By David Bandurski — “There is a new Cultural Revolution taking place in 21st century China, and it is a lot healthier than the old,” former British prime minister Tony Blair wrote in the Wall Street Journal a couple of months back. Films, art, fashion and pop music are “thriving” in China, said Blair, who apparently observed this cultural ferment during a tour of Guiyang back in August.

Blair’s argument about the “health” of social and cultural change in China is difficult to refute. After all, how can we possibly not concur that the slow simmer of change we see in China today is “healthier” than the brutal, decade-long political upheaval of the Cultural Revolution?

Come to think of it, a lot of things are “healthier” than violent political persecution. But where exactly is this new “cultural revolution” Blair is talking about?

[ABOVE: Jiangxi’s top leader, Su Rong, speaks at a recent conference on “cultural sector reform.” See below.]

As I read Blair’s editorial, I pictured the faces of a lot of active artists, journalists and filmmakers who, to me anyway, epitomize China’s cultural vitality. All of them share the distinction of being shut outside the CCP’s political “mainstream,” where creative space is walled in by narrow political and ideological demands.

The week before Blair declared a “new Cultural Revolution” in China, I was in New York for the premiere of Ghost Town, a documentary film that — like all independent films from China, unsanctioned by government authorities — can be shown on the mainland only in limited unofficial forums, where it can fly under the radar.

Just as Blair was making his declaration, renowned journalist and CMP fellow Dai Qing was making her way to the Frankfurt Book Fair, and Chinese authorities were doing everything in their power to ensure she could not attend.

Culture is still subject to rigid controls in China. The most vibrant cultural activity goes on in the margins, in that strange grey space between the cracks of official control. And much of this activity is permitted to go on precisely because it has been so effectively sidelined by the authorities that it is not perceived as a threat.

Films made without official approval are effectively prevented from broader distribution inside China. Nonfiction works like CMP fellow Yang Jisheng’s Tombstone, a breakthrough two-volume investigation into the great famine of the late 1950s and early 1960s, can find an outlet only in neighboring Hong Kong.

China’s creative potential is marvelously rich.

But let us take a realistic look at how China’s leaders talk about the role of culture, its development and control — without resorting to worthless apple-and-orange comparisons spanning four decades.

I’m going to take a stab in the dark here and suppose that as Blair toured China at summer’s end, the term “cultural reform” was hanging on the tongues of his official hosts. That would make sense, because the term “cultural sector reform,” or wenhua tizhi gaige (文化体制改革), has been an important part of the official lexicon in the news and propaganda sphere for years now.

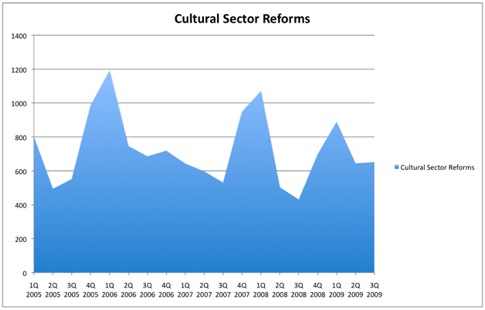

[ABOVE: Occurrence by number of articles of the term “cultural sector reforms” in mainland Chinese media. Source: Wisenews.]

What Chinese officials are essentially talking about is the commercial development of the “cultural sector.” The focus is on maintaining strict political control over cultural messages while building culture as a force of economic growth.

But don’t take my word for it.

Earlier this week, a provincial conference on cultural reform opened in Jiangxi’s capital city of Nanchang. Jiangxi’s top leader, Su Rong (苏荣), spoke about “revitalizing the cultural sector,” but at the same time made it patently clear that political controls would be maintained in order to ensure “harmony and stability.”

Specifically, Su emphasized in his closing remarks that the party would firmly maintain “decision-making power over major projects, control over asset allocation, [and] final power of approval over propaganda and cultural content.”

Then came the political bottom line:

[We must] ensure that the principle of party control over ideology does not change, party control over the media does not change, party control over cadres [appointments, etc.] does not change, and correct guidance of public opinion does not change.

Su’s words may invigorate propaganda leaders. They probably will not resonate with creative spirits.

