There is now little doubt that the defining ideological debate in China this year will be that between constitutionalism and socialism.

For the beginnings of this story we have to wind back to early December last year, when Xi Jinping marked the 30th anniversary of China’s 1982 Constitution by saying: “We must firmly establish, throughout society, the authority of the Constitution and the law and allow the overwhelming masses to fully believe in the law.” Xi also said that “[no] organization or individual has the privilege to overstep the Constitution and the law, and any violation of the Constitution and the law must be investigated.”

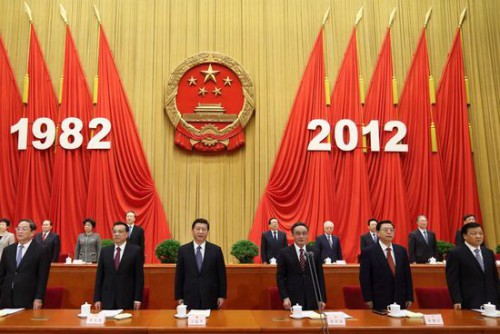

[ABOVE: Xi Jinping speaks during 30th anniversary celebrations for China’s Constitution on December 5, 2012.]

Right on the heels of Xi Jinping’s speech, it became clear that political reform advocates in China were drawing strategic inspiration from Xi’s remarks, that they saw “firmly establishing the Constitution” as the ideal moderate strategy to push change on the basis of a document that already — or so they argued — constituted and represented a political consensus.

The Southern Weekly incident in January 2013 and the year’s inaugural edition of the journal Yanhuang Chunqiu (“The Constitution is a Consensus for Political Reform“) were a throwing down of the gauntlet. (READ: “Reformers Aim to Get China to Live Up to Own Constitution,” NYT, February 3, 2013.)

By late spring and early summer, the counterattacks against constitutionalism as a new way of framing the political reform debate had become relentless. Notable was a series of editorials in the Red Flag journal, which we wrote about here.

Most recently, there were three editorials in the overseas edition of the Party’s official People’s Daily, all issuing colorful attacks on constitutionalism (one likening it to “trying to catch fish in the trees”). The first of these editorials baldly declared: “Constitutionalism only belongs to capitalism, and it is not compatible with socialism” (宪政只属于资本主义,和社会主义无法兼容.).

It must be emphasized that the overseas edition of the People’s Daily IS NOT, exactly, the People’s Daily, by which I mean it cannot be construed as representing an official view to the extent that (albeit very problematically) the China edition of the People’s Daily can. That sounds complicated, I know. But just remember that even the hometown People’s Daily can become a battleground for internal Party struggles, and so is not a simple reflection of consensus. [READ: “What’s Up With the People’s Daily?“]

In this case, the overseas edition of the People’s Daily is being exploited by opponents of the constitutionalism drive, a case (if you will) of hitting line balls (打擦边球) politically. They are trading on the confusion over the nature and purpose of the overseas edition of the People’s Daily to try to suggest their views on constitutionalism are dominant and overriding.

There are still plenty of other voices out there on this issue that are worth reading. I’ll share just a couple.

Earlier this week, Yuan Ling (袁凌), the Caijing magazine feature writer and CMP fellow best known for his recent groundbreaking investigation of the Masanjia labor camp, wrote a long piece based on an in-depth interviews with the prominent legal scholar Jiang Ping (江平). In the piece, Jiang suggest the framing of this issue as a face-off between constitutionalism and socialism is entirely misleading, that the fundamental goals of both are compatible.

The following is just a taste:

“Jiang Ping: Socialism is a Good Thing, Not Incompatible with Constitutionalism“

August 12, 2013

Caijing, Yuan Ling (袁凌)

“I often say to He Weifang that socialism is a good thing, not something incompatible like fire and water with constitutionalism. Stalin and the Cultural Revolution, these were about dictatorship, not about socialism.” In his flat in Baolong Hot Springs Apartments, this is what the 83 year-old Jiang Ping has to say about the controversy over “socialism and constitutionalism.” This is the question he has thought about the most recently.

