Last week China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued an official statement on the storming of Gadhafi’s compound in Tripoli by Libyan opposition forces, saying in the midst of the apparent end of Gadhafi’s rule that China “respected the choice of the Libyan people.” The ministry’s remarks generated buzz on blogs and social media in China, where some were keen to draw parallels with China’s own political situation. Blogger and CMP fellow Yang Hengjun (杨恒均) asked pointedly: “When are we going to respect the choice of the Chinese people?”

Dragging out Libya’s lessons for China is of course a sensitive issue, and few traditional media have tackled the question even indirectly. One editorial in particular is worthy of note, however.

On August 26, Shanghai’s Oriental Morning Post, which has distinguished itself as one of China’s hardest-hitting publications since playing a key role in breaking the 2008 poisoned milk scandal, ran a lead editorial called, “Give the People a Choice, Give Everyone a Route of Escape.”

While the editorial was about Gadhafi and Libya, its implications for China were not far beneath the surface. It argued that those in power must learn from the lessons of history and ensure that the “people’s right to choose” is respected. Leaders and vested interests who fail to do so pave the way not only for their own undoing, but they close all paths of escape for the whole society, leaving violence as the only means of change.

The editorial concludes with a clear reference to China’s dynastic past and the rise and fall of political rulers: “The men of the Qin had no time for sorrow [so swiftly did they fall], but was pitied instead by those who followed, even as they failed to learn its lessons, sowing the pity of future generations for themselves.”

The Oriental Morning Post editorial was quickly removed from the newspaper’s website, which now yields the following 404 error.

The editorial was then actively shared on social media using online services that instantly convert text into images that can more easily elude censors using keyword filtering methods.

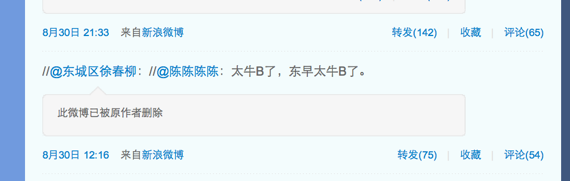

Censors eventually caught up. The following is a screenshot of a re-post of an image-based version of the Oriental Morning Post editorial on Sina Microblog, which now carries the message: “This post has been deleted by its original author.” The Sina notice once again begs the question of whether this was really a voluntary deletion on the part of the user, or whether A) the user was asked by managers to remove the post or B) managers removed the post themselves and attributed the action to the user. This is something we’re looking into for this and a number of other cases.

The message from the user who re-sent the original microblog post reads: “This is just awesome! The Oriental Morning Post is awesome!”

Below is a partial translation (mostly complete) of the August 26 Oriental Morning Post editorial as re-posted on Sina Microblog. The user added a note to the top of the image-text file saying that the article had already been deleted from the internet.

As usual, recognizing that our time constraints do not permit perfection, we humbly invite comments and clarifications on translations or other issues.

“Give the People a Choice, Give Everyone a Route of Escape”

Oriental Morning Post

August 26, 2011

(already deleted from the website, but visible in photograph form)

Everything that has happened in Libya up to now only proves yet again the inevitable proposition that if people are not given the right to choose, this shuts off the path to peaceful negotiation and closes off all routes of escape available to the whole of society, those in power included.

On the situation in Libya, the position of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was this: “We have noted the changes in the situation in Libya in recent days, and China respects the choice of the Libyan people.” The significance of this statement lies first of all in the fact that it admits that the subject of change in Libya over the last six months and more has been the “people.” Second, it is significant because it admits that the fulsome struggles of the Libyan people in action over the past half year have been an exercise of their “right to choose,” and that [the exercise of this right] is normal and should be respected.

This wave of political change has spread, one after another, through many nations in the Middle East, so why was Libya singled out for attention [by the foreign ministry]? Clearly, this is because changes in other countries were swift and clean while changes in Libya came about only as the culmination of more than half a year of bloody civil war.

The Libyan people have paid a heavy price to realize their right to choose. The whole of Libyan society has suffered, including Gadhafi and his supporters. Many of the costs will become evident only in the future. It is difficult to say how the social scars of civil war and domestic enmities will impact the unfolding political situation in Libya. Blood and fire may voice the determination, courage and honor of the Libyan people in seeking their freedom, but they cannot heal the country’s wounds or dispel deep-seated concerns.

In this sense, the “weakness” of rulers in Tunisia, Egypt and other countries made it possible under particular circumstances for these countries and their people to avoid, much to their benefit, the path of violence . . .

Look at Gadhafi and how he was given the opportunity to compromise, but how he failed to cherish this opportunity. Violence was his only religion, and he wished to use the blood of the opposition to plunge the whole nation into war. By the time his mind turned to compromise, the opportunity had passed.

