“I have not heard of such a person,” was the response given by foreign ministry spokesperson Jiang Yu at a press conference yesterday when asked about the whereabouts of celebrity Chinese blogger and CMP fellow Yang Hengjun (杨恒均). Yang, known for his outspoken advocacy of democracy and freedom through personal anecdote, has been unreachable since he reported being followed in the Guangzhou airport late Sunday.

The claim from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs that it does not know of such a person as Yang Hengjun is highly doubtful considering Yang is one of the most prominent online writers in China today and spent 20 years working at China’s foreign ministry.

Right now, facts are slim on Yang’s case. Everyone is waiting for news that might shed light on exactly what happened.

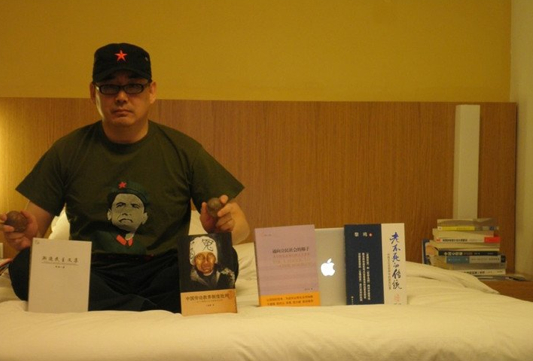

[ABOVE: A photo of “Old Yang” posted recently to his blog, in which he poses with a number of books that are banned in China.]

Until those facts emerge, here is some background of our own, a portion of the introduction to Yang Hengjun that appears in the China Media Project’s 2009 book China’s Super Bloggers, which includes Yang Hengjun as well as two others who have recently run up against trouble with the authorities, Chang Ping (长平) and Ran Yunfei (冉云飞).

Also, don’t miss our condensed CMP reading list of English translations of Yang Hengjun’s writings at the bottom. Readers of Chinese are encouraged to visit his blog site — and also browse the recent comments under the articles regarding his whereabouts.

“Yang Hengjun: I am a Democracy Huckster”

Blogs as a Link Between Those Inside and Outside the System

Yang Hengjun (杨恒均), born 1965, freelance professional.

Living long-term in Guangzhou

A former diplomat, [Yang] saw democracy at work in the Western world, and he [eventually] became a lively and acute advocate of universal values. He is also a writer of spy fiction. He use of a vivid and popular style of writing earned him admirers among a wide range of readers, including Party officials and rural workers. A group of migrant workers even established their own Yang Hengjun reading group.

When Yang Hengjun started writing his blog, people felt there was something mysterious about him. A man in his forties, and no one has any idea where he comes from, and here he is writing a blog about military affairs, national security and politics. Moreover, it was said he had written international spy fiction. For a time, opinions were widely divided. Some said that he’s one of our own, after all. Others speculated that he must be a spy.

There’s no question that Yang Hengjun is a strange one. “That’s right, I used to work inside the [Chinese] system. I was in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for twenty years, and I also worked in politics and law and other systems. Professional ethics demand I keep quiet about exactly what I did at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But what does writing a blog have to do with what I did in the past? I have a friends who are policeman, national security guys and foreign ministry people about the ministerial level, and they write blogs too. They too write their suggestions as citizens, and their ideas are much like mine. It’s just that no-one reads them.”

Yang Hengjun was in his early twenties when he graduated from from the international politics school of a certain well-known university [in China]. He was an angry youth (愤青) who knew little else beyond love of his country. After graduation, his chief work was accompanying provincial-level leaders as they went out on overseas visits, traveling to and fro in a Mercedes-Benz and staying in five-star hotels. After 1997, he was sent on state business to the United States and and other countries for more than ten years.

Slowly, Yang Hengjun’s ideas began to change. He started identifying with the core values of democracy and freedom. This [change] happened particularly after 1994, in the few years he lived in Hong Kong. Every Tuesday, he would cross the bridge [into Hong Kong] at Lo Wu, and each time was for him a lesson. Hong Kong was a place in good order. But as soon as he crossed back over the Lo Wu Bridge and reached Shenzhen, he found himself switching his backpack to his chest to protect it from thieves. How could the difference be so great between two societies so close together? “After I wrote the essay, Crossing Lo Wu Bridge (魂断罗湖桥), others said, hey, you can really write. But it’s true, that’s how my whole way of thinking was transformed.”