News of Su Rong’s speech from official Jiangxi media follows:

Provincial Conference on Cultural Industry Reform and Cultural Industry Work Opens — Chairman Su Rong Gives an Address

On December 15, [Jiangxi’s] Provincial Conference on Cultural Industry Reform and Cultural Industry Work opened in Nanchang. Provincial party secretary Su Rong (苏荣) emphasized that in order to unswervingly promote cultural sector reforms and thoroughly revitalize the cultural sector in our province, [we] must cleave to a correct cultural development direction throughout, must endeavor to build systems and mechanisms that benefit and liberate the development of cultural productivity, must seize the opportunity to realize striding development in our province’s cultural sector, and must work hard to create the combined strength necessary to promote cultural sector reforms.

Provincial party committee standing committee member and provincial propaganda minister Liu Shangyang (刘上洋) led the conference and discussed concrete strategic measures for cultural sector reforms and cultural sector development. Provincial people’s congress vice-chairman Wei Xiaoqin (魏小琴), provincial consultative congress vice-chairman Chen Anzhong (陈安众) also attended the conference. Vice-governor Sun Gangzuo (孙刚作) gave a summary speech.

Cultural Products Must Be Enjoyable to the Masses

Deepening cultural sector reforms is a matter that concerns national cultural security and concerns the harmony and stability of society.

“Quintessential cultural products (文化精品) must be enjoyable to the masses, otherwise they are not cultural products but rather tributes.” This was Su Rong’s classic definition of quintessential cultural products (文化精品). Culture, Su Rong said, combines industrial and ideological attributes. Deepening cultural sector reforms concerns national cultural security and concerns the harmony and stability of society. Any reform and development measure must, [said Su], benefit the consolidation and strengthening of Marxism’s leading position in the ideological sphere, must benefit the adherence to the correct guiding principles of service to the people and service to socialism, and must benefit the carrying forward of the socialist core value system . . . making culture glow with powerful vitality, attraction and appeal.

Using the Best System and Mechanisms

If we remain fettered by tradition and walk over our own footsteps, then we will be eliminated from the competition and be cast aside by the times.

Su Rong said that in deepening cultural sector reforms, innovating systems and mechanisms was most key. If the system had vitality, there would be vitality overall. If mechanism were new, then the aspect [of culture] would be new. Whatever system was good, whatever mechanisms were effective, those systems and mechanisms should be used, so long as they benefit the glorious development of socialist culture.

Experience has shown that only be staunchly liberating thought and renewing systems and mechanisms can cultural enterprises and the cultural sector find the road ahead and have vitality. If we remain fettered by tradition and walk over our own footsteps, then we will be eliminated from the competition and be cast aside by the times . . .

[We] must, in accordance with the overall demands of the central party on pilot tasks in cultural sector reforms by end-of-year 2010, foster cultural market entities that are up to standard, must apply our efforts to asset restructuring for for-profit cultural units, and must build up backbone cultural enterprises . . . [A list of broad strategic goals here] . . . [We must] create a modern cultural market system . . .

The Rise of Guangxi is Inseparable from the Revitalization of the Cultural Sector

Fostering the cultural sector as a core strategic, backbone sector in our province, moving quickly to implement a development plan for cultural sector development.

“The history of a nation or a region is ultimately a cultural history,” Su Rong said. Looking at the development of culture through history, Su said, even in periods of economic crisis or slump, culture often reverses the trend and emerges as a force driving the rapid rise of the cultural sector and the ushering in of a golden age. We must seize the opportunity and stay abreast of the times.

While the cultural sector in our province has made major advancements lately, we still fall behind in comparison to a number of developed regions. It should be said that the support of the cultural sector is vital to Jiangxi’s development, and that Jiangxi’s rise is inseparable from this revitalization of [the province’s] cultural sector . . .

Su Rong emphasized that cultural sector reforms are a complicated systematic social project, and that the scale of reforms, their rate of progress, their level of effectiveness, relied on the energetic support of party and government entities at all levels, and on the support and cooperation of relevant departments. [We] must, [he said], firmly grasp throughout the decision-making power over major projects, control over asset allocation, final power of approval over propaganda and cultural content, the power over appointment and approval of key leaders and cadres, ensuring that the principle of party control over ideology does not change, party control over the media does not change, party control over cadres [appointments, etc.] does not change, and correct guidance of public opinion does not change.

[Posted by David Bandurski, December 17, 2009, 1:27pm HK]