There were no surprises in Xi Jinping’s speech today commemorating the 40th anniversary of “reform and opening” in China. Many observers closely following the live broadcast of the speech on state television were in agreement that its main points closely tracked Xi’s political report to the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party last year. We were basically in familiar territory.

Naturally, one question of great interest to all ahead of this anniversary was whether reforms in China would head in reverse, stall, or advance in some meaningful way.

The purpose of today’s meeting was to commemorate the anniversary of “reform and opening.” Therefore, it shouldn’t surprise us that the phrase “reform and opening,” or gaige kaifang (改革开放) was mentioned 52 times in Xi’s address, or that “socialism with Chinese characteristics” was mentioned 40 times.

There was an abundance of flowery and exaggerated language (10 mentions, for example, for the “great rejuvenation f the Chinese people”). But the speech challenged anyone hoping to find patterns, or to gain any clear sense of direction.

Nevertheless, here are a few observations.

Mao and Deng

When Xi Jinping made an inspection visit to Guangdong in late October, there was no mention whatsoever of Deng Xiaoping in state media reports, a fact that prompted speculation both inside and outside China at the time. So there was a definite degree of nail-biting about how Xi would deal with Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping in commemorating the reform anniversary today.

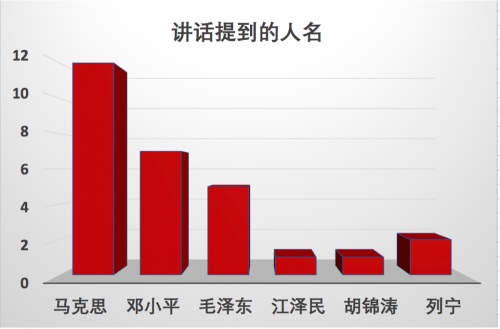

In his speech, Xi Jinping mentioned the names of six people: Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, Marx and Lenin. Here is a graph of total appearances of each in the text of the speech:

When it came to Deng Xiaoping, you could say that Xi Jinping was gracious today. He said:

The 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the CCP was held at a major historical juncture, as the country faced the question of which direction it should head. At that time, the world economy was developing rapidly, and scientific and technological developments were happening constantly, but the ten-year chaos of the “Cultural Revolution” had taken our country’s economy to the brink of collapse, and basic subsistence had become a problem . . . . Inside and outside the Party, there were fierce calls for correction of the errors of the “Cultural Revolution,” so that the Party and the nation could make a spirited new start from the midst of calamity. Comrade Deng Xiaoping pointed out: “If we do not reform now, it will spell the ruin of our projects of modernisation and socialism.”

Under the leadership of Comrade Deng Xiaoping, and with the support of the older generation of revolutionaries, the 3rd Plenary Session of the Party’s 11th Central Committee broke through the fetters of the “left” and its longstanding errors, criticising the “Two Whatevers” (两个凡是) policy [supporting the Mao Zedong line to extremes], fully affirming the necessity of perfecting and accurately grasping the scientific system of Mao Zedong Thought, and offering a lofty assessment of the debate over questions of truth standard (真理标准问题的讨论), firmly ending “taking class struggle as the key link” (以阶级斗争为纲), and determining anew the ideological, political and organisational path of Marxism. From that point, the curtain was opened on reform and opening in our country.

This passage is an affirmation both of Deng and of “reform and opening.” But we should note especially that Xi Jinping has raised here the issue of the errors of the left. Xi has spoken very rarely in opposition to the left. In fact, he has mentioned “the left” (左) in just three speeches since taking office.

The most basic nature of reform since 1978 has been the “reform of Mao” (改毛) — essentially, changing the political line set by Mao. But after Xi Jinping came to power, not only did he avoid criticism of Mao, but in fact he stated that neither the 30 years prior to reforms nor the 30 years since reforms could be rejected. In today’s speech, Xi did not reprise these remarks, but he offered the loftiest of language in praise of Mao, saying that Mao had led the Chinese Communist Party in establishing the People’s Republic of China, and had “established the basic system of socialism, successfully realising the greatest and most profound social transformation in China’s history, setting down the political premise and institutional foundations for all development and progress in contemporary China.”

