Last week China’s 21st Century Business Herald reported that information industry officials had tasked a “Weblog research group” with exploring the creation of an identification system for the country’s blogging population, requiring all users to register with their real names. The news drew anger from commercial media and Internet users, sparking a debate over privacy, anonymity and freedom of expression.

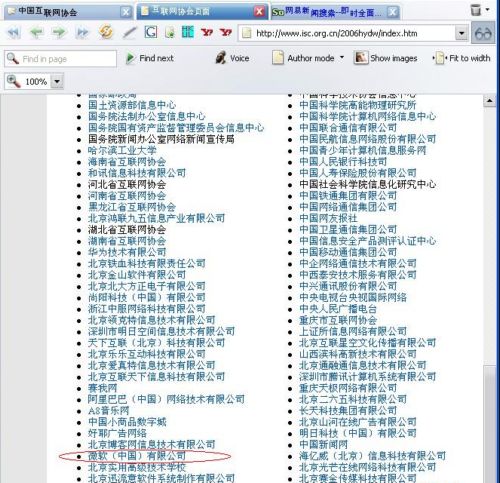

21st Century Business Herald cited a source on October 19 as saying that the Ministry of Information Industry had asked the Internet Society of China, an association of Internet industry companies under the thumb of Internet ministers (the same group that issued a self-censorship contract earlier this year), to address six Internet “agenda items”, including the scope of a “blog identification system” (博客实名制) like that recently implemented for mobile phones in China. The association formed the “Weblog research group” on August 2, with representation from 13 Internet companies including, said Youth Daily (Shanghai), people.com.cn, Qianlong, Sina.com, Sohu.com and Netease. Microsoft, which operates its MSN Spaces blog service in China, is also a member of the Internet Society of China and listed on the group’s Website [BBC on alleged Microsoft self-censorship of blogs]. Other US Internet companies, including Yahoo!, have been criticized by human rights advocates for cooperating with the efforts of the Internet Society of China. One topic of skepticism among Chinese media and Internet users has been the nature of this organization and what right it has to make decisions touching on the rights of hundreds of thousands of Internet users in China.

[ABOVE: Microsoft (China) listed among members of the Internet Society of China]

The next day, October 20, criticisms of the proposed identification system started coming from commercial media in China, reminiscent of other recent public policy-related rallies, including that against China’s draft emergency response law and Internet regulations in Chongqing.

Zhu Sipei (朱四倍) wrote in the New Express that officials were resorting to identification systems as a kind of crude last “straw to clutch at”, as though by implementing such systems in all areas of society they could solve public management issues with one stroke.

Zhu attributed the use of identification systems to an entrenched “paternalism” in the government, or the notion that leaders must check personal freedoms for the good of the people. The writer refered to the theories of economist Janos Kornai [JSTOR paper 01][JSTOR paper 02][Elena Lankova on paternalism and state socialism]:

I believe the fact that identification systems have become popular forms of management underscores a cultural and technical predicament. Speaking to deeper causes, paternalism is an important reason for the birth of these identification systems.

In China, ‘Managing you for your own good’ (管你,是为你好) is a manifestation of the government’s paternalism. From our tradition of father-mother officials [local magistrates] to comprehensive support under the planned economy, we have always been accustomed in our hearts to being citizen-children (子民), yearning for and receiving the care of the government. Under the market economy, the government’s direct participation in the economy has lessened, but intrusion and control and surveillance are a common occurrence. This kind of parental attitude can be glimpsed everywhere in government control and surveillance actions. But does our society need this kind of paternalistic logic?

It can be said that as identification systems encroach on public rights and benefits they have no way of gaining the people’s respect. If a system is does not have the consent and trust of the public, not only does it have no way of gaining legitimacy, it will carry enormous social costs. Paternalistic logic makes clear to all that identification systems face the prospect of failure [abortion] even before they are born.

An editorial in yesterday’s Southern Metropolis Daily questioned the nature of the Internet Society of China and why it had the power to “trample” on the speech freedoms of Internet users.

According to reports, the government is kicking around the idea of a “blog identification system”. Some say it’s “already decided”, others say it’s not yet been approved. But amidst a furor of opposition online Yang Junzuo, secretary of the “Internet Society of China” and the “Self-Discipline Work Committee”, has already said that “rolling out an identification system for blogs does not merit fear of what influence it will have”.

Freedom of expression is no doubt relative, but what we’re seeing here is: an association whose nature we do not understand, and a committee whose nature we likewise don’t know, can without reservation trample on the speech freedoms of all Chinese bloggers.

This Secretary Yang says: We cannot speak rashly and say unreasonable things simply because of Internet freedom.

Speaking rashly is not doubt a bad thing; before we speak we should moderate what we are going to say. But again what we’re seeing here is: an association whose nature we do not understand, and a committee whose nature we likewise don’t know, can presume to teach us what is reasonable.

The editorial’s tone is angry, and concludes with the bitterly sarcastic suggestion China simply shut down the Web altogether:

Therefore, I advocate completely blocking off the Internet, even to the point of cancelling all Weblogs and the Internet – then we can be sure we don’t have any of this “unreasonable” online behavior. Come to think of it, even if China doesn’t have an Internet, I really think we should continue to preserve, or even expand, the “Internet Society of China”, preserving and honoring the grand contributions these two secretaries (we could raise it to 20 secretaries) have done for freedom, control and surveillance, reason and order.

