At a public signing ceremony two years ago, Duan and his press obtained the Japanese rights to a series of Chinese-language books including The Eastern Battlefield (东方主战场), an edited volume accompanying an official China Central Television documentary commemorating the 70th anniversary of the victory against fascism, and How the CCP Makes Progress — both books published by New World Press (新世界出版社), a division of China International Publishing Group (CIPG), the central-level publisher responsible for the overseas distribution of Party and government publications as part of its overseas propaganda efforts.

The Chinese-language website for Duan Press is full of articles from Xinhua News Agency and the People’s Daily about recent Japanese releases, and interviewing Duan about his work promoting China’s voice in Japan. Duan is apparently getting a lot of attention for its release of Chinese books onto the Japanese market — but this attention is coming almost exclusively from the familiar Chinese state media outfits, which makes this look very much like an inside job.

Russia is another interesting case of apparent self-dealing. At the Beijing International Book Fair (BIBF) in August, a signing ceremony for the foreign editions of Xi Jinping Tells a Story was held in the exhibition area of the People’s Publishing House, and it was announced that the Russian edition of Xi’s book would be published by Chance International Group (尚斯国际集团).

Chance, in fact, was quite active at this year’s BIBF, its general manager, Roman Gerasimov (the guy with the dark beard), attending several signing events at the fair. There was the signing of the deal over Xi Jinping Tells a Story, and with Beijing Publishing House signing of Russian-language rights to In the Name of the People, the book produced from the 55-episode hit propaganda series on the anti-graft drive orchestrated by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (and which television regulators praised as a must-see propaganda flick ahead of this fall’s 19th National Congress of the CCP.) The book was also cited by state media as a bright point of success in the strategy of “going out” for Chinese publishing. Finally, with Joint Publishing, Chance signed a deal for the Russian edition of a book about the Analects by Beijing Normal University professor Yu Dan (于丹).

During the BIBF events, Gerasimov, which Chinese state media variously called editor-in-chief and general manager of “the Russian publisher Chance International Group,” was a visible representative of Russian interest — and no doubt his face, so suitably foreign, was a welcome addition to signing panels advertising the foreign appeal of Chinese books.

But to call Chance a “Russian publisher” is to gloss over a very colorful story — and, as I advertised from the beginning, this piece is about colorful stories.

According to a report from the official China News Service, Chance was created back in 2010 by a retired People’s Liberation Army soldier by the name of Mu Ping (穆平), a native of China’s Shaanxi province. Mu started small, he says, by selling Russian translations of Chinese books overseas. When he found he could make a bit of money this way, he sold off two properties he owned, borrowed a bit, and used this to support his fledgling press. The news report picks up the story:

The transition came in 2013. That year, General Secretary Xi Jinping raised his call for “One Belt, One Road.” Very quickly, as this call deepened in the countries and regions of the Silk Road, demand started for Chinese books just as for Chinese manufacturing, and the market was opened overseas.

At that time, the demand for Chinese books overseas started to increase. Publishing houses back home, says Mu Ping, started seeking them out, and business picked up.

In July 2016, Mu and his Russian publishing company linked up with Zhejiang Publishing United Group (浙江出版联合集团) to open what they advertised as Russia’s first Chinese bookstore, Chance Books (尚斯博库). Mu Ping’s new bookstore was located right in the heart of Moscow, with the goal, he says, of “providing a window on Chinese culture in Russia.”

But this was no ordinary partner. Zhejiang Publishing United Group was an enterprise directly under the Zhejiang provincial government — and from there the crystal stairs led straight up to Beijing, for the top leader of Zhejiang at the time, Party Secretary Xia Baolong (夏宝龙), had served as deputy party secretary in Zhejiang under Xi Jinping from 2003 to 2007 and was regarded as a member of the group of Xi loyalists referred to as the “New Zhijiang Army.”

The opening of Chance Books on July 5, 2016, was to all appearances not just a lively affair, but a very senior one diplomatically. Attending the ribbon-cutting ceremony was Vice-Premier Liu Yandong (刘延东), who has travelled to many countries preaching the virtues of “One Belt, One Road,” and who recently told a gathering in Hungary (English here) that the two sides must “continue to deepen cooperation” in a range of areas, including media and think tank development, “working together to tell our bilateral story of ‘One Belt One Road.'”

Marking what was billed as a landmark occasion for relations between China and Russia in the publishing field, Liu told Sputnik News:

Today is the 20th anniversary of the strategic partnership between China and Russia, and the 15th anniversary of the signing of the Sino-Russian Friendship Treaty. And so, on this day to remember, the opening of the first Chinese bookstore in Russia is also cause for celebration.

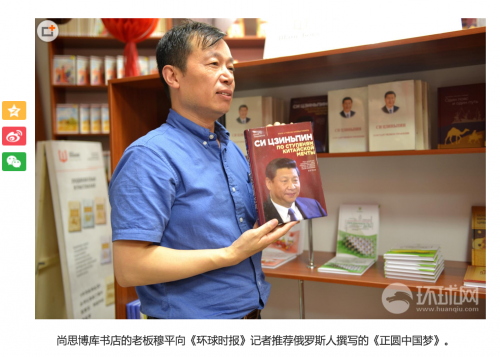

Back in July this year, the Global Times ran a photo profile of Chance founder Mu Ping, giving every impression this was a bootstrap story about a guy who just wanted to open a bookshop, never mind his backing from a powerful state publishing enterprise.

Mu was pictured holding holding up Russian writer Yuri Tavrovsky’s 2015 monograph about Xi Jinping, a book so uncritical in its portrayal that its Chinese-language edition was snatched up by none other than the publishing house run by the CCP’s Central Party School — as was, incidentally, Tavrovsky’s more recent book on “One Belt, One Road.” The shelves behind Mu Ping, meanwhile, were stocked with Russian editions of Xi’s The Governance of China.

Another image in the Global Times profile series showed a promotional placard, in both Russian and Chinese, for Xi Jinping Tells a Story. Appearing also, at least seven weeks ahead of the Beijing International Book Fair, was Mr. Gerasimov, editor-in-chief and general manager — though here, as he was pictured fiddling with the stock, his title was given only as a “salesclerk.”

When I mentioned the story of Chance International Group to a friend from the Czech Republic recently, he was not the least bit surprised. Xi Jinping’s book, he noted, had also been published in his country in what he called a “weird underground manner.”

I suspect that as China’s official story, and Xi Jinping’s copious works, fan out over the “New Silk Road,” there will be many such stories from Xinhua News Agency, China Daily and the Global Times about the “Russian,” “Hungarian” or “Latvian” publishers who have snatched up the publishing rights.

What an interesting fable indeed. And there must, surely, be a moral in there somewhere.