By QIAN GANG

Keywords: The Four Basic Principles and Mao Zedong Thought (四项基本原则/毛泽东思想)

What political trends can we expect to unfold during the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, a once-in-a-decade leadership transition that will set the tone for China’s domestic political environment for years to come? Will political reform cower in the wings, barely visible? Or will it stride out to center stage?

Certainly, China’s political battles are complicated affairs, waged largely behind the scenes, backstage, between flesh-and-blood Party leaders with their own, competing agendas and ideological proclivities. But the language of China’s Party politics, the script that emerges as “consensus” from this backstage melee, can offer us important clues to emerging trends, as well as to the strength of regressive political impulses. China’s political script is rewritten every five years, taking shape in the “political report” delivered at each National Congress.

On the question of political reform, there is one important terminology in particular we should remain alert to if we hope to read, between the lines as it were, the larger political climate of the 18th National Congress: the “Four Basic Principles,” or sixiang jiben yuanze (四项基本原则).

[ABOVE: The site in Shanghai where the Party’s 1st National Congress was held in 1921, by Peter Verkhovensky posted to Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.]

If this term continues to appear in the political report to the 18th National Congress, it is possible to say with some certainty that, barring shifts of a more dramatic nature, there is little hope or expectation for substantive political reform. By the same token, a strong showing in the political report for this buzzword would signal an unfortunate turnabout, a backsliding, on the issue of political reform. But the vanishing of the term altogether would be the most important signpost for political reform.

So where does this term, the “Four Basic Principles,” come from? And what does it mean?

On March 30, 1979, Deng Xiaoping marked out the boundaries for a process of reform that had just begun. He said:

First, we must adhere to the socialist path; second, we must adhere to a dictatorship of the proletariat; third, we must adhere to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party; fourth, we must adhere to Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought.

In the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping’s “Four Basic Principles” formed the very heart of China’s political orthodoxy. However, they later became the most effective tool by which those on China’s extreme political left opposed Deng’s policy of reform and opening. Deng Xiaoping’s political line in the 1980s was referred to also as the “third plenary political line” (established, that is, during the third plenary session of the 11th National Congress, held in 1978).

[ABOVE: A propaganda poster for the “Four Basic Principles” posted to China’s internet.]

In the ideological struggles that marked the first half of the 1980s, General Secretary Hu Yaobang, a strong advocate of economic and political reform, was sharply criticized by the chief proponents of the left for contravening the Four Basic Principles. Hu was eventually forced to resign his position as General Secretary, opponents claiming his light-handed approach had contributed to public demonstrations in 1987 calling for greater economic and political liberalization. Two years later, it was again the truncheon of the Four Basic Principles that leftists wielded to force the resignation of Hu Yaobang’s successor, Zhao Ziyang, in the aftermath of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Incident. As a result, Deng Xiaoping lost a capable ally.

Hu and Zhao were both conscientious actors for political reform. But as the veteran Xinhua News Agency reporter Yang Jisheng wrote in his chronicle of that time, Political Struggle in the Era of Reform: “The first issue to be resolved in terms of political reform is checks and balances on power. Checks and balances on power would mean upsetting the current leadership system. In both cases, the removal of these general secretaries was prompted by [the struggle over] political reform. In the conflict between the Four Basic Principles and political reform, there was no room at all for either of them to maneuver.”

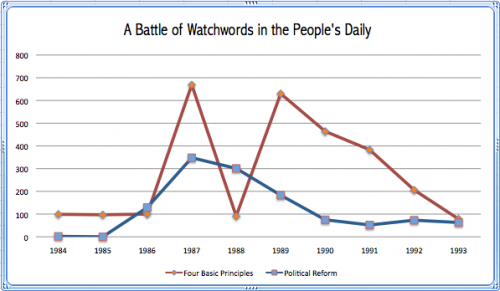

These two terms, the “Four Basic Principles” and “political system reforms” – the more drawn out term in Chinese for political reform – were locked in fierce opposition throughout the 1980s. In the Party’s official mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, we can still glimpse the fossil evidence of this tension.

In 1988, when the political reform movement was reaching its zenith, the Four Basic Principles were in rapid retreat, as can be seen from the graph above, which plots occurrences of each term in the People’s Daily over time. In 1989 the situation was reversed. But we can also see that by the 1990s both terms were in decline, political reform bottoming out by 1990, and the Four Basic Principles joining it at the bottom in 1993, by which time the country was preoccupied with an unprecedented economic acceleration.

