As I was researching the early stages of reporting on the coronavirus outbreak in China, I came across a number of interesting statements in various official media.

In the People’s Daily on December 16: “Some live animals may carry viruses that, if transported carelessly, could cause the spread of disease.” In the People’s Daily on December 25: “[We] will focus on the prevention and control of major infectious diseases, the handling of public health emergencies . . . revising a number of urgently needed national standards.” In Changjiang Daily, the official mouthpiece of the Wuhan city leadership, on December 17: “Humans feel a sense of triumph over new discoveries and victories in medicine, and so they rest easy, but are unprepared for the approaching epidemic.”

Were these articles on disease and preparedness about Wuhan? No.

The first article was a criticism of the transport of live animals, the second a report on the creation of the new National Technical Committee on Health Quarantine Standardization. The third statement, from Wuhan, came in the context of a book review. All three of these reports used keywords like “disease,” “epidemic” and “public health incident” that seem very of the moment in light of the coronavirus outbreak — but they had nothing whatsoever to do with the epidemic that was at that time spreading silently.

In this article I look back on coverage focusing on four newspapers in particular – the People’s Daily, the official organ of the Chinese Communist Party; Hubei Daily, the official organ of the Hubei provincial CCP leadership; Changjiang Daily, the official organ of the CCP leadership in Wuhan, right at the center of the epidemic; and Chutian Metropolis Daily, a commercial spin-off under the umbrella of Hubei Daily. I focus on the period from January 1, 2020, when media reported that the Wuhan city government had issued a notification on disease cases in Wuhan, and January 26, when media reported on the meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee on prevention and control of the outbreak.

Media Context: A New Year in Politics

Chinese leaders do not pass the New Year and the Chinese Spring Festival in the way that ordinary people do. For them, these events are a political stage for the coming year. And while we have no way of knowing exactly what the Central Propaganda Department specifically planned for its official messaging during this key period, we can glimpse the orientation quite clearly through media coverage itself.

The priorities in in the New Year were all about three major tasks Xi Jinping wished to achieve. First, he hoped to loudly proclaim China’s success in reaching the “full establishment of a moderately wealthy society” (全面建成小康), as some will recall that 2020 was defined back in the 2000s under the Hu-Wen administration as the year that the CCP was to achieve this goal.

This publicity campaign was to be all about China parting ways with poverty once and for all. In line with this, we did see the state media promoting Xi’s “fight against poverty” (脱贫攻坚). Remember that when this “fight” was first declared back in November 2015, it was also linked to the 2020 goal of “moderate wealth,” or xiaokang (小康), with the idea that China’s poor would enter the era of full xiaokang along with the rest of the country.

The achievement of “moderate wealth” and the throwing off of poverty were symbolized in the Party media this month by the figure of Xi Jinping entering the home’s of the people. This has been the central theme of much coverage of Xi’s visits to the countryside in recent years, as in this article looking back on his visits to the Hunan in November 2013 – under the phase, “The General Secretary Visited Hour Home” (总书记来过我们家).

Another apparent objective was to capitalize on Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar in order to re-emphasize the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi’s core foreign policy program.

Finally, the arrival of the Spring Festival period could be used to show Xi Jinping among the people, emphasizing his closeness to them (亲民) and his status – recently emphasized more insistently, since its re-emergence last August – as “people’s leader” (人民领袖). Visits with the military could also be used to stress his status as commander (统帅). And, importantly, a meeting with former top leaders in the Party (including Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao), could be used to demonstrate their commitment to Xi’s leadership and to his governing concepts.

In the following images of the January 1, 2020, editions of the People’s Daily, Hunan Daily, Changjiang Daily and Chutian Metropolis Daily, you can clearly see how the above priorities were played out, with little variation between papers.

These were the frames and campaigns that surely determined in the days and weeks before the coronavirus outbreak emerged as a story that could not be ignored, with clear and urgent public relevance.