Yang believes that all nationalities, and all people must have core values. Chinese are not without core values, but these, [he says], are in chaos — the schools giving us one set, our family giving us another, social giving us yet another. Nor are core values such that each leader can just manufacture his own set once he steps into the top position — the Harmonious Society, or the Three Represents. Only with core values can people have peace and moderation. Money cannot bring core values, and no one will mistake money for core values. For Yang, it is quite simple. He says resolutely: “The Western core values of democracy and freedom, good. Bringing them to China, good.”

“My core values aren’t something I read in a book. They are a product of my life. That’s why I’m steadfast.”

Yang Hengjun has written a series of international spy novels beginning with “fatal” — Fatal Weakness (致命弱点), Fatal Weapon (致命武器), Fatal Assassination (致命追杀) — to convey his own political concepts. Because he wrote his PhD dissertation, “The Internet and China’s Future”, under Professor Feng Chongyi (冯崇义) at the University of Technology, Sydney, Yang Hengjun started a blog as an experiment. He never thought that once he started it he would be unable to turn back. “When I wrote novels, no one in China read them. Who reads novels anymore? But blogs are different.”

After first returning to China, Yang was alarmed by how sheltered some of his countrymen were. He remembers seeing a post with the title: “Do American city inspectors [NOTE: deputized police deployed in China to deal with migrants. I don’t believe it. City inspectors everywhere beat people.” “There are no city inspectors at all in America!” Speaking as well with Chinese overseas, Yang Hengjun found that Chinese on both sides were entirely fenced off by invisible walls. Inside China, ordinary Chinese knew precious little about the real situation outside the country, and Chinese outside China basically didn’t read blogs inside China.

“I wanted to be a bridge, talking about my experiences outside China. Talking about the changes I went through.”

As soon as Yang Hengjun started writing, the floodgates were opened. Yang had read very little aside from foreign spy novels, so his writing began by talking about life experiences. He wrote, for example, about how on his first night overseas [on assignment] he watched adult television [in a hotel] with a provincial police official, and the police official remarked with surprise that this, after all, was pornographic programming. He had incinerated mounds of pornography [back in China], but had never watched it . . . In the end he had Yang take some back with him to China. He advised [on his blog] that mainland Chinese touring in Taiwan try a very different sort of recreation — standing on one of its major thoroughfares holding up a protest sign, so they can have a taste of democracy . . . He wrote that when he saw for the first time a protester who had huddle outside the White House for some ten years, he thought he must be an American spy, put there expressly to make a display of freedom of expression . . . He has a post on his talks with a Pentagon official about China issues . . . One of his funniest posts is “Is Grandpa Hu a Bad Guy?”, which originated with his young son after they had only recently returned to China [from a long stint overseas]. Every day they watched [China Central Television’s] Nightly News. One day his son pointed to Hu Jintao and said: “Is this person a bad guy?” He thought he must be because outside China only a bad guy would make it into the top headlines every single day. Yang Hengjun laughed and told his son, no, it’s because that guy runs the television station.

YANG HENGJUN READING LIST:

“Thoughts on CCTV’s Nightly News“, March 18, 2011

“Why we all feel so vulnerable“, December 17, 2010

“How Chinese view foreign elections“, November 9, 2010

“That old pair of shoes is not democracy“, September 22, 2010

“Where is China’s center?“, August 13, 2010

“Leaders should learn from attacks on my writings“, August 8, 2010

“Why China’s ‘left’ finds favor in the West“, August 4, 2010

“Democracy is not a decorative vase“, May 17, 2010

“China Megatrends, and why I can’t hold my tongue“, May 1, 2010

“Chatting with foreign reporters on the Qinghai earthquake“, April 29, 2010