A whole new set of terms is emerging in China to describe the country’s growing national power. Taken together, these form what might be called a “discourse of greatness,” or shengshi huayu (盛世话语). China’s discourse of greatness includes such terms as “China in ascendance” (盛世中国), “the China path” (中国道路), “the China experience” (中国经验), “the China pace” (中国速度), “the China miracle” (中国奇迹), “the rise of China” (中国崛起) and, last but not least, the “China Model” (中国模式).

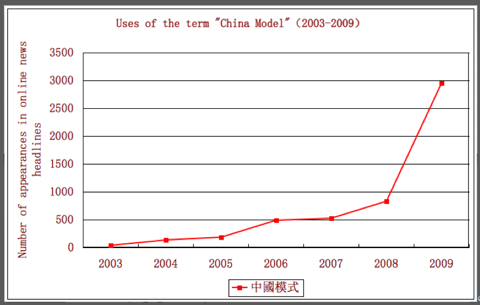

Using China’s domestic Baidu search engine to track use of the term “China Model” over the past few years, we can clearly see the upward trend.

In the past, China and the CCP have suffered bitterly at the hands of their own “models.”

As economic reforms were just starting out in the early 1980s, economist Xue Muqiao (薛暮桥) wrote in the official People’s Daily newspaper that China’s planned economy, the “iron rice bowl,” had been fashioned on the Soviet Model (People’s Daily, October 13, 1980, p. 5).

In 1988, then People’s Daily editor-in-chief and reformer Hu Jiwei (胡绩伟) and Chang Dalin (常大林) again emphasized the roots of the old CCP model as they urged political reforms in People’s Daily: “In terms of its system, [reforms mean] carrying out necessary reforms and improvements to the socialist system built by the Chinese Communist Party on the basis of Marxism-Leninism and the Soviet Model” (People’s Daily, December 30, 1988).

In 1982, Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) raised the concept of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” (中国特色的社会主义) at the 12th National Party Congress. This term, which has been used ever since, was originally employed by reformist CCP leaders as a term of compromise to contend with more conservative, leftist elements in the party. It essentially took the bottle of “socialism,” which conservatives in the party still staunchly defended, with the new wine of reform.

The characteristics of this reform became gradually clearer through the 1980s. Economic reforms meant progress toward a market economy. Political reforms meant progress toward democratic politics (民主政治).

After the June 4th crackdown of 1989, as Deng Xiaoping strove to protect and uphold the banner of reform, the slogan “socialism with Chinese characteristics” was sustained, but its meaning underwent a mutation.

In 1991, the term “China Model” appeared for the first time in People’s Daily. It had its origins, apparently, in praise of China from some unspecified commentators in Romania (People’s Daily, October 29, 1991). The Berlin wall had fallen. The Soviet Union and socialism in Eastern Europe had all but disintegrated. And yet, China avoided the collapse many Westerners had supposed would come. China took another path, promoting capitalism on the economic front while maintaining a tight CCP monopoly on power.

This path of political tightening and economic opening became the “Chinese characteristics” that many people spoke about — and it was, some said, the envy of the Third World. Those who voiced praise for China and its “China Model” included Benin parliamentary member Adrien Houngbedji (1994) and former Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda (1997).

Commemorating the twentieth anniversary of economic reforms in 1998, People’s Daily wrote that “when you search the four corners of the earth, you find that the prospects here [in China] are particularly fine. International public opinion has accoladed China’s development path, and the fruitfulness and effectiveness of the ‘China model'” (People’s Daily, November 22, 1998).

After President Hu Jintao took office in 2002, the term “China’s rise” swept China. If “China’s rise” is a verdict on China’s accomplishments, the “China model” is a summary and description of China’s experiences and their supposed applicability outside China.

In 2004, American Joshua Cooper Ramo http://joshuaramo.com/ promoted the idea of the “Beijing Consensus” in a pamphlet (download here) first written for the Foreign Policy Centre in London.

In his paper, Ramo postulated a “Beijing Consensus” against what he called the “widely-discredited” Washington Consensus, “made famous in the 1990s for its prescriptive, Washington-knows-best approach to telling other nations how to run themselves.” Ramo also referred to the “China model,” or “Beijing model,” of development, and argued for its attractiveness to the rest of the world.

Chatter about the “China Model” really took off in China in 2008 and 2009. We started seeing headlines like these in the Chinese media. “It is the time to establish the China Model.” “The dominance of the China Model.” “The China Model as a preserver of human rights.” “Viewing the China Model through the troubles in Eastern Europe.” “Russian scholars believe the China Model benefits the whole of humankind.” “American scholar: the success of the China Model shames the West.”

An official Xinhua News Agency commentary on the occasion of Chinese National Day last year suggested that the global financial crisis marked the ascendance of the “China Model.”

At this time, plagued with the global economic crisis, the world economy faces a low point such as has not been seen in decades. Meanwhile, in the east of the world, socialist China is as ever maintaining a relatively high-level of economic development.