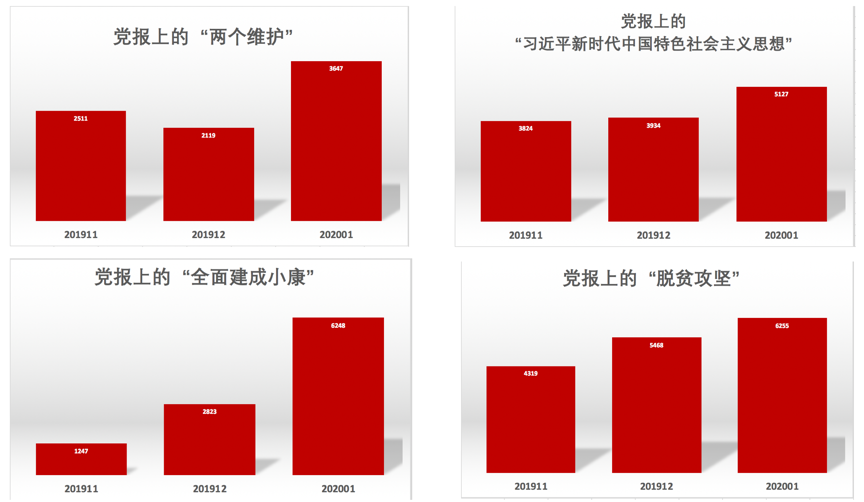

In central and provincial-level Party newspapers, I found a clear shared trend, namely that four political keywords that had experienced the highest level of per-article use in the previous two months (“scalding” on the 5-level scale developed by CMP) had all further risen in intensity.

The first two keywords were the “two protections” (两个维护), meaning to protect the “core“ leadership status of Xi Jinping and the authority of the CCP, and “Xi Jinping thought of socialism with Chinese characteristics for the new era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想), Xi Jinping’s so-called “banner term” (旗帜语). Taken together, the fresh intensity of use of these two terms suggests that propaganda leaders intended to push a new offensive in raising Xi’s status as a “leader”, or lingxiu (领袖).

The phrases “fight against poverty” (脱贫攻坚) and “comprehensive building of a moderate wealth” (全面建成小康) are rooted, as I previously said, in the fact that this year is meant to be the year of achievement of the “moderately wealthy society” in China.

All four of the abovementioned terms can be seen as the core of the January propaganda strategy, all a way to put the focus on the “leader” and his glorious achievements.

It’s an understatement to say that events in Wuhan – and now beyond – have thrown a wrench in these plans. The image below is a headline on page five of the January 1, 2020, edition of Chutian Metropolis Daily, the commercial spin-off of the official Hubei Daily. It reports that a new form of pneumonia has been identified in Wuhan, but says in the subhead that there are “no clear signs of human-to-human transmission.”

Twenty Days in the People’s Daily

From January 1, 2020, through to January 20, 2020, for a full 20 days, not a word appeared in the CCP’s official People’s Daily newspaper about the epidemic in Wuhan. Below you can see all 20 front pages from the newspaper over those days.

All 20 of these People’s Daily editions could be seen as classic examples carrying out the demand for the “two protections,” emphasizing the power and prestige of Xi Jinping. During these 20 days, 19 principle headlines had to do with Xi Jinping. Of these, there are three of his official speeches, three high-level meetings he chaired, two reports of his visits overseas, and so on. There were also four separate reports on the theme of, “The General Secretary Visited My Home,” in keeping with the focus on prosperity and the “moderately wealthy society.”

Together, these 20 front pages included 66 articles in which “Xi Jinping” appeared in the headline.

Things did not change until January 21, when at last news of the epidemic made it into the headlines.

But on this front page, the epidemic is still not the top story. The top story, accompanied by the image, is about Xi Jinping paying a visit to a People’s Liberation Army base in Yunnan.

Local Party Media

From January 1, the day the Wuhan Health Commission (武汉卫健委) issued its notice on the outbreak, to the January 21 edition of the People’s Daily, 20 days had already passed. Under the system governed by the Chinese Communist Party, the Party controls everything (党管一切). And we should remember that the principal readers of Party newspapers – Party members who have subscriptions to various Party papers through their Party organizations – are also the backbone of governance in China.

During this 20-day period, what response did local Party media in Hubei have toward this rapidly spreading disease?

