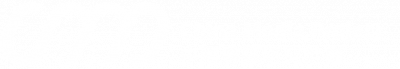

On Wednesday, one of China’s largest tea chains found itself at the center of an online storm after a video emerged of employees for the company apparently wearing cardboard signs and makeshift cardboard handcuffs to enforce workplace discipline — public displays of shame that had disturbing echoes of the country’s political past.

The offending post, made on September 17 to the official Douyin and Xiaohongshu accounts of the Guangdong operations of Good Me (古茗茶饮) — a tea chain with more than 5,000 locations across the country — showed several employees on site at a Good Me shop standing with their heads cast down, their hands bound in front with what appeared to be cardboard cup holders. Handwritten signs around their necks read: “The crime of forgetting to include a straw”; and “The crime of knocking over the teapot.”

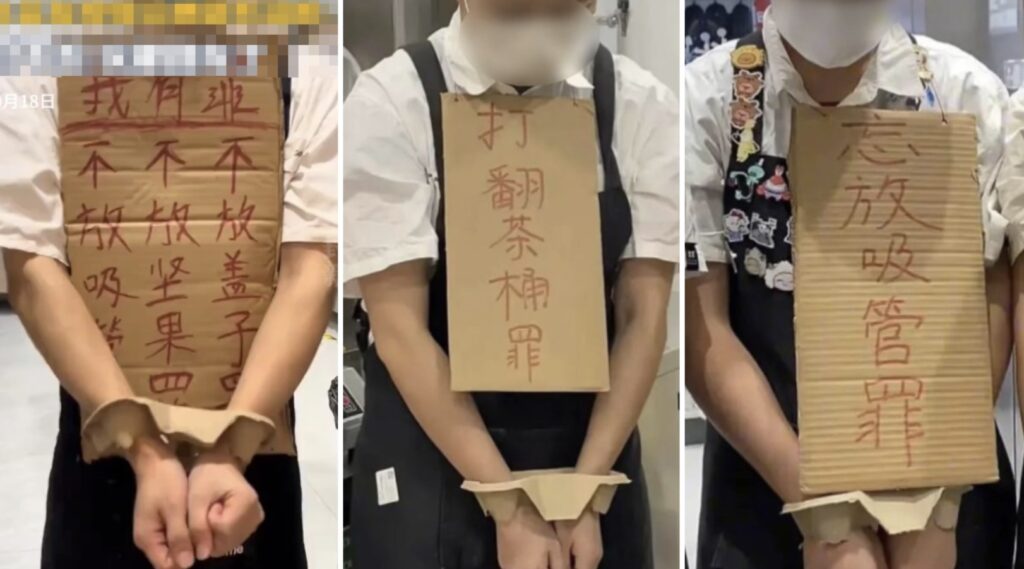

The meme the Good Me account seemed to be riffing on was not a contemporary, social media derived one, but rather an extremely painful episode from China’s past. In the midst of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, millions of Chinese branded as “class enemies” were persecuted in brutal public spectacles known as “struggle sessions” (批斗大会). In many cases, they had their heads shaved, and were forced to wear dunce caps and signs identifying their supposed crimes as they were subjected to physical and verbal attacks by crazed mobs.

For China’s media and internet authorities, the Cultural Revolution is generally not a subject to be talked about at all. And for many Chinese who remember the period, which was ended by the ouster and arrest in October 1976 of the so-called Gang of Four, it remains a silent source of pain and fear.

In other words — not funny.

The post quickly went viral, but for all the wrong reasons. Most comments on the video on both platforms expressed shock and ridicule at what seemed to be extremely unfair and inhumane treatment of employees on the one hand, and an acute lack of good taste on the other. By Wednesday the video had been removed and Good Me was scrambling to contain the damage.

According to a report from Shanghai’s The Paper, the incident involved the company’s branch in Shenzhen’s Longhua district, where an employee involved in the filming said it was intended as a joke, and that the three employees in the video had volunteered to take part. The employee said the branch did not punish employees for small mistakes like forgetting straws.

On Wednesday afternoon, Good Me issued a public apology through its Weibo account. “We’re sorry,” it said. “We were playing with punchlines, and it went all wrong.”

The term here for “playing with punchlines,” wan’geng (玩梗), has become a popular video content form in the digital media space, essentially referring to humorous posts spawned by existing memes circulating on social media. The form, familiar to any regular user of social media in any language today, has given rise to millions of humorous videos on China’s mobile internet — but also, from time to time, stern warnings from state-run media. In February 2022, the People’s Tribune, a journal published by the CCP’s official People’s Daily newspaper, warned that society must be mindful of “the deviations in value orientation brought about by playing with punchlines.”

“We were playing with punchlines, and it went all wrong.”

Apology from Good Me Tea.

The apology from Good Me further explained that the video from the employees had attempted to riff on a recently popular punchline meme about “double-cup handcuffs” (双杯杯托手铐). “We thought it was funny, but it brought misunderstanding and unease to some netizens,” said the company. “After receiving feedback from netizens, we took down the video at the first available moment.”

Internet users responding to the apology, numbering more than 60,000 by noon Thursday, remained mostly unmoved. Some called on the company to make a public apology directly to the employees, while others suggested a video apology would be more appropriate. For most, it was reminder of the pitfalls of jumping on the video humor bandwagon.

“If you play with punchlines, you must be careful,” wrote one user in a comment under the company’s apology. “You’ll definitely learn your lesson now.”