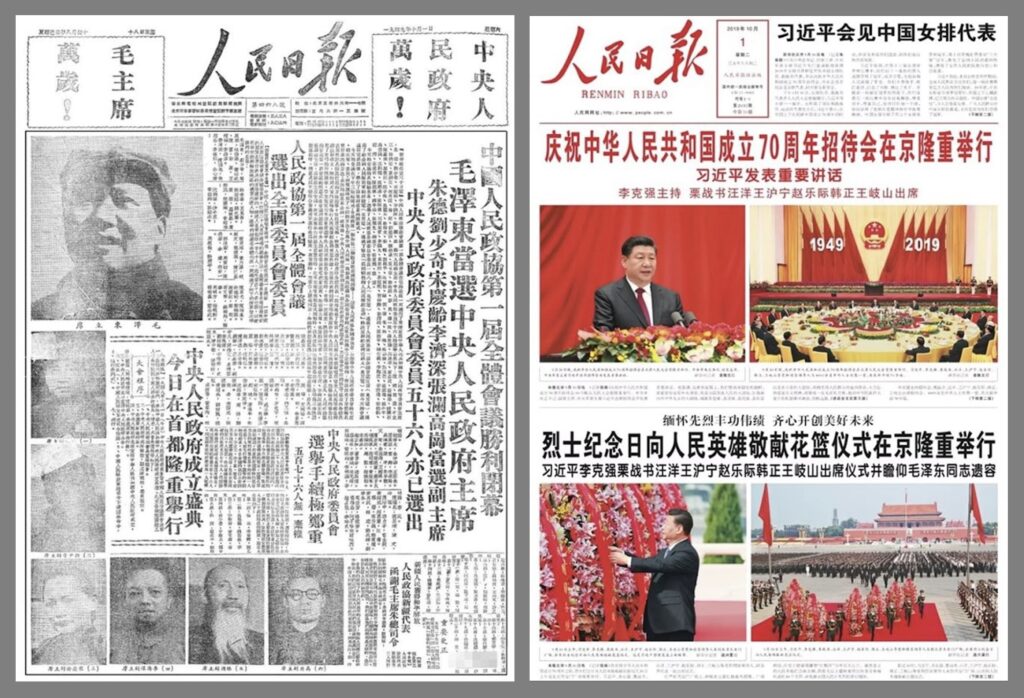

Think “state media” in China and you’re likely to conjure an image of the People’s Daily (人民日报). The daily newspaper, directly run by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Central Committee since 1948, prides itself on being the “mouthpiece” (喉舌) of the Party leadership. And a role this important demands regimentation and structure: a staid face to communicate the thoughts of the CCP core.