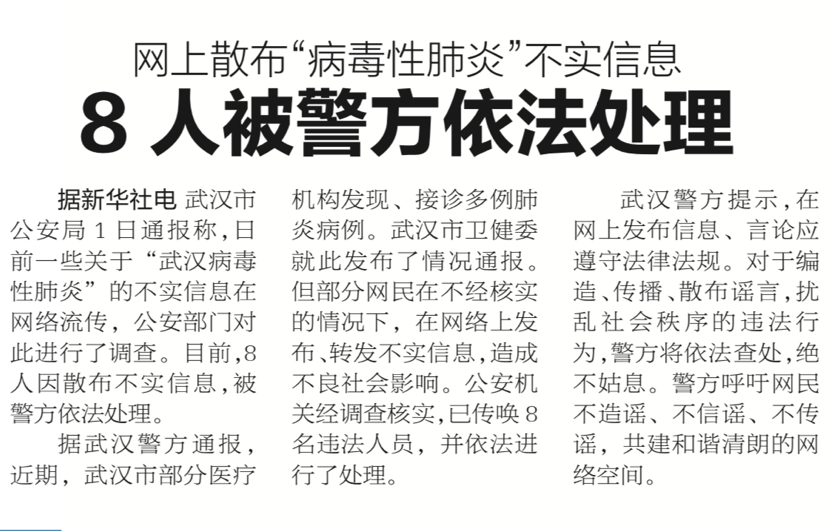

On January 2, Chutian Metropolis Daily reported that eight people had been taken in by the police for spreading inaccurate information about “viral pneumonia” (病毒性肺炎), which had “created harmful social effects.”

On January 6, the same newspaper’s top story on the front page was about tens of thousands of people attending a college admissions event. Another top story was the opening of the local meeting of the people’s congress in Wuhan. A small story just to the right of the masthead was the second notice from the Wuhan Health Commission, saying that SARS and other respiratory illnesses had been ruled out for 59 patient cases.

The happy news in this second Wuhan Health Commission notice was the bell toll that essentially announced that all was well, and the time had come for the festive political atmosphere of the “two meetings” in Wuhan, of the people’s congress and the political consultative conference.

Here are three front pages from Changjiang Daily, the official CCP organ in Wuhan, during the “two meetings.” They follow a pattern rather like the People’s Daily as seen above, focusing on the top provincial leaders and on official news, with some key national Party headlines.

The epidemic was not mentioned at all in the local media while the “two meetings” were in session. There was only a slight mention by Wuhan Mayor Zhou Xianwang (周先旺) in the government’s work report that there was a need to “strengthen the construction of disease prevention and control systems, improving the capacity for emergency treatment and medical treatment in the case of public health emergencies.”

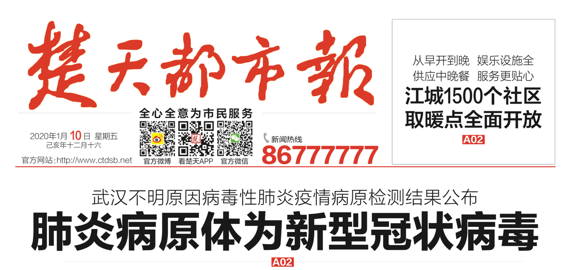

The “two meetings” in Wuhan closed on January 9. The next day, January 10, was an extremely important day in the development of the epidemic. Here is the front page of Chutian Metropolis Daily that day, with a headline reporting that the pneumonia in Wuhan had been identified as a novel coronavirus.

This news, as well as the new notice from the Wuhan Health Commission two days earlier, was entirely ignored by the top Party leadership in Hubei province. The time had now come for the provincial-level people’s congress, and this new “two meetings” season blanketed media coverage.

The “two meetings” of the political consultative conference and the people’s congress opened on January 10 and 11 respectively. In his government work report on January 12, Hubei Governor Wang Xiaodong (王晓东) had a section dealing with key problems, but it made no mention of the epidemic. Another section that dealt specifically with public health talked about the issue in the context of the main propaganda theme of building a “moderately wealthy society.” “Without the health of all the people,” said Wang, “there can be no comprehensively well-off [society].” Again, there was no mention of the illness spreading in Wuhan. Wang’s report talked about “doing everything in our power to continuously enhance the people’s sense of prosperity, happiness, and security.”

It was surely bitter irony for Wang that his report was published in Hubei Daily on January 21, the very same day that Xi Jinping’s high-level instructions on the epidemic made the People’s Daily and media across the country. The obvious gap between the very public, published priorities in Hubei and the direction from Xi was a serious misstep, ironclad proof of error.

