China has come down hard on domestic social media platforms this week, disabling comment functions on major platforms like Sina Weibo and QQ Weibo for a period of 72 hours ending tomorrow, April 3, at 8am.

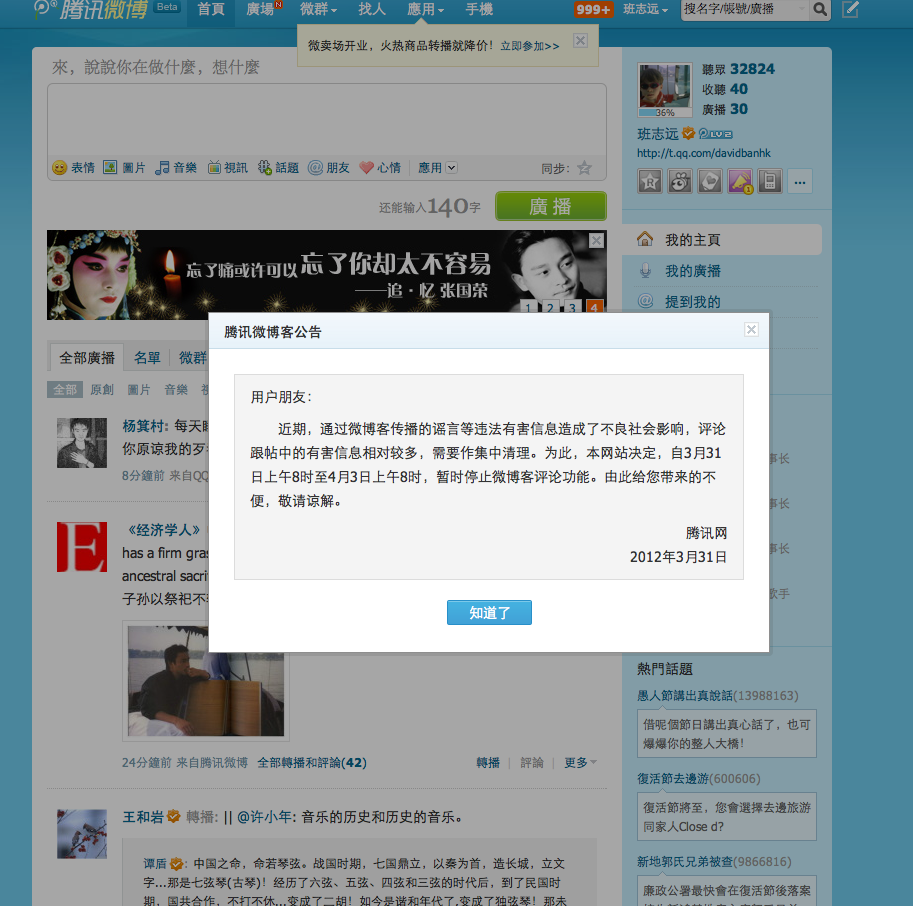

While comment functions seemed to have been disabled without explanation by Sina, users of the Weibo service at QQ were greeted with the following message notifying them of the ban.

Users and Friends:

Recently, rumors and other illegal and harmful information spread through microblogs have had a negative social impact, and harmful information has been relatively predominant in comment sections, requiring concentrated cleansing. For this purpose, this site has decided to temporarily suspend the comment function on microblogs from 8am March 31 to 8am April 3. We express our apologies for any inconvenience.

Tencent

March 31, 2012

The Tencent announcement suggests this was a decision undertaken by the service itself, but this is undoubtedly an action taken by the central leadership through the agency of the State Internet Information Office (国家互联网信息办公室).

The catalyzing incident seems to have been rumors on and after March 20 of a coup attempt in Beijing, but the campaign against “rumors”, which has intensified since August 2011, in fact signals a broader tightening of China’s stance on social media.