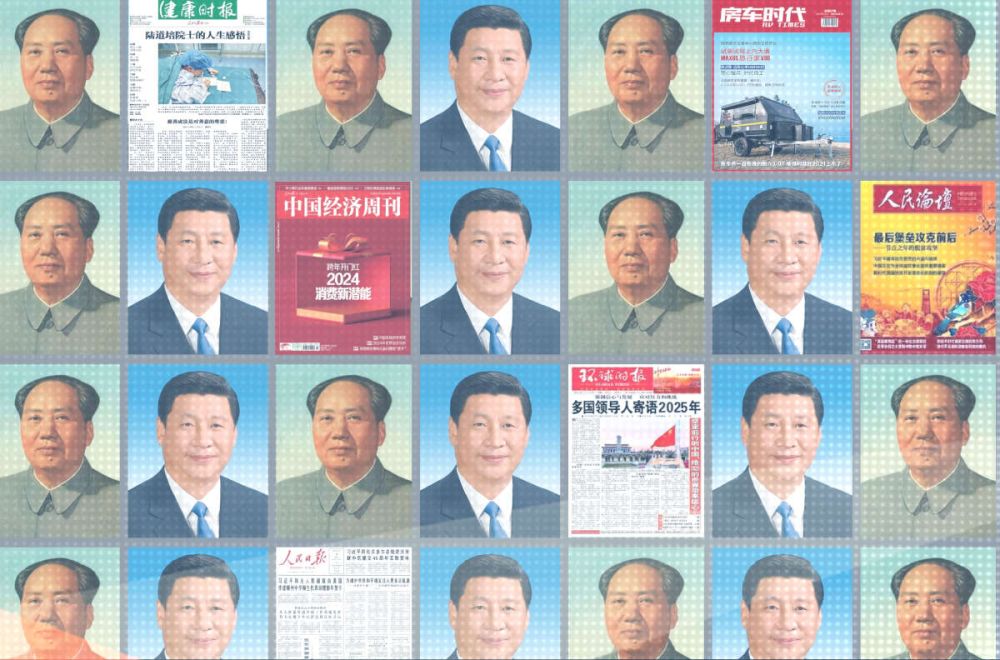

But while it is the most representative of the Party leadership, the People’s Daily newspaper, first launched in 1946, is not the only face of this Party-run media group. The paper’s parent organization, the People’s Daily Press (人民日报社), is in fact a sprawling media empire. The group oversees a portfolio of 34 periodicals as well as a wide array of newer digital products. It runs a health magazine, a history journal, a newspaper for gearheads, and even the RV Times (房车时代), a periodical for recreational vehicle enthusiasts.

The story of the group’s growth over the years is the story of the PRC media space as a whole, where commercialization and partial privatization were actively encouraged in the reform era, and where more recent developments have made it clear once again that the Party maintains ultimate control.

A Fresh Wind Through Chinese Media

In the China of Chairman Mao Zedong, the People’s Daily was one of only a handful of officially sanctioned newspapers run by the CCP — known, fittingly, as “Party-papers” (党报) — to cover the entirety of the newly founded People’s Republic of China. It adhered strictly to Mao’s notion of “politicians running the newspapers” (政治家办报), according to which any printed articles, particularly lead editorials (社论), had to be aligned with the interests of the Party. During the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (文化大革命) of 1966-1976, those interests were Mao’s personal political interests, and the chairman’s writings dominated the “two newspapers and one journal” (两报一刊) system, in which the three most influential PRC publications, including the People’s Daily, the People’s Liberation Army Daily and Red Flag journal, reigned supreme.

In the early years of China’s reform and opening up under Deng Xiaoping (邓小平), the number of nationwide publications in China remained small for a country of its size. In 1979 there were just 69 “Party-papers” in print. This contrasts sharply with the latest figures from the National Press and Publication Administration (国家新闻出版署), or NPPA, an agency under the Party’s Central Propaganda Department that supervises print publications in China. The NPPA recorded 2,405 newspapers published in the country in 2023.

This number began its climb from two to four digits in the 1980s, as economic reforms brought a rethink of the role in the media. The term “news reform” (新闻改革) signaled a new openness, including an assessment from the leadership under Deng Xiaoping that the “falsehood, bluster and emptiness” (假大空) of the media from the 1950s onward had to a large extent contributed to the chaos of the period, from the Great Famine through the Cultural Revolution.

Tragically, the push toward greater freedom of speech in the 1980s, seen in the launch of more reform-oriented newspapers like Shanghai’s World Economic Herald (世界经济导报), was brought to a brutal end by the Tiananmen Massacre of June 4, 1989.

But by the mid-1990s, as economic reforms were reinvigorated and accelerated, the spirit of change again swept over the media in China. This era also saw significant liberalization in the industry, with the number of periodicals rising rapidly as a result. Publishing was never a free marketplace of ideas — government licenses remained necessary for any operation — but new voices did begin to emerge. More market-oriented “metro papers” (都市类报纸) served China’s rapidly urbanizing population, oriented around the consumer — of goods and information. The equation meant more readers, more sales, and more ad revenue, a new way for outlets to exist independent of state financial support, even as political ties to the system remained paramount. From time to time, these papers challenged the authorities by reporting more openly on corruption and other political and social issues.

Even the People’s Daily joined the trend, launching its own metro newspaper, the Beijing Times (京华时报), in May 2001. In what has been called the “golden age for metro newspapers,” higher salaries and more comfortable working conditions made the Beijing Times and other commercial competitors attractive to a new generation of young journalists. According to a 2017 account, the “direct approach” and “sharp commentary” found at the Beijing Times in the 2000s made it “like a fresh wind sweeping through Beijing’s then-dull media market.”