But seen from another perspective, Hubei Daily through January was mostly a perfect picture of the servant doing the master’s bidding, and the January 21 paper was simply a rare glint of originality.

If we look back on Hubei Daily frontpages from January 1-20, twenty pages in all, we find that 14 of these are identical to the People’s Daily – essentially just local Hubei versions of the CCP’s flagship newspaper. This is very typical, it must be said, of provincial-level Party newspapers in China since 2013, which have largely lost any of the relative autonomy they might have previously had. Since Xi Jinping’s pronouncement in February 2016 that media must be “surnamed Party,” we have seen the same happen to commercial newspapers as well, so that in the case of Hubei, Chutian Metropolis Daily is also largely a mirror of its “mother paper,” Hubei Daily.

In the midst of this 20-day period there was another bit of news that would in retrospect prove unfortunate for the leadership in Hubei. On January 7, the province’s top leader, Jiang Chaoliang (蒋超良) held a collective study session to address Xi Jinping’s remarks on emergency management. Jiang demanded that officials: “Adhere to bottom line thinking, strengthen risk awareness, strengthen emergency management and emergency capacity building, and resolutely take up the political responsibility to prevent and resolve major security risks. [The Party] must be extremely responsible to the people, do a good job in public health and epidemic prevention, and strengthen open and transparent information disclosure.“

Needless to say, two weeks later, this language would ring hollow.

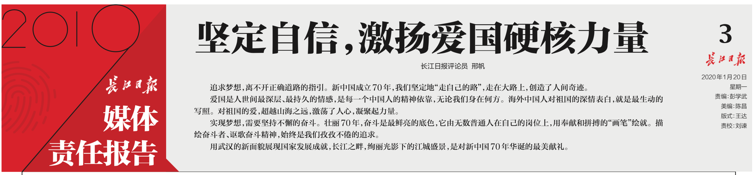

On January 20, shortly before Xi Jinping’s response to the epidemic became public knowledge, Changjiang Daily, the official Party organ in Wuhan, published the results of its “Media Responsibility Report” – this being an exercise now demanded of Party-state affiliated media in China, in which they enumerate their actions, from compliance to innovation. The preface to the report read: “We move with the flow of the people, leaping to wherever the people are. We embrace the internet and set out for the clouds, for the responsibility of the media has never changed . . . .” It added: “The people call, we answer.”

Was this meant to be a joke? Of course not.

As Spring Festival approached, there were no early warnings in Hubei province. The four notices from the Wuhan Health Commission were in each case major news seriously downplayed, reassuring the public that all was well.

On January 17, 18 and 19 in Chutian Metropolis Daily, the mood was celebratory. If people felt fear, it would be impossible to gather them together – and how then to create the impression that all was well?

And so we had villagers gathering to eat dumplings.

We had tens of thousands gathering for a banquet.

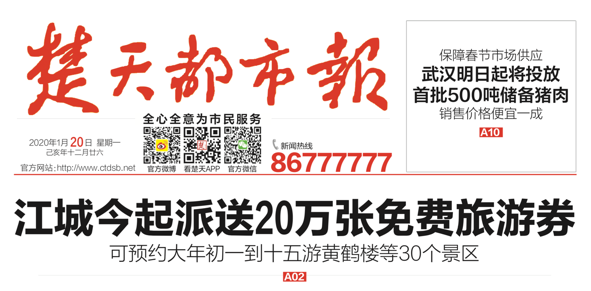

We had the distribution of 200,000 free travel tickets to encourage travel to tourist sights in Wuhan.

But of course all was not well, and the victims of these celebrations, of course, were the people of Wuhan, of Hubei and of the whole country.

Joy and Peace in a Time of Tragedy

On January 21, Xi Jinping made his official remarks on responding to the coronavirus outbreak, which should have meant that the entire country had now entered a period focused on fighting the epidemic. But when we look back on the People’s Daily, we find something that almost beggars belief – the front pages of the CCP’s flagship newspaper on January 22, 23, 24 and 25 have nothing whatsoever to do with the epidemic.