In China’s media today the Four Basic Principles occur with very low frequency. In the 10 years since President Hu Jintao came to power, the term has appeared in headlines in the People’s Daily on just three occasions – in 2004, 2007 and 2008.

The last instance came as the Party commemorated the 30th anniversary of China’s policy of economic reform and opening. The second instance came as the newspaper unpacked President Hu Jintao’s political report to the 17th National Congress of the CCP in 2007, in which he mentioned the Four Basic Principles.

But the most important case by far was the first one, in 2004. This was the handiwork of one of the most prominent members of China’s Maoist faction, Chen Kuiyuan (陈奎元), the head of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Commemorating the centennial of Deng Xiaoping’s birth that year, on August 22, Chen Kuiyuan remarked: “The adherence to the Four Basic Principles is one of Deng Xiaoping’s greatest contributions to the socialist cause.” In a clever stroke of leftist spin, Chen was suggesting that the greatest legacy of the man who has been called the architect of China’s economic rise, was not reform, but in fact the political orthodoxy of the Four Basic Principles.

[ABOVE: The People’s Daily runs an article by Chen Kuiyuan in which he says the Four Basic Principles were Deng Xiaoping’s greatest contribution to the socialist cause.]

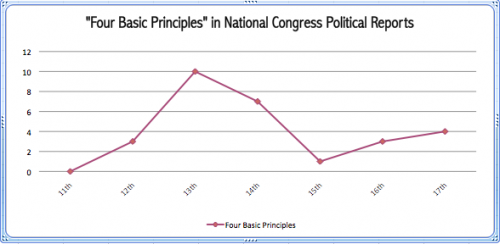

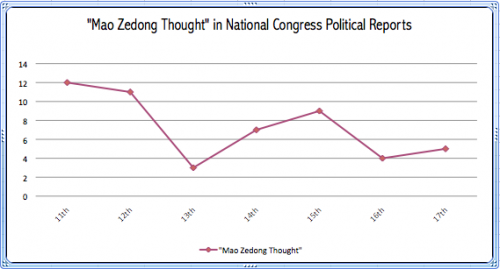

Here is how the term Four Basic Principles has played out in successive political reports from the 11th National Congress in 1977 to the 17th National Congress in 2007:

The 13th National Congress in 1987 was the meeting at which political reform became a part of the agenda. But Hu Yaobang’s resignation had come at the beginning of that year, and his successor, Zhao Ziyang, had to waver his way across a political tightrope. He did not dare shortchange the Four Basic Principles and risk drawing fire from his political opponents. So the term peaked just as political reform was in its inception as an issue.

The term came up just once in President Jiang Zemin’s report to the 15th National Congress in 1997, as a nod of acknowledgement, but without particular emphasis. One question remains: why, in President Hu Jintao’s report to the 17th National Congress in 2007, did usage of the Four Basic Principles surpass both of the previous political reports, those in 1997 and 2002?

In fact, the Chinese Communist Party long ago scrapped the first two of the Four Basic Principles. China would “adhere to the socialist path,” said Deng Xiaoping. But in no respect is “socialism” in China today similar to socialism as Party leaders would have understood it when Deng uttered these principles in 1979. Before the opening and reform policy was initiated, China’s economic system was a system of Soviet-style planning combined with Mao Zedong-style command economics. By the standards of the day, today’s China would no doubt be regarded as having taken the capitalist road.

In the second of his Four Basic Principles, Deng Xiaoping said China would “adhere to the dictatorship of the proletariat.” But this idea has, not unlike the original notion of socialism, become something of an anachronism with the Party. It has virtually disappeared from use, except in rare instances where it is raised as a matter of historical fact. The last use of the term “dictatorship of the proletariat” as a matter of current relevance in the official People’s Daily newspaper, in fact, was the August 2004 article by Chen Kuiyuan, the same one I alluded to above.

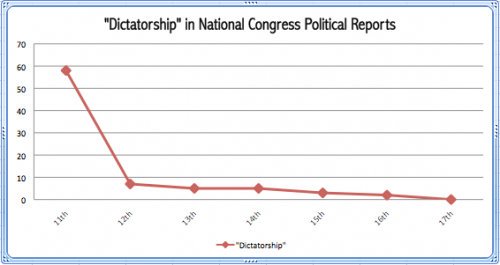

The current term of favor, replacing “dictatorship of the proletariat,” is “people’s democratic dictatorship,” or renmin minzhu zhuanzheng. And even this term is something of a rarity these days. Here I have graphed the frequency of the use of the term “dictatorship” in successive political reports.