Of course, Gadhafi’s refusal to compromise has always been done in the name of “the people of Libya.” It’s certainly no secret that his use of the word “people” has from the very first day tallied a lousy record of misrepresentation and abuse. Today we understand that Gadhafi does not in fact represent “the people.” In truth, he and the forces he represents stand in opposition to the people of Libya.

But this is not something that was apparent only after the writing was on the wall. It could be seen on the day they threatened and massacred their own people, and even earlier, on the day they robbed the people of their right to choose. It was then that they cleaved themselves from “the people.”

It was his psychology of “whoever stands at the end represents the people,” or “victory justifies the victorious,” that made Gadhafi refuse to set violence aside. His logic, in which whoever is smiling in the end represents the will of the people, is at base a philosophy of violence, of the supremacy of arms. The natural outcome of this logic is that when those in power have lost all popular support, and when the people have no prospect of using legal means and procedures to exercise their right to choose, violent overthrow is their only alternative. [Under such a political environment] words and promises of negotiation, deliberation and “reform” are often no more than policies of deception. From the day the people’s right to choose was no longer respected, or was even trampled, Gadhafi left no exit for the people, and he left no way out for himself either . . .

Gadhafi came to power through violence, and he made his exit in the midst of violence. The difference is that in leaving power, he left behind even more blood, leaving Libya with wounds from which it will be all the more difficult to recover. When there is an unwillingness to face the existence of the people, when the people are not permitted to voice their own demands, when the people are not allowed to exercise their right to choose, the only form of change that remains is ultimately the fiercest, most extreme and bloodiest . . .

Broadly speaking, every change in the nature of society, every rebalancing of power and interests, is a transformation (变革). But owing to different attitudes toward the choices of the people [by those in power], the outcomes will be markedly different. There might be a gradual process of improvement, or there might the terrible prospect of “a successful revolution, in which millions fall to the earth.” On the other hand, of course, there is the possibility that revolution will not succeed, and millions will fall to the earth still. There have been many such terrible precedents. [NOTE: The portion here in Chinese referring to unsuccessful revolutions is a reference to the words of Sun Yat-sen, who said that if the Chinese revolution was not successful, the people must push on.]

The core measure of a civilized society is not how those in power came to be in power, but how they step down. When [those in power] are seduced by the desire to protect their personal interests, or those of their families or cliques, when they are tempted to grasp power firmly for all time, and will stoop to any false or fabricated notion of the popular will to extend their own legitimacy, then they ultimately leave the people no choice but to choose the extreme path of indiscriminate destruction. When such a situation emerges, the people may not understand or be adept at how to employ peaceful means to voice their demands, but given the fact of an authoritarian society, responsibility must be placed first on the shoulders of those rulers who lack political wisdom and a sense of historical undertaking.

Each and every day there might be powers big or small that exit the center of power [in this or that country]. The biggest difference between them is the extent to which they affirm the right of the people to choose and submit themselves to it. “When I left the Kremlin, hundreds of reporters thought I would weep. I did not weep, because I had already attained the chief goal of my life. For a true politician, this goal is not to hang on to one’s power and position, but to promote progress and democracy in one’s country.” These words were spoken by Gorbachev. Twenty years ago, he relinquished power. His merits and shortcomings will be determined by future generations. But we must at least admit this, that while those nations in transition, including Russia, have struggled through dramatic changes, little or no blood was shed. Meanwhile, Libya, which for such a long time was “stable” (but in fact stagnating) now faces terrible social divisions.

Gadhafi’s error was a pernicious and ancient illness repeated by men through the ages: “The men of the Qin had no time for sorrow [so swiftly did they fall], but were pitied instead by those who followed, even as they failed to learn its lessons, sowing the pity of future generations for themselves.” The people must be granted the right to choose gradually but resolutely, otherwise the frightening prospect of having no escape [from violence] will be the recurring nightmare facing any society in transition.