Going Public with the People’s Internet

The rise of the internet in China after 1994 was another jolt for the media industry, even though it was heavily regulated from the start to ensure that news gathering remained in the hands of the Party. Inside China, Chinese-language internet portal sites like Sohu.com, launched in 1996, and Sina.com, launched in 1998, could serve as content aggregators — reposting content from Party media and registered commercial spin-offs — but could not themselves maintain teams of journalists. But they revolutionized the consumption of information, even inviting discussion in the comment (跟帖) section underneath news articles.

The People’s Daily was quick to follow suit, entering this space on January 1, 1997, with the launch of its online portal, People’s Daily Online, or renminwang (人民网). As the group’s “About Us” page explains, the emerging online space offered “unique advantages” including “communication value” (i.e., more interactivity) and “technological value.” Today, the official portal site continues to publish a digitized and downloadable version of the People’s Daily print edition, runs the Chinese Communist Party News Network (中国共产党新闻网), and moderates a “leader’s message board” (领导留言板). This last feature, which China’s government has cited as an example of democratic governance, claims to allow citizens to directly pose questions to officials or express their views, but in fact is little more than an officially curated comment service — serving to promote the idea of Party responsiveness rather than enable real accountability.

People’s Daily Online is structured more like a conventional company. Listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange as People.cn Company Limited (人民网股份有限公司) since April 2012, it has its own investor relations page and publishes its annual returns, the latest of which boasts revenues of 2.1 billion RMB (290 million dollars). Like any other company’s annual reports, People.cn’s are replete with references to the firm’s profits. But unlike those of most publicly listed companies, their reports blend profit talk with performative loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party. Investors are reminded, in the management analysis section, that the company strictly adheres to “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era.” Career openings at the company also list “loving the Party” and having “strong political integrity” as job requirements.

Building an Empire

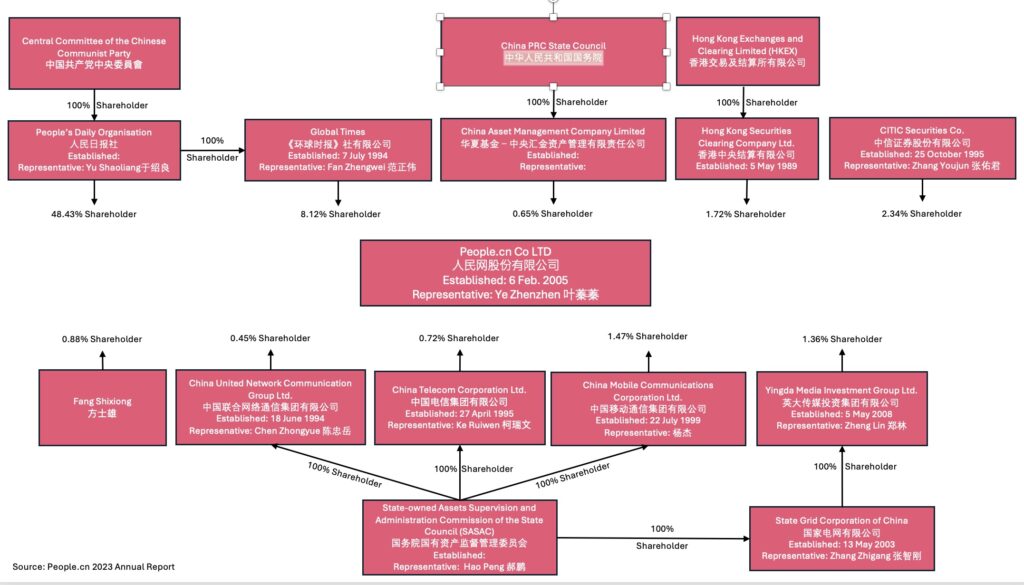

But while the print edition of the People’s Daily falls directly under the CCP’s Central Committee, People’s Daily Online has a series of private buy-ins from investors that complicate its identity. The group’s annual reports reveal their top ten shareholders, compiled into the diagram below. Amongst others, the company’s biggest investors include state-owned investment bank CITIC Securities (中心证券), state-owned telecommunications giant China Mobile (中国移动通信), and the Hong Kong Securities Company (香港中央结算), wholly owned by the Hong Kong Exchange and Clearing Limited (HKEX) that runs the territory’s stock exchange. While the print edition is run unambiguously as part of the Party-state, its online counterpart retains some reform-era features of a legitimate digital news company — although just a little digging reveals that the Party-state is still firmly in control.

