By QIAN GANG

Keyword: stability preservation (维护稳定/维稳)

On July 21, 2012, torrential rains devastated China’s capital, Beijing. The ensuing floods claimed at least 77 lives, according to official numbers. The tragedy, which state media were quick to characterize as a “natural disaster,” in fact exposed the extreme deficiencies of Beijing’s municipal administration. In a panic, leaders leapt onto the defensive, and the phrase “stability preservation” came leaping into the headlines:

[ABOVE: The front page of the July 23, 2012, edition of the official Beijing Daily. The top headline reads: “The Focus of Work Has Now Shifted To Stability Preservation in the Wake of Disaster Relief.”]

The two-character Chinese phrase weiwen is an abbreviated form of the full phrase, weihu wending, meaning to preserve or safeguard stability. The Chinese Communist Party has many such shortened phrases, compact verbalisms that pack a political punch, invoking whole histories of policy and practice. For those versed in China’s political vocabulary, these are important shibboleths.

In the phrase “stability preservation,” stability is a coded reference to social disorder — which is to say, social disorder must be avoided at all cost.

In the chaos that followed the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong talked about the need for “tranquility and unity.” In the 1980s, as social tensions became more acute, Deng Xiaoping first used the word “tranquility,” or “anding,” and later opted instead for “stability,” or “wending.”

Meeting with U.S. President George H.W. Bush on February 26, 1989, Deng Xiaoping said: “Before everything else, China’s problems require stability.” In the aftermath of the Tiananmen crackdown just over three months later, Deng again stressed this point in what quickly became a hardened phrase: “Stability is of overriding importance.”

The phrase “wending yadao yiqie” could also be translated as “stability above everything else.” This term’s coming of age, you might say, was heralded when it became a headline in the People’s Daily on the one-year anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown in 1990.

[ABOVE: In June 1990 the Party’s official People’s Daily includes the phrase “stability above everything else” in a headline.]

“Stability above everything else” is a slogan much beloved by Party leaders associated with the conservative faction, or baoshoupai, who oppose reforms in China. When Deng Xiaoping used this phrase, however, he used it in conjunction with his advocacy of reform and development.

When Jiang Zemin passed the baton on to Hu Jintao in 2002, a careful balance of these three ideas — stability, reform and development — was maintained. The full phrase, “Stability above everything else,” this hard-edged watchword, did not appear at all in either of Jiang Zemin’s political reports to the 14th and 15th national congresses in 1992 and 1997. The phrase did sneak into the political report to the 16th National Congress in 2002, the year when Hu Jintao took the presidency, but it was dropped again in the political report five years later.

Unrest in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China’s remote northwest, in the summer of 2009 brought a momentary change in this watchword’s fortunes. For some time after Urumqi, “Stability above everything else” made a strong showing in China’s media.

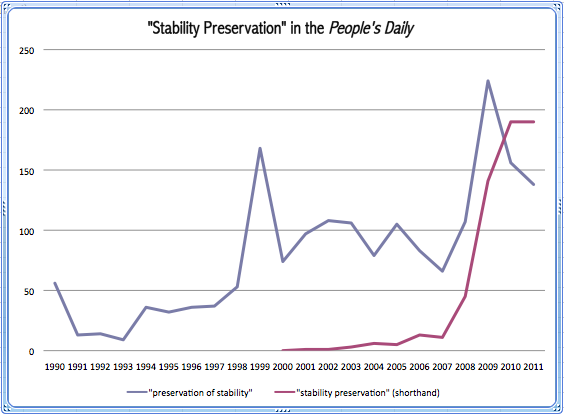

Over time, the phrase “stability preservation” has been used with greater regularity in the Chinese media. From June 1989 to July 2012, there were three peaks in the use of the phrase. The first was in 1990, the year after the Tiananmen crackdown. The second came in 1999, as the Party launched a concerted campaign against the Falun Gong religious sect. Finally, there was peak in use in 2009, which marked the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

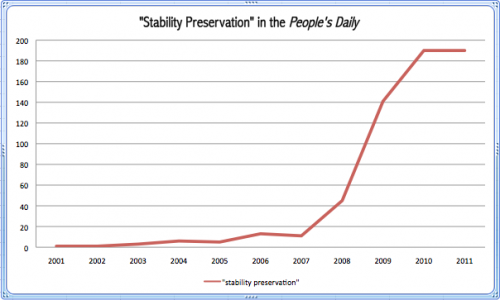

Terms like “stability preservation” and “incident handling”, or chutu, short for “handling sudden-breaking incidents” (such as mass riots), are now used as a matter of routine by armed police divisions in China. The shortened form of “stability preservation,” weiwen, was used for the first time in the official People’s Daily in 2002, in the explanation accompanying a photograph of armed police. The term reached new heights of popularity in 2008 and 2009, and has maintained a high rate of use in China’s media ever since.

