On March 29, CMP director Qian Gang attended the Annual Kam Yiu-yu Press Freedom Awards in Hong Kong and gave the following address on the struggle for freedom of speech in China since the 1989 June 4th Incident. The Kam Yiu-yu Press Freedom Awards are named in honour of former Wen Wei Po editor-in-chief Kam Yiu-yu (金尧如).

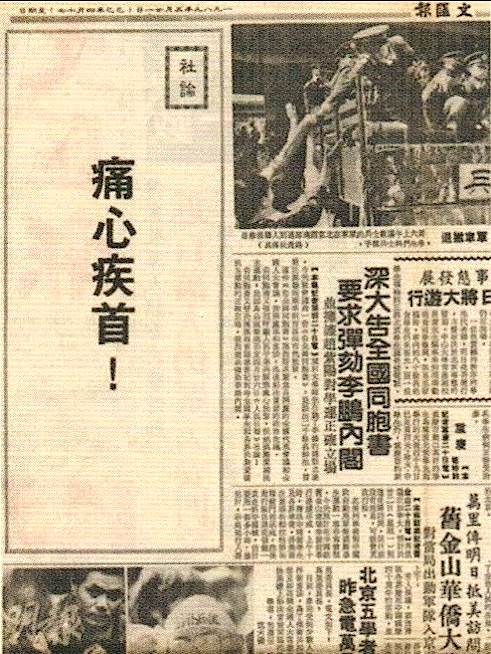

After martial law was declared in China in May 1989, Kam and other top editors at the CCP-aligned Hong Kong paper made the decision to leave a blank space, or tian chuang (天窗), in place of their lead editorial as an expression of protest.

The text in the blank space read simply: “Bitter and hateful lamentations!”

My friends:

It’s already been twenty-five years since the June 4th Incident of 1989. At that time I was a reporter at the Liberation Army Daily in Beijing, and I became embroiled in events that spring.

In April, the editor-in-chief of Shanghai’s World Economic Herald, Qin Benli, faced dismissal from his post because the paper had dared to run an article mourning the death of Hu Yaobang. As a personal decision, I sent a telegram to Qin voicing my support:The full honor of history is yours, Qin Benli, pioneer of freedom of speech in China.

That May the students began their hunger strikes, and I went with a friend to Tiananmen Square to visit with them. Because of these two things, I was stripped of my post and removed from the army in the purges that came after.

Working in Beijing at the time, I already knew the editor-in-chief of Hong Kong’s Wen Wei Po, Lee Tze Chung, and Ching Cheong and Lau Yui-siu and I were already friends. The image of Yui-siu driving this old truck and speeding all over Beijing to interview students is burned deep into my memory. I had urged my own team of PLA Daily reporters to study Yiu-sui’s example as a model of professional journalism.

It’s been 25 years. Since the June 4th Incident, China’s journalists have spent another quarter century on the arduous road to freedom of speech.

My hosts have invited me to talk about the road we’ve traveled over the past 25 years. That’s not an easy ask, because there have been so many frustrations — and yet, so many changes too. Indulge me for just ten minutes as I make a simple sketch of this period in history.

We can see today that there have been five actors, or factors, that have been closely connected to the struggle for freedom of speech. These are: political power, the news media, the market economy, information technology and civil society. More concisely, let’s call them: power, media, market, technology and citizens. On the question of freedom of speech, these five things have interacted, counteracted and struggled.

In the Deng Xiaoping era there were only two of these factors at work, power and media. In the Jiang Zemin era there were three — power, media and market. And in the Hu Jintao era, technology and citizens were added to the equation.

In the Mao Zedong era before economic reforms, power devoured the media. All of the newspapers were the same, a single voice, and the media were merely tools of despotism. After economic reforms there was a return to some sense of professionalism and notions of autonomy. In the midst of the political reform wave that came in the 1980s there was a corresponding push for press reform.

Media at that time were all Party media. Media were controlled by power, but they sought a level of their own autonomy. Media were often forced by power to utter falsehoods, but they strove to speak truths. This was the game and the struggle that marked the times.

In the spring of 1989, as the pro-democracy movement gathered force, some journalists shouted openly for freedom of speech. There was still no market economy in China at the time, and while experiments in market-oriented media had begun — such as the Economic Weekly in Beijing — these were just delicate green shoots. Some commercial media had begun to appear, like the small tabloids sold at street side, but we were far from having anything resembling a media market.

The market economy in China was something Deng Xiaoping gave his final bursts of energy and influence to achieve. the period immediately following Deng’s “southern tour” was a brief honeymoon period for the media. Those who coveted freedom of speech sprang into action. That period brought the rise of such media as Southern Weekly and Caijing magazine. The two-dimensional structure of power and media became a three-dimensional structure of power-media-market. In his essay, “Democratic Reform Media in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan” (中港台传媒与民主改革的交光互影), Chin-chuan Lee analysed “liberalisation and political control” in detail.

In fact, Jiang Zemin’s phrase “be silent and make a fortune” (闷声发大财) could also be applied to the press policy of the Chinese Communist Party. During that period political power’s relationships and alliances with media and market were equivocal. Of course the Party wanted the media to behave, but it also wanted media to generate profits for them.

In the Jiang Zemin era, crony capitalism developed at a fierce pace. Those who sought freedom of speech used the weapon of marketisation to resist political power, and they discovered that power and the market were often locked in an embrace. Power required the market, the market regarded power with dread, and at times capital was willing to heed power or even work hand-in-hand to control and suppress the media.

