Chen Weijun’s (陈为军) 2001 documentary (released 2003) on Chinese AIDS villages, “To Live is Better Than to Die”, can now be shown in mainland China, bringing to an end a four-year ban, the film’s director confirmed by phone Wednesday. Mr. Chen said film was now available on DVD in stores across China, but there were likely to be few public showings.

“I’m very happy about this, of course,” Chen told CMP. “A lot of people in China have wanted to see this film for a long time but have never had the opportunity.”

Copies of “To Live is Better Than to Die” have been available in stores across China since late March, Chen said.

Chen Weijun began shooting his AIDS documentary in the summer of 2001, after he was introduced to five AIDS patients in Wuhan by doctor Gui Xi’en (桂希恩), credited as the first doctor to document China’s AIDS villages. Breaking from his day job with a local Wuhan TV station, Chen traveled to the Henan village of Wenlou and, disguised as a farmer, filmed a Chinese family’s struggle with AIDS without the knowledge of local officials. Chen’s documentary was banned by Chinese authorities, but received critical acclaim outside China, winning a Peabody Award in 2003.

The availability of Chen’s film within China could be seen to signal a further relaxing of restrictions on coverage of the country’s HIV-AIDS crisis, which was first exposed at great risk by domestic media in 1999-2000 and taken international by The New York Times in October 2000. Recent contributions include Wang Keqin’s excellent China Economic Times report to commemorate International Aids Day last year.

Chen’s film should be regarded as an important example in what has been called China’s New Documentary Movement (新纪录片运动) — generally speaking, films produced independent of the government using inexpensive digital video technology. News that the film is now unshackled in China offers a good opportunity to address some recent misunderstandings about this documentary movement and its importance.

In an entry called “Wu Wenguang’s Village Video Project”, one blogger recently had the following to say about new Chinese documentaries:

Before seeing the films produced by Wu Wenguang and the villagers, I had spent a couple days watching other documentary films made by contemporary Chinese filmmakers. In a sense, these filmmakers were capitalizing on the new capabilities offered by DV cams. Whereas filmmakers once had to conserve film because expensive reels of tape restricted their ability to shoot long, continuous takes, DV filmmakers can just keep the camera running and then pick and choose the bits that are most compelling.

What this generally translates into is an extremely long (one might say boring) documentation of some aspect of modern life in China that is spiritually empty. Most of the documentaries produced in China today seem to belong to an artistic movement called the “New Documentary Movement” (新纪录运动). Wu Wenguang is considered an early member of this movement, and all of the other films I saw were considered part of the movement as well.

Before seeing the films produced by the villagers, one thing really struck me about these New Documentary Movement films. While they were interesting in a cultural sense, they were incredibly tedious and difficult to follow. Not one of them contained a narrator, and only once did text appear on the screen describing the action that was happening in the film. People were talking to each other, and conversations were painstakingly stiched together, one after another, on the presumption that the audience would be able to grasp what was happening in the lives of the people who were on film. The approach is artistic and tasteful, but not very entertaining or brave. I would surmise that the absence of narrative, which is so widespread, indicates that the New Documentary Movement filmmakers are of two stripes. One is your average loyal party member. The other is too frightened to make a judgement and lead his audience.

To criticize these New Documentary films for lacking narrative devices or the courage to “lead” the audience is to miss the point entirely. These films, as expert Lu Xinyu (呂新雨) of Fudan University and others have noted at length, represent a break with documentary tradition in China precisely because they do not lead the narrative or impose the voice of the narrator. Here is Lu Xinyu in her book Documenting China, contrasting the new documentary with the state-produced “special topic films” (专题片)) of tradition:

Special topic films are done by national television; they are a kind of “social responsibility” undertaken by the national television station, a manifestation of the national ideology. They take a top-to-bottom look at Chinese society. Documentaries, however, must probe from another perspective. I often use the metaphor that the dominant ideology is the sun that illuminates whatever it touches, but a normal society must also have moonlight, starlight and lamplight. Documentaries are an important complement to the dominant ideology; they enable non-dominant (非主流) people and marginal groups to write their own existence into history.

Given the tradition of state-imposed ideology and its rigorous enforcement in the media via the cardinal principle of “guidance of public opinion” (舆论导向), it should not be hard to understand the director’s interest in letting his or her sources speak for themselves. Quite contrary to the speculation that the new documentary creator must be a “loyal party member”, it is this lack of guided-ness that gives these films their decidedly non-Party character.

One documentary filmmaker recently told the author, in fact, that he conceived of himself more as a journalist than an artist. He felt new documentaries, while presently having little direct social or political impact, will in future prove important first drafts for a non-official history of contemporary China.

Chen Weijun’s documentary, an intimate look at the lives of Chinese AIDS patients on which Party ideologies do not intrude, is a clear case supporting such a role for these films.

There doesn’t yet seem to be much writing online about the release of “To Live is Better Than to Die” (and there are apparently no Chinese media reports, except one in Hong Kong’s Apple Daily on May 23), but here is what one mainland blogger wrote about the film after seeing it last month:

Yesterday I saw the documentary film, “To Live is Better than to Die”. My heart is so cold I can’t breathe. Faced with setbacks and difficulties, everyone thinks of death, thinks of escape. Death, in such situations, is a kind of beguilement — a form of extrication.

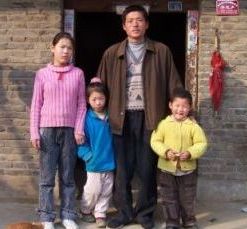

This film tells the story of a family beset with HIV-AIDS. A father, mother and three children. The father faces not only the agony of his illness and the approach of death, but must witness the creeping illness of his loved ones. He has thought of death, but must not die. He knows that by throwing off his own pain he would leave even greater tragedy for the others.

I so admire his resoluteness. He bears his own pain, determined not to add it to the pain of those he loves … What a responsible man this is, a great man! A father and a husband. Surely, heaven will send angels to great him …

[2003 coverage of Chen by Time magazine]

[Site on Independent Documentary book]

[Discussion on independent documentary with Zhi Ruikun]

For Chinese-language readers we also strongly recommend reading Dong Yueling’s (董月玲) 2004 coverage of “To Live is Better Than to Die”, which was featured in the Freezing Point supplement to China Youth Daily even while the ban was in force. Her story, which narrates the story of the Ma’s and of Chen’s film, begins:

Wuhan TV’s Chen Weijun never himself expected that the documentary he made with his DV camera, a film about the ordinary lives of a peasant family, would shake people to their cores and bring him international acclaim.

In Wuhan, I climb to the seventh floor of an apartment block, dripping with perspiration as I approach the Chen home. In the disorder of the sitting room, I watch this documentary, “To Live is Better Than to Die”. After I’ve watched the 80-minutes, my feet and hands are icy. I struggle for breath.

Chen Weijun never ceases smoking. When he’s finished with the cigarettes in the box and on the end table, he harvests the butts from the ashtray, carefully tears each open, rolls up another and smokes again …

[UPDATE:Chen’s film seems to have been shown at a film festival in Anhui Province on April 19]

[Posted by David Bandurski, May 24, 2006, 6:16pm]