In Jiang Ping’s eyes, socialism is about fairness and justice, and this is inseparable from, and can work in concert with, the freedom and rule of law that constitutionalism represent, thereby arriving at the greatest point of commonality.

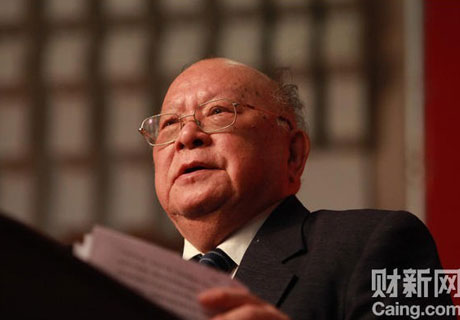

[ABOVE: Legal scholar Jiang Ping. Image by Caixin Online.]

A half century ago, a distortion happened between these two [socialism and constitutionalism] that resulted in a generation of disaster, and resulted also in the young Jiang Ping being branded a rightist. As Jiang Ping tells it, he was just one egg fortunate enough to have survived after the whole basket was overturned, though his shell had already been cracked.

But Jiang Ping suggests that a more apt metaphor might be a railroad tie under the train, that while it has been crushed by the force of the train going off the rails still remains unbroken, and still can bear up the pressures of the times and form a piece of the tracks leading on to rule of law; and then there is a new germination of ideas in its shade. This, perhaps, is one of the messages conveyed by the title of Jiang Ping’s oral memoir, Sinking and Rising (沉浮与枯荣).

The mind of this “railroad tie that is capable of thinking” is still turning, crying out, searching.

The next piece is written by Wang Jianxun (王建勋), an expert in constitutional law who also earned a PhD in political science at Indiana University-Bloomington. The piece, “How I See Constitutionalism,” appears in the latest edition of Yuanhuang Chunqiu.

Wang’s piece is framed as a straightforward explanation (Political Science 101) of what constitutionalism is all about — much needed considering the flood of claptrap the issue is getting.

Here is a taste:

“How I See Constitutionalism“

August 12, 2013

Wang Jianxun (王建勋)

Yanhuang Chunqiu

Recently, quite a number of publications have run pieces criticizing constitutionalism. This is something we’ve not seen very frequently over the past 100 years of our history. Since constitutional reforms were undertaken at the end of the Qing Dynasty, aside from those periods of totalitarian rule, the journey to constitutionalism has remained a fundamental bottom-line consensus for the people of our country.

Since these voices against constitutionalism emerged, not only have they been met with constant counter-criticism, but they have ignited a debate about constitutionalism within intellectual circles. We have seen in particular an ongoing debate between the “socialist constitutionalism camp” (社会主义宪政派 or 社宪派) and the “general constitutionalism camp” (泛宪派 or 普宪派). This debate has on the one hand exposed a deficiency of constitutional knowledge among the theoretical set (理论界), and on the other hand shown that people imagine very different things when they think about realizing constitutionalism. Against this backdrop, it’s of utmost urgency in China right now to clear up what constitutionalism actually means.

So what does “constitutionalism” mean? In a word, constitutionalism is a concept and a set of institutional insurances for checking the power of the government and protecting the basic rights and freedoms of individuals. Constitutionalism also entails a prescribed state of governance, in which checks on power and the primacy of law are effectively implemented. In this state, the power of the government is effectively limited, and the basic rights and freedoms of the individual are adequately protected. The core of constitutionalism is the limiting of power, and to this day, the most effective means discovered by humankind for the limiting of power is its separation, including horizontal decentralization (横向的分权) and vertical decentralization (纵向的分权). The first is what is called “separation of powers” (三权分立), and it means that legislative, executive and judicial powers are separate with mutual checks and balances. The latter is called “federalism” (联邦主义), and it means that national government and various local governments are separate with mutual checks and balances.