But it was in the Jiang Zemin era that a new phantom emerged on the scene, and that was the internet. We can thank our lucky stars that Jiang Zemin did not recognise at the time that the internet would come to haunt China’s leaders. He was supportive of the internet at the time — even though he did not, like Mahatir in Malaysia, announce that there would be no attempt to censor the internet. Of course, it wasn’t until the Hu Jintao era that the internet really began to make its strength felt.

When Hu Jintao came to power in the fall of 2002 the internet was already a lively space, the main platforms being commercial internet news portals, chat rooms and comment sections accompanying news articles. About midway through Hu Juntao’s first term (2002-2007) blogs came on the scene and there was talk about the potential impact of “citizen journalists.”

Many sudden-breaking stories were reported first on the internet by citizens on the ground (internet portals were not permitted to have their own news teams). Corrupt officials we’re often exposed through internet “human flesh searches,” or renrou sousuo (人肉搜索). The internet became a boisterous and diverse space where various opinions could be amplified.

Around the middle of Hu Jintao’s second term (2007-2012) microblogging services emerged on the scene. And at the tail end of his time in office, WeChat came on the scene. More and more people in China were now using the mobile internet — smartphones and tablets. In the past, publishing newspapers, producing radio and television programming, all required high costs. Now the threshold for news production was being pushed lower and lower. The age of “me media” had arrived. Sharing images and video was now easier than ever. This was a subversion and a challenge. It was a challenge to political power and a challenge to capital. The ultimate beneficiaries of information technology were the citizenry.

Over the ten years of Hu Jintao’s rule, civil society developed steadily. This was not thanks to the leadership, of course, but came only through constant struggle by citizens against constant barriers. The interface between civil movements and new media was like a storm cloud moving in, changing the weather in unforeseen ways.

We can already see the changes brought about by this five-dimensional structure of power-media-market-technology-citizen.

Information technology has shaken traditional media such as newspapers and magazines. At the same time, it has created countless new media. In the media marketplace, the internet already reigns supreme. Among internet companies, the big players are the companies listed overseas — the like of Sina and Tencent. In terms of their financial structures, these media are entirely different from Party and government media. The intimate relationship between information technology and the nedia marketplace has already become a major force that cannot be underestimated.

For the traditional media, these are tough times. On the one hand they face strict controls from the press censorship system, and on the other they face stiff and unrelenting competition from new media. Still, there are plenty of journalists of conscience still working in the traditional media. Meanwhile, many professional journalists have migrated from newspapers and magazines to new opportunities to push the bounds and struggle for freedom.

We can expect citizens and civil society to become catalysts for further change. In fighting for their own interests, and for justice and fairness, citizens must struggle also for openness of information and freedom from guilt by expression. Freedom of speech is not just about the rights of the media. It is about the basic rights of all citizens. Many of the people now leading civic organisations and social movements are also major personalities online.

It goes without saying that on the internet at least half of what you see isn’t real. The terrain is chaotic. In our coarse age of sunken values, it’s not a surprise to find unscrupulous media and unscrupulous reporters.

The best balancing factor against poor professional conduct by the media is civil society. Civil society has the potential to demand media act responsibly as they pursue the truth. In fact, more and more journalists in China have become involved in the process of civil society development. Standing together with citizens who seek freedom of expression, experienced journalists who know the terrain well have used the internet to challenge barriers in news coverage. Sometimes they have made advances, and sometimes they have been ruthlessly checked.

The officials in China charged with controlling public opinion are distinctly aware of the challenges they face. In the past 25 years since the June 4th Incident, the market, technology and citizens have compelled political power to change the old system of controls. So far as they are concerned, the most urgent task before them is to turn the immense resources of state capitalism toward the task of both utilising and controlling the media market and information technology, and suppressing civil society. Their hope is to use the market and technologies to advance the Party’s own goals, to strengthen the influence of the Party’s own publications, website and media groups. They reserve the right to purge any voice online, at any time, that they regard as “static” or “noise.” During the second half of 2013, as Xi Jinping spoke, in hardline echoes of the past, of a “public opinion struggle,” the internet entered a period of deepfreeze. Weibo suffered a blow from which it has yet to recover.

Where is the road ahead for freedom of speech? I think, rather than answer this question with talk of optimism or pessimism, of hope or despair, we should answer it with action. We should engage ourselves in those deep changes that are happening right now. These changes could come in many shapes and sizes. They might be changes impelled by social pressure. They might be the product of strife within the political ranks. Or they might be changes actively pursued by those in power (what we called “political system reforms”).

The most decisive changes are likely to come from the market, from technology and from civic action. 2014 is not 1989. Just imagine, if we had the internet at that time, if there had been Twitter and Facebook, Weibo and WeChat, if mature civic organisations like those we have now had existed — would things have happened differently? We doesn’t yield to conjecture. But the future, that is something we can make ourselves.

Over the past 25 years, the road toward freedom of speech has been rough and winding. To be frank about it, we’ve not progressed very far these twenty-five years. But I’ve seen so many journalists, and so many online writers, who have struggled on even as their blogs are “harmonised,” as they’ve suffered abuse or even been detained. They have never given up the fight. They continue to voice their belief in freedom through their actions.

So perhaps the most important question we can ask about achieving freedom of speech, about truly realising the rights to freedom of expression and freedom of the press as guaranteed in Article 35 of China’s Constitution, is: what can we do today?

Thank you, everyone!