Combined with the shares held by the Global Times — a nationalistic tabloid wholly owned by the People’s Daily — the People’s Daily Press has a controlling 56.55 percent stake in People.cn. Even the apparently private minority buy-ins, however, are in fact different arms of the Party-state itself. Take, for example, China Asset Management (华夏基金), which holds 0.65 percent of People’s Daily Online shares and is registered under the State Council. Other investors like China United Network Communications Group (中国联合网络通信), or “China Unicom,” China Telecom (中国电信), and China Mobile Communications are all state-owned enterprises (SOEs) overseen by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council, which is directly under the management of China’s central government.

So how profitable is the People’s Daily Online? A 2019 article in the industry publication China Newspaper Industry (中国报业) summed up media developments over the previous year in China with a series of bearish keywords. The top three: “decline” (下滑), “loss” (流失), and “avalanche” (雪崩).

While the print edition of the People’s Daily falls directly under the CCP’s Central Committee, People’s Daily Online has a series of private buy-ins from investors that complicate its identity.

But People’s Daily Online doesn’t seem to be faring so poorly. Their 2019 Annual Report logged a 40 percent profit increase from the year before, and they kept growing the next year. Despite a pandemic slump, their profits are on the rise again.

How the outlet manages to be so profitable, however, is not necessarily down to just newsstand sales, subscriptions, or advertising revenue. In the United Kingdom, the People’s Daily Online’s London bureau (People’s Daily Online UK Limited) is based near Hyde Park’s famous Speakers’ Corner, a historic site for free speech and public debate — and famous, too, for having some of the most expensive real estate in the country. The latest financial statement for the UK bureau shows a loss of 2.8 million US dollars, offset only by the 3 million US dollars provided by its head office in Beijing. We have also documented this phenomenon at China Daily USA, where the stateside operations of the state-run newspaper are run at a considerable loss thanks to millions in direct funding from China Daily HQ.

The People’s Daily Online also runs Global Times Online (环球网), the digital edition of the nationalistic tabloid Global Times (环球时报). Ownership of the newspaper is split 60-40, respectively, between the People’s Daily Online and the Global Times Press (环球时报社) — the latter of which also sits directly under the CCP Central Committee. Haiwainet (海外网), the website of the overseas edition of the People’s Daily, is split along the same lines by the People’s Daily Online and the People’s Daily Press.

China Energy and Automobile Communication Group (中国能源汽车传播集团有限公司) is responsible for the People’s Daily’s stable of specialized trade publications (专业行业报). The Group is wholly owned by the People’s Daily Press — again, directly under the Central Committee. Its properties include China City News (中国城市报), a weekly bulletin aimed at “party and government leaders” involved in “urban planning, construction, and management,” as well as China Automotive News (中国汽车报), a print weekly and digital news outlet for fans of cars and engineering.

One Voice, Many Channels

For most companies around the world, corporate social responsibility reports are used to demonstrate how the business has had a positive impact on society and the environments in which it operates. It is underpinned by the idea that for-profit institutions still have a responsibility to the broader community. The People’s Daily Press files its own “social responsibility reports” (社会责任报告), but theirs have a distinctive twist: instead of demonstrating their philanthropic deeds, they are used to demonstrate their unwavering loyalty to the Communist Party.

In their latest report, they remind readers that the outlet “strictly adheres to the principle of politicians running the newspapers” — the phrase that was first raised by Mao in the 1950s as he asserted his dominance over the media as a means of consolidating political power, and has since come back in vogue as Xi Jinping has similarly tightened controls on the media. This means that all of the group's ventures are bound ultimately to the same basic principle: Party first, profit second. This is true whether they are app-based new media outlets like Visual World (视界), at right, sending state-produced video material straight to your mobile, AI text generation tools like "Easy Write" (写易), or just the dry, Xi-filled pages of the flagship People's Daily newspaper.

Mao's old phrase, applied in state media today to stake the CCP's claim over emerging digital media, encompasses the enduring truth behind the many faces of the People’s Daily empire. While this media giant continues to transform through the process of Party-led commercialization that began in the reform era — seen in its diverse inventory of media properties — its core remains unchanged. It is still, in its own words, “the throat and tongue and eyes and ears of the CCP Central Committee.” The principle holds true whether it is reporting on the latest Party plenum or the latest make of luxury camper.