In this way, a term that had been used routinely only inside China’s police system became one of the Party’s key political watchwords. There are now many related buzzwords, phrases like “stability preservation work,” “stability preservation outlays,” the “stability preservation office,” and “stability preservation teleconference.”

In China’s Hunan province, one county has even come up with a “stability preservation security deposit.” Party leaders throughout the county now have 150 yuan withheld from their monthly wages, and if there are no so-called “mass incidents,” or cases of unrest, on their watch, this money is paid to the officials at year’s end.

As the phrase “stability preservation” has risen in prominence, so has the influence of officials associated with the Central Politics and Law Commission, the Party organization that takes charge of political and legal affairs in the country.

The People’s Daily has even applied the term “stability preservation” to international affairs, as in this article dealing with the recent Libyan civil war, which bears the headline: “Libya Faces ‘Stability Preservation’ Challenge.”

[ABOVE: A headline in the official People’s Daily uses the Party notion of “stability preservation” to frame unrest in Libya.]

Some within China have referred to the 10 years of President Hu Jintao’s leadership as the “stability preservation decade.” During these years, political reform has stalled as an agenda item, and powerful interest groups have hijacked politics and the economy.

As China’s national strength has advanced, China’s population at large has paid a heavy toll. Social inequality in China has worsened substantially. Facing a growing tide of rights-defense movements by disenfranchised Chinese, the response by Party authorities has been to apply pressure on top of pressure. This has sometimes been called “maintaining a high-pressure environment.” Its net result has been a constant outbreak of violent incidents. When thousands of residents in the Sichuanese city of Shifang took to the streets in July 2012 to protest the building of a copper alloy plant close to residential areas, the local government responded by mobilizing armed police, who sought to clear the streets in tightly advancing formations, even firing stun grenades at protesters.

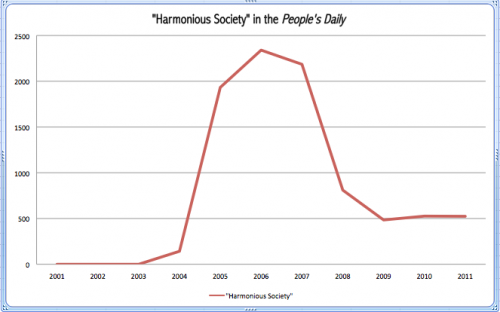

When Hu Jintao came to power in 2002, China was already experiencing a worsening social crisis. In 2004, President Hu offered a rhetorical response to growing internal instability, trumpeting what he called a “harmonious society.” For some time, this new watchword burgeoned, becoming visible everywhere in the Party’s propaganda. But by 2007 it was already on the decline, as “stability preservation” made its rapid ascent. Here you can see both terms as they appeared in the People’s Daily from 2003.

Together, these contrasting pictures of the “harmonious society” and “stability preservation” form a portrait of the real predicament facing President Hu Jintao. A “harmonious society” may be a pleasing idea, but it’s the iron will behind “stability preservation” that packs the real punch. This fact was brought home for many Chinese internet users by the following photograph in which men in fatigues march bearing a red sign that reads: “Building a Harmonious Society.” The appended caption, as the photo was shared online, became: “Who Would Dare Be Unharmonious?”

[ABOVE: A photograph circulated widely on Sina Weibo, a leading social media platform in China, depicting riot police marching with a red sign that reads, “Building a Harmonious Society.”]

In the midst of the 2012 Bo Xilai Incident, as the actions of police in the city of Chongqing — hitherto treated as principled, resolute and efficient heroes — were scrutinized and tainted with allegations of corruption, China’s entire police bureaucracy was subjected to criticism. This leaves open the question of how influential the forces of “stability preservation” will remain within the mix of China’s Party politics. We will have to wait and see how the 18th National Congress deals with the issue of “stability preservation.” In terms of Party watchwords, this leaves us with two important questions:

1. Will the phrase “stability is of overriding importance” appear in the political report?

2. Will the phrase “stability preservation” appear in the political report?

If these terms do appear, this will signal that the Party intends to perpetuate the political line of “stability preservation,” and maintain an atmosphere of high pressure on all perceived forms of unrest, regardless of how legitimate the claims of those carrying out rights defense may be. If these terms do not appear in the political report, the question will be how the report deals with the agenda of social stability, and whether there are watchwords of change to read between the lines.