Page layouts are of course also a form of discourse, and an important one in China. Front pages in Party newspapers are a clear representation of the political language and priorities of the Party leadership.

So let’s have a look at what we can see.

Here is the front page on January 22, which leads at the very top with news of Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar on January 17 and 18. After that, with the images, we have Xi in Yunnan province on the 18th, during a time I suppose when he must have issued his instructions concerning the epidemic that resulted in the response on the 20th.

From January 19-21, Xi Jinping was in Yunnan “visiting with cadres and the masses of different ethnicities,” and we have once again the theme – the pre-established theme, you will recall – about “fighting poverty” and “comprehensively building a moderately wealthy society.” Xi was busy visiting among the people, and it was during this time, on January 21, that the first news came of a confirmed case of the coronavirus in the city of Kunming.

While in Yunnan, Xi emphasized the need to “adhere to bottom-line thinking and strengthen risk awareness.” But there was no talk at all of fighting the epidemic.

The front page of the People’s Daily on January 23 reported that Xi Jinping had “met with elderly comrades,” these being former top Party officials, including Hu Jintao and Zhu Rongji.

In what is actually quite a rare practice, this report, meant to demonstrate fealty and trust in Xi’s leadership, actually listed out 111 names of elderly comrades with whom Xi met. It stressed that they “gave a lofty assessment of the historic achievements of the Central Party with Xi Jinping as the core.”

On January 24, on the eve of Chinese New Year, the People’s Daily focused on the Spring Festival celebration for the CCP Central Committee and the State Council.

Xi Jinping delivered what was clearly a very carefully prepared message, calling for “the full building of a well-off society and a determined fight against poverty.” “We must race against time!” he declared. But in that key moment, as an infectious disease was racing against all Chinese, there was no mention at all of the epidemic.

On January 25, there were at last two reports about the epidemic on the right-hand side of the People’s Daily front page. Either of these stories would have merited top billing on the page, but this was not the case. Priority was given instead to a report in the anti-poverty propaganda series, “The General Secretary Visited Hour Home.”

During this key period, from January 21 to 25, many party members, cadres and ordinary people were full of suspicions. They wondered how it was that no member of the CCP Standing Committee had yet managed to visit the scene of the epidemic in Wuhan, something that had happened in the case of both the SARS epidemic and the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. When people felt fearful and at a loss, why was there all this focus on peace and happiness?

The blame certainly does not fall on the shoulders of the top editors of these Party papers. Since the start of the year, the pages of China’s Party newspapers have been given their “assigned seats.” The activities in which leaders would take part had already been fixed, and the themes to be emphasized had been more or less carved in stone. Inspections, greetings, expressions of condolence, banquet speeches – everything had already been planned. There would be no detracting from the prestige of the “leader.”

The system of the CCP is like a great big elephant. It is difficult for the sudden and unexpected to force any change to its huge and lumbering gait.

All of the deception and miscalculation that has happened in the wake of the revealing of the epidemic has been a source of immense public anger. But in such a time of disaster, we have also seen journalists within the system trying to act in good conscience, and internet users too have taken to new digital platforms to try to raise their voices.

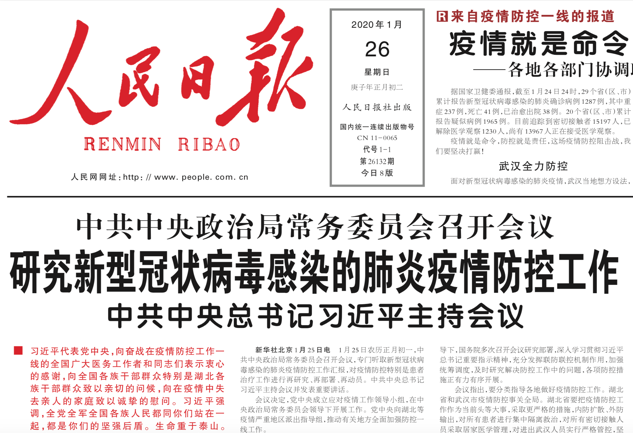

Since January 26, as media across China reported on the meeting of the Standing Committee to address the epidemic the day before, as seen above, China has at last entered true epidemic response mode.

From this point on, we can expect the Party media to begin playing a slightly different game. Let us watch and see.