One of the key strategies of China’s Party leadership in enforcing media controls — under the information policy mandate of “public opinion guidance“, or yulun daoxiang (舆论导向) — has been to restrict the source of news production. This is why the Party prevents online news portals from reporting news independently, forcing them to rely instead on the aggregation of news reported by traditional media, including China’s new generation of market-driven newspapers.

Web portals operated by companies like Sina, Sohu and Tencent cannot maintain their own teams of news reporters. That’s why comedian Zhao Benshan (赵本山) committed a major comic faux pas back in 2010 when when he played out a routine for the annual Spring Festival on China Central Television in which ordinary peasants in the countryside were interviewed by a pair of men introducing themselves as “online journalists” working for a fictional Sohu.com program called “Seeking the Root of the Matter” (刨根问底).

[ABOVE: Comedian Zhao Benshan (second from left) is interviewed by fictional “online journalists” during a skit for the official 2010 Spring Festival Gala.]

As though to fire home the point that reporting restrictions for online media were no laughing matter, the General Administration of Press and Publications (GAPP) — the government agency that licenses journalists and publications — reiterated on February 22, 2010, that websites in China were not eligible for press cards, and therefore had no right to carry out interviews or gather news.

The word in Chinese is caifang (采访), which can mean “interview,” “report” or, more broadly, “gather information.” The GAPP official said websites, or anyone without proper press accreditation, had no “right to interview,” or caifangquan (采访权).

Restricting the “right to interview” to traditional media is politically safer because magazines and newspapers, whether Party run or market-driven, are all part of the official press genealogy. Even market-driven newspapers must have “sponsoring institutions,” which help to ensure political discipline. [For more background on this, please read our post: “How Chinese media relate to power“].

Commercial web portals, which are situated outside the extended Party press family, cannot be trusted with the precious “right to report.”

However, as we’ve emphasized again and again, confusion and complexity are the order of the day in China’s media environment. Just as traditional media — and particularly commercial publications — have exploited the gaps in order to push news coverage further, so have commercial websites tested the limits.

One of the best recent examples of this is Tencent’s Living (活着) series, which manages to offer quality investigative news in pictorial form.

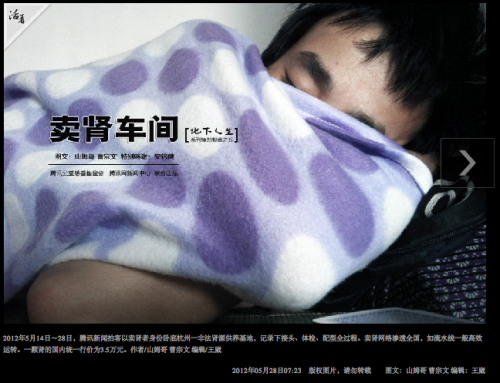

On May 28, Living ran an investigative photo series about China’s national network of illegal kidney suppliers.

We encourage readers to visit the series themselves, but we offer a taste below of how it begins, slide by slide. Brother Sam (山姆哥), incidentally, is the alias for a well-known Chinese investigative reporter, about which we will say no more.

SLIDE 1

From May 14 to 28, 2012, Tencent news photographers went undercover to an illegal kidney sourcing facility in Hangzhou posing as individuals wanting to sell their kidneys, recording the entire process . . . The kidney sales network extends across the country, operating as an efficient assembly line. The price for a single kidney domestically is 35,000 yuan. By Brother Sam (山姆哥) and Cao Zongwen (曹宗文), Editor Wang Wei (王崴)

[ABOVE: The opening slide of QQ.com’s photo report on China’s national kidney sales network. The story’s lead is shown below the photograph..]

SLIDE 2

The kidney selling location in this undercover investigation is located at the intersection of Linding Road (临丁路) and Tiandu Road (天都路) in Hangzhou’s Jianggan District (江干区). From the outside things look perfectly normal, and no one would ever guess that here lives a group of young people who hope to sell their own kidneys. Every year in China the lives of close to one million people rely on dialysis; but in the past year, legal kidney transplant procedures numbered only 4,000. The massive demand has led to the emergence of underground kidney donation, and built up an illegal network of explosive profits.

[ABOVE: Young Chinese wait in a Hangzhou facility, where they hope to sell their kidneys for 35,000 yuan. .]

Continue reading the story from Tencent’s Living (活着) series HERE.