Four events in particular backgrounded the sudden rise of the idea of the “China Model” in China in 2008 and 2009. First, there was China’s hosting of the Olympic Games in 2008. Second, there was the thirtieth anniversary of economic reforms in late 2008. Third, in 2009, there was the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. And, finally, there was the global financial crisis.

At the end of last year, the Central Compilation and Translation Press published a book called The China System: Reading 60 Years of the People’s Republic of China (中国模式: 解读人民共和国的60年). As the book’s editor, Pan Wei (潘维), , the director of Peking University’s Center for Chinese and Global Affairs, explained to China’s Oriental Outlook magazine:

The economic model of the ‘China model’ has four pillars: state control of land and of the raw materials of production; a state-run model for the financial industry and large-scale enterprises; a free labor market; free commodity and assets markets. The political model [of the China model] has four pillars: the democratic concepts of modern democracy; an emphasis on the passing by officials of selection and evaluation mechanisms; an advanced, selfless and united ruling group; effective mechanisms of government division of labor, error-correction and checks and balances.

Pan believes that “breaking through the superstition surrounding [democratic] elections is an urgent task of the intellectual and political elite in our country,” and that China has not collapsed “precisely because it resisted the system of multi-party elections promoted by the West.”

Fang Ning (房宁), head of the Political Science School of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, writes in the The China System that “carrying out this sort of development model requires a relatively centralized system.” The institutional secret of China’s rise, he says, “is that one-time authorization [of political power] lowers the cost of decision-making.” What he is suggesting is that the Chinese Communist Party’s sixty-year hold on power has been an extension of a one-time authorization [of political power] that took place back in 1949.

China’s leadership elites have generally maintained a subtle and noncommittal attitude toward the idea of a “China Model.” While Li Changchun (李长春), the politburo standing committee member in charge of ideology, and propaganda chief Liu Yunshan (刘云山) have both used the term before (in fact, the discourse of greatness is itself a product of their national image and propaganda strategy of “grabbing the discourse power” and “expanding influence”), President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao have never used the term in formal remarks.

A number of Chinese intellectuals take a critical attitude toward the use of the “China model” and other such vocabularies of glory. They call for a more honest account of China’s problems and its crises, for a more direct look at the many and various reasons for China’s rapid economic growth and a number of “secrets” that must not be overlooked.

Tsinghua University professor Qin Hui (秦晖) said to Guangdong’s Window on the South magazine in 2008:

Aside from the traditional advantages of low wages and low welfare burdens [because basic services like education and healthcare are not provided to the workforce], China has used the ‘advantage’ of ‘low human rights’ (低人权) to suppress human, land and capital costs as well as the price of non-renewable resources. By preventing bargaining, and by limiting or even canceling many transaction rights, [China has] ‘reduced transaction costs’. By suppressing participation, disregarding ideas, conscience and justice, and by stirring people’s minds to pursue mirages of material prosperity, [China has] achieved a level of competitiveness that is frightening to all countries, whether they are free-market nations or welfare nations. Moreover, nations on the democratic path, whether they are making progressive steps or employing ‘shock therapy,’ have all been left behind.

In September 2008, Ding Xueliang (丁学良), a professor at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, wrote a piece on the Chinese-language website of the Financial Times called, “Why the ‘China Model’ is difficult to promote” (“中国模式”为何不好推广?). In it, Ding argued persuasively that China had paid a massive social cost for its rapid economic growth, including the destruction of the environment and a severe failure of social justice.

Professor Ding said the Beijing Olympic Games had shown off both the frightening achievements and the frightening costs of the “China Model.” “Many nations of the world have the economic means to hold an Olympics on such a scale, but they do not wish to because they believe there are other areas where money might be spent more productively,” Ding wrote.

Earlier this month, Yuan Weishi (袁伟时), a professor at Guangzhou’s Sun Yat-sen University, voiced his doubts in an interview with Hong Kong Commercial Daily about whether a “China Model” had actually taken shape at all. Yuan said China was now entering a period of sharpening social tensions, and that once problems of subsistence had been resolved people would begin to express greater demands for the protection of their rights. Such social tensions could only be resolved, he said, through democracy and rule of law.

Scholar Wu Jiaxiang (吴稼祥) wrote on his blog recently that China’s model under economic reforms has been one of market economy + authoritarianism (市场经济加威权政治). To understand an abstracted China Model as a replacement for freedom and democracy, he wrote, amounted to “using honeyed words to get others to smoke opium and experiment with recreational drugs.”

Perhaps the most interesting dissenting views of all came on December 27, 2009, in the official CCP journal Study Times (学习时报), published by the Central Party School. Study Times ran four essays urging caution over the “China Model.” The writers of these pieces included former State Council Information Office head Zhao Qizheng (赵启正) and Li Junru (李君如), vice president of the Central Party School.

Stay tuned. In the future ups and downs of China’s discourse of greatness, we might find clues to changes in China’s political climate.

[Posted by David Bandurski, February 23, 2010, 2:10pm HK]

[Frontpage image by Matthew Stinson available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.]