——————–

给人民选择权, 给所有人退路

August 26, 2011

迄今为止在利比亚发生的一切,只是再次证明了一个千古皆然的政治命题:不给人民选择的权利,就堵死了和平协商的变革路径,也会堵死包括掌权者在内的整个社会的退路。

对利比亚局势,中国外交部的表态是:“我们注意到了近日利比亚形势发生的变化,中方尊重利比亚人民的选择。”这个表态的意义,首先是承认利比亚半年多来变局的主体是“人民”,其次是承认这半年来利比亚人民充满折腾意味的行动,只是为了行使“选择的权利”,正当,应予尊重。

此轮政治变革先后波及多个中东国家,何以利比亚受到格外关注?显然,是因为前述几国变革急骤而利落,惟有利比亚的变革,是通过内战这种大规模流血的方式,前后迁延半年之久,才终于得以实现。

利比亚人民为实现选择权利付出的代价是惨重的。受到重创的是整个利比亚社会,包括卡扎菲家族及其支持者。代价还将在未来体现,内战造成的社会裂痕、家国仇恨会怎样影响利比亚政局走势,尚属难言。血与火固然能表明利比亚人民争取自由的决心、勇气,为他们带来荣誉,却不能抹平既成的伤口,消解未来的隐忧。

从这一点上说,突尼斯、埃及等国统治者的“脆弱”在特定情况下,却避免了兵火之灾,不啻是这些国家国民与社会的福分。不必为一个人、一个家族或者一个政治团体的私利,让全社会付出巨大代价,这是利比亚人民求之未得的。

反观卡扎菲,曾经有妥协的机会摆在他面前,但是他没有珍惜。他只迷信暴力,他要用反对派的血,来让所有的子民战栗。等到他想起了妥协的好,时机早已远去。

当然,卡扎菲的不妥协,一直是以“利比亚人民”的名义而行的。这不是什么秘密——“人民”一词从出现的第一天起,就充满了被挟持、滥用的不良记录。多少罪恶以“人民”之名行之。今天,我们知道卡扎菲并不是真正代表“人民”的。事实上,他和他代表的力量站在了利比亚人民的对立面。但这一点不是在他大势已去时才能判断,而是在他威胁屠杀自己的国民那一天,甚至更早——从他剥夺了人民的选择权那一天起,就与“人民”分道扬镳了。正是“谁坚持到最后,谁就代表人民”,或者说,“成王败寇”的心理,使卡扎菲执意不放弃暴力。谁笑到最后谁就代表民心所向的逻辑,实质上鼓吹的是一种暴力思维、“枪杆子至上”思维。由此逻辑能得出的惟一结论就是,即便一个政权的统治力量已经失去了民心的支持,也不能指望其让人民通过法定的程序行使选择的权利,除非用暴力推翻它。妥协、谈判、“改革”,这些词语或承诺即使有,也常常只是一种欺骗策略。从不再尊重乃至剥夺人民的选择权那一天,卡扎菲就没有为人民留下退路,也没有为自己留下退路,全不管“死后洪水滔滔”。

卡扎菲由暴力上台,也由暴力下台。不同的是,他下台时,流了更多的血,利比亚这个国家留下了更加难以痊愈的伤口。不愿正视人民的存在,不让人民表达自己的诉求,不准人民行使选择的权利,最后收获的,却是最激烈、最极端、最血腥的变革形式。此时,这当年的革命者,还能谈什么对国家民族的责任?

广而言之,每一种社会形态改变、利益与权力的重新分配,都是变革。但由于对待人民选择权态度不同,结局会有天壤之别:可能是和风细雨的渐进改良,也可以是“革命成功,千万人头落地”的恐怖图景。从另一面讲,“革命未能成功”,同样会有“千万人头落地”的可能。这种恶例更多。

文明社会的核心指标,不是掌权者如何上台,而是掌权者如何下台。面临保住个人、家族或小集团利益的诱惑,面临将权力把持千秋万代的诱惑,不惜以谎言和伪造的民意来增强自己的合法性,最终,却往往使人民不得不选择玉石俱焚的极端手段。出现这种局面,可能有民众不懂得、不善于通过和平手段表达诉求的因素,但在威权社会的现实背景下,首先必定归咎于缺乏政治智慧也缺乏历史担当的掌权者。

几乎每天都会有大大小小的掌权者离开权力中心。他们之间的最大区别,在于是否承认人民选择的权利并确实臣服于它。“当我离开克里姆林宫时,上百的记者们以为我会哭泣。我没有哭,因为我生活的主要目的已达到,对于一个真正的政治家来说,其目的不是保卫自己的权力和地位,而是推进国家的进步和民主。”说这句话的人叫戈尔巴乔夫。20年前,他放弃了权力。他的千秋功罪,尚待后人评说,但我们至少需要承认一点:包括俄罗斯在内的那些转型国家,尽管经历了巨变与折腾,但几乎没有流血;而长期“稳定”(实则停滞)的利比亚,如今却面临着可怕的社会裂痕。

卡扎菲的错误,是一种古老的痼疾,前有古人,后有来者,“秦人不暇自哀,而后人哀之,后人哀之而不鉴之,亦使后人而复哀后人也”。除非逐步但坚决地给人民选择的权利,否则,全社会退无可退的可怕图景,终会是每个转型社会挥之不去的梦魇。