We won’t repeat our past arguments here about the bogus nature of the anti-rumor campaign, and its feigned interest in truth and accuracy when in fact the underlying principal is the political control of information. Here are seven different CMP pieces dealing with “rumors”, press control policies and social media since August last year:

1. “China tackles the messy world of microblogs” — August 11, 2011

2. “Busting the bias of the rumor busters” — August 12, 2011

3. “Control, the soil that nurtures rumor” — August 15, 2011

4. “Big oops leaves state media red-faced” — August 16, 2011

5.”Why do rumors explode in China?” — September 27, 2011

6. “Rumor Fever” (International Herald Tribune) — December 12, 2011

7. “In China, the bats of rumor take wing” — March 22, 2012

In particular, we encourage readers to revisit “Control, the soil that nurtures rumor“, written by CMP fellow and Peking University professor Hu Yong, one of China’s leading experts on social media.

Adding grist to the conversation, we include this translation of an editorial run yesterday by the official Xinhua News Agency:

“[We] Must Firmly Say ‘No’ to Rumor Spreaders“

April 1, 2012

Xinhua News Agency

Relevant [government] departments have released the results of an investigation into recent online rumors and have detained 6 suspects according to the law for fabricating rumors, and carried out education and censure on others who broadcast related rumors online. The response online has been positive, with web users saying “those who fabricate or spread rumors are detestable, and they should be punished.” There has also been debate. Some have said that “those who fabricate rumors should be punished, but those who spread rumors should be dealt with leniently.” Immediately some people shot back, “It’s true that the fabricators of rumors are detestable, but those who spread rumors are just as disreputable.”

I support the latter view.

Spreading rumors is about following along. . . The fabricators of rumors are the source, those who follow along in spreading rumors boost them, making rumors spread far and wide.

One characteristic of those who follow rumors is that they enjoy idle reports, and they take things too literally. The smallest thing, a few isolated words or phrases, are amplified and built up layer after layer by the rumor transmitters, until in the end they become major events, just like the saying that “the smallest deviation can result in the widest divergence” (失之毫厘,谬之千里).

According to online media, the rumor of “gunshots fired in Beijing” that spread around this time originated with the dialogue written by a certain writer for a television program: “The sound of gunfire, and tomorrow it will be major news.” This was posted to his own microblog. And this empty sentence was subjected to the limitless guesswork of well-meaning people who made up their own versions until it became, “Gunshots fired in Beijing, something major has happened.”

It so happens there is a precedent. A few months back, media revealed that relevant [government] departments had investigated a number of classic cases of online rumors: a certain military affairs website editor saw a post with a couplet that read, “An iron bird in the radiance of the setting sun, a puff of blue smoke,” and cobbled together the random remarks of web users to suggest the explosive news that, “The air force has lost an airplane.” This information was then widely spread about by some overseas media which enjoy the “heady taste” of rumors, having an extreme negative impact.

This rumor and the rumors of gunshots in Beijing are so much alike in how they were concocted! So to a large extent, those who pass along rumors are also rumor fabricators.

. . .

Rumor fabricators and rumor spreaders have one thing in common, and that is a weak concept of the law. In the public opinion space of the internet everyone has the right to post speech online, but everyone must take responsibility for what they say. Whether it means fabricating rumors or spreading rumors, “finding amusement” in this important matter of social safety and stability is not only an expression of irresponsibility toward oneself and one’s society, it is extremely damaging.

In other countries of the world too such behavior will not be tolerated. Not long ago some media reported that two British youth planned a trip to the United States, and before they went one posted on the American microblog site Twitter that he would “blow Los Angeles to the ground” and would “dig up Marilyn Monroe.” [NOTE: the British would-be tourist, Leigh Van Bryan, actually wrote: ““Free this week for a quick gossip/prep before I go and destroy America?” Bryan wrote to Twitter user @MelissaxWalton. “3 weeks today, we’re totally in LA p—ing people off on Hollywood Blvd and diggin’ Marilyn Monroe up!”].

As a result the two were detained by American authorities at the Los Angeles International Airport. While the two insisted it was all just a joke, they were still detained for 17 hours and send back to their home country the next day. Should the masses of web users not find this incident enlightening?

To sum up, following along in passing on rumors is undesirable. Fabricating rumors is illegal, and passing rumors on is just as illegal.

[Frontpage photo: Chinese flee from the specter of “rumor fabrication” in this February 2012 cartoon published in the official Shanxi Daily newspaper.]