Xi Jinping characterised the deep tragedy that Mao brought to China as an “exploration” (探索), saying that “in the process of exploration, although [we] experienced serious twists, the Party obtained innovative theoretical fruits and great achievements in socialist revolution and [system] construction, providing precious experience, theoretical preparation and a material foundation for the creation of socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new period.”

There is more harm than good for Xi in raising the banner of Mao. And so he turned next too the fulsome praise of Marx. In today’s speech, many of what I call “deep red words,” or shenhongse ciyu (深红色词语), words like “communism” (共产主义) or like “red” (红色) used as an adjective, did not appear at all. But of all names appearing in the speech, “Marx” occurred with the greatest frequency. “Marxism” (马克思主义) appeared 10 times, and “Marxism-Leninism” (马克思列宁主义) twice.

An Emphasis on Party Authority (党权)

What lesson has China’s process of reform and opening left most indelibly? As Xi Jinping summed it up in today’s speech, the primary lesson of the reform period is that “[we] must adhere to the Party’s leadership of all work” (必须坚持党对一切工作的领导). Xi Jinping exact words were:

The practice of reform and opening has taught us that the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party is the most basic character of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and the greatest advantage of the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics. The Party, the government, the military, the people, the schools, east, west, south and north, the Party leads it all.

This last lengthy phrase, “The Party, the government, the military, the people, the schools, east, west, south and north, the Party leads it all” (党政军民学,东西南北中,党是领导一切的) is language used by Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution — emphasising the unquestionable authority of the Party. In his speech, Xi Jinping said “Chinese Communist Party” 12 times, “our Party” 11 times, and “leadership of the Party” a further 11 times.

Xi Jinping also used a more hardline phrase now rarely seen in the state media, the “Four Basic Principles” (四项基本原则), the third and most core of which is the need to uphold the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. This, said Xi must be “adhered to over the long term, and absolutely not shaken.”

Political Reform, Think Again

In looking back on history, Xi Jinping did use the phrase “political system reforms,” or zhengzhi tizhi gaige (政治体制改革). But there was nothing to suggest political reform as an agenda, a fact that will probably surprise few.

And as for the two figures in China’s history most tied to the question of political reform, and who paid most dearly for its sake, Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) and Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳), Xi’s speech mentioned neither. Zhao has never been rehabilitated, so it isn’t strange not to see him passed over. But Hu Yaobang’s name has been restored, and in 2015 Xi Jinping delivered a speech to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Hu’s birth, speaking highly of his contribution to reform and opening.

The erasure of Hu Yaobang from today’s speech of course touches on the events of June 4, 1989, which are elsewhere eluded to in Xi Jinping’s speech in only in the most oblique way:

Only by fully adhering to the centralised leadership of the Party could we achieve a historic shift, open a new era in reform and opening, and a new path toward the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people, and only in this way could we successfully deal with a series of major risks and challenges, deal with untold dangers and difficulties, calm storms, battle floods, deal with SARS, deal with the [Sichuan] earthquake, transform crisis . . . .

Xi’s reference here to “calming storms,” short for “calming political storms,” or pingxi zhengzhi fengbo (平息政治风波), should be read as a direct reference to June 4, 1989.

But beyond the coolness on the issue of political reform, Xi’s speech today bears a tough and sobering message for intellectuals and those within the Party who might support such an agenda:

We must adhere to the guidance of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era and the spirit of the 19th National Congress of the CCP, strengthening the “Four Confidences” (四个自信) and firmly grasping the forward direction of reform and opening. The question of what to reform and how to reform it must take as its fundamental measure whether it suits the overall goals of improvement and development of the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics and the modernisation of the national governance system and governance capacity. That which should be reformed and can be reformed, we will resolutely reform. That which should not be reformed or cannot be reformed, we will resolutely not reform.

These words may perplex those who are unfamiliar with the political discourse of the Chinese Communist Party. But they essentially mean that political reform in China is off the table. Xi Jinping’s attitude is crystal clear — the Chinese Dream does not include the “dream of political reform” (政改梦).