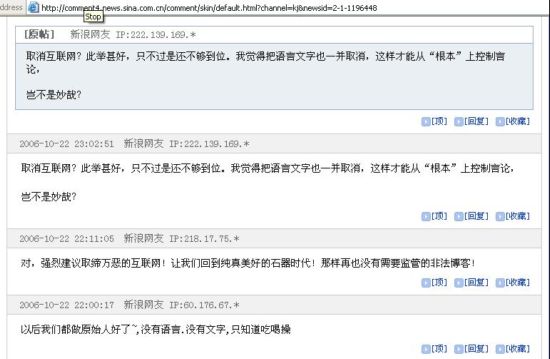

Web postings to the Southern Metropolis Daily editorial at Sina.com grabbed the sarcastic tone with gusto:

Yeah. I wholeheartedly agree with putting a lid on the Web! Let’s return to that great and pure age of stone tablets! Then we’ll never again have to get a handle on these illegal blogs!

——-

Cancelling the Web? This is a good idea, but it doesn’t really go far enough. I think we should should cancel words and language altogether. Only in this way can we control speech “at the roots”.

Huaxi Metropolis Daily quoted on industry insider yesterday as saying: “There’s no telling what kind of influence this thing could have on the market”.

Yangcheng Evening News wrote in an editorial that “responsible freedom” could come only when citizens’ rights and benefits were protected:

That ‘freedom is relative’ is not wrong, and it’s also correct to say that ‘only responsible freedom is healthy freedom’. But the condition has to be that freedom is preserved – only when there is a freedom in which rights and benefits are guaranteed thoroughly by the law does the possibility of abuse of that freedom arise . . .

Wanting to pass a blog identification system to make people take responsibility for their expression is a false problem. Only when freedoms are guaranteed does the question of “abusing freedom” arise. Only when there is freedom of expression can we talk about self-restraint . . .

—————–

[ON “identification” and “anonymity”]

Beijing Youth Daily

Basic Reasons for Identification and Anonymity

October 16, 2006

The news that an identification system (实名制) [“real-name system”] will be in place for mobile phones by year’s end has lately brought a great deal of discussion.

From going online to making a bank deposit or buying a mobile phone – the news and appeals have not stopped in recent years. Within this discussion the question of anonymity is often seen as a person’s right (权利) and the identification system is portrayed as meaning responsibility and duty. So as soon as one raises the question of identification systems, people can’t help but be sensitive to the question of rights – on the Web, this is sensitivity about the freedom to express oneself (自由表达权); when we make bank deposits or buy mobile phones, it’s a concern about our own privacy. All of these [concerns] are reasonable.

But what are the basic reasons for employing anonymity or identification? I’m afraid [to answer] this requires going back and considering the issue of rights and responsibilities between people and basic human logic and sensibilities.

Both anonymity and identification concern the social relationship between people. Different principles apply to various levels of society.

First of all, public and private are different levels. Public affairs and private affairs are also different levels. A person’s expression concerning public affairs constitutes public opinion (舆论). It should not be subject to “forced identification” (强制实名), just as is the case with street-side conversation which cannot be subjected to forced identification.

But if a person’s speech is directed at one individual this does not constitute “public”, but rather a connection between one individual and another individual. In such cases the speaker should be identified, whether online or offline. But when a particular person goes online and at one instance addresses the public and in the next instance addresses an individual, how do we determine the issues of anonymity versus identification? This is a conundrum present only on the Web. In my view, the first thought should be with protecting their right to public expression, and afterwards with his civil responsibility as an individual. Actually, in the event that there is no identification and the rights of another are intruded upon, it is possible to obtain evidence about the identity [of the anonymous person in question] through technical means. As, for example, in recent cases of online defamation.

Unlike public anonymity, our contacts and existences as individuals are generally all identified, whether it be national hukou registration (ID cards), marriage licenses or interactions among friends, relatives or colleagues. We interact as identified and recognized friends and colleagues – including by telephone; we also use real names to make contact with various government offices, registering for this or that permit.

On the personal level identification is the principle and condition under which we ordinarily accept interaction. If you don’t know a person’s name or surname, you don’t invite them to your home. We cross paths with innumerable people on the streets but don’t ask each for their name. But if you have an interaction with someone, you want to know their name . . .

But why is it that when you purchase something in an ordinary situation no one demands your identification? When you buy a tube of toothpaste the shop doesn’t have any reason to demand you prove your identity. This is because this interaction is not between two individuals, but only an exchange of objects (a product for money). When two individuals interact identification is required because these individuals must take responsibility in the interaction; for money and things there is no need for identification and knowing names, only for exchange according to an agreed-upon price.

Well then, why does using the telephone require registration? This is not a simple exchange between buyer and seller . . . but a question of long-term service, and this service assumes such relationships as credit, and in the credit relationship an interpersonal relationship is subsumed in the exchange of goods for money . . . The telephone is fundamentally different from the Internet in the sense that it is basically a tool for interpersonal communication, and not a tool of public expression (the two are best not confused). . . .

Of course, it’s understandable that people want to remain anonymous to protect their privacy and avoid being sold out by businesses, because the protection offered by anonymity is simply reliable judging from present circumstances. But taking a more long-term view, many of our rights should not rely on anonymity for their protection, because the vast majority of social interactions and social events cannot go on anonymously. It is therefore necessary to build a system that protects both the right to privacy and the right to expression, including a system for seeking responsibility in cases where rights are violated. We cannot simply rely negatively on anonymity.

[Posted by David Bandurski, October 23, 2006, 6:00pm]