As readers can readily see, use of the term “dictatorship” fell dramatically after the 11th National Congress, held in August 1977, and has declined ever since.

Of the remaining two of Deng Xiaoping’s Four Basic Principles, the “leadership of the Chinese Communist Party” remains unshaken and unchanged. The last, “Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought,” is a matter for further study and scrutiny. In particular, “Mao Zedong Thought,” this deep-red expression, is like a terminological zombie, dead in one sense but in another refusing to die, vested with so much political baggage that it still haunts China’s politics. Clearly, for many Party chieftains this term continues to have utility.

The term Mao Zedong Thought originated with the Party’s 7th National Congress in 1945. In 1956, as the Communist International criticized the cult of personality in which the former Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had enveloped himself, it seemed untimely to harp on the political philosophy of China’s own personal dictator; Mao Zedong Thought was dropped at the 8th National Congress in September 1956. But after the Lushan Conference in 1959, the term resurfaced in the People’s Daily. This marked a direct and concerted campaign to preserve Mao’s moral and political authority following the calamities of the Great Leap Forward and the Great Chinese Famine.

Under the direction of Marshal Lin Biao, the People’s Liberation Army took the vanguard in “holding high the great red banner of Mao Zedong Thought.” Before the onset of the Cultural Revolution, the term was already running hot in the Party newspapers. During the Cultural Revolution, the term blazed hotter than the sun in the sky, and more than a few lives were scorched by this ideological weapon, jailed and even killed for “opposing Mao Zedong Thought.”

After the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese Communist Party cautiously questioned and redressed the errors of Mao Zedong. Many of the most integral aspects of Mao Zedong Thought — the people’s communes, class struggle, continuing revolution — were scrapped. But the hardened shell of Mao Zedong Thought stubbornly remained, venerated by some. Here is how the term has fared from the 11th National Congress in 1977 to the 17th National Congress in 2007:

During the 11th and 12th National Congresses in 1977 and 1982 respectively, Mao Zedong Thought continued to make a strong showing. But as the political reform agenda was kick-started at the 13th National Congress in 1987, the term sank to an historic low. For Maoists within the Party, the chaos that followed the bloody crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in Beijing on June 4, 1989, was an opportunity to restore their leftist agenda; the term Mao Zedong Thought made a comeback in the 1990s, rising steadily through to the 15th National Congress in 1997. In 2002, as he handed the presidency over to Hu Jintao, Jiang Zemin tried to shift China’s politics to the right, and Mao Zedong Thought was played down somewhat in that year’s political report. Five years later, in Hu Jintao’s report to the 17th National Congress, the term trended upward yet again.

The uptick of Mao Zedong Thought in the 2007 political report might have been dismissed as incidental. But there were other signs too. In 2009, a mass military procession, full of pomp and pageantry, was planned to commemorate the Party’s 60th anniversary. Initially, there were to be three major parade groups eulogizing the Party leaders of the reform era — Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Three days before the celebrations, however, a fourth “Mao Zedong Thought parade column” was added to the mix. For those awaiting a renewed political reform agenda, the sudden appearance of this parade column was like a thunder roll, signaling stormy days ahead.

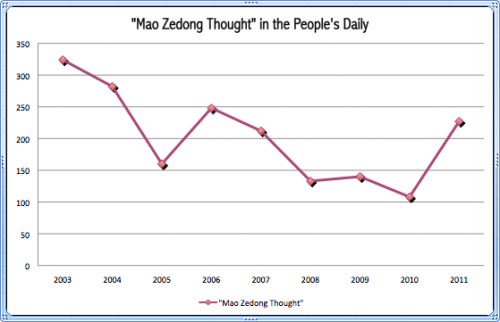

President Hu Jintao seems to have been even more tolerant of China’s Maoist left than his predecessor, Jiang Zemin, and has made no apparent attempts to stay the leftists’ advance. The following is a graph of occurrences of “Mao Zedong Thought” in the People’s Daily during Hu Jintao’s term in office:

The 2011 peak holds not just for the Party’s official newspaper, the People’s Daily, but also for its robust online portal, People’s Daily Online, where occurrences of Mao Zedong Thought in 2011 were higher than in the previous three years. This is a reflection of the din of so-called red propaganda, which was driven to a national climax in 2011 by the “red song” campaign of prominent Party “princeling” Bo Xilai, then a top Party leader in the city of Chongqing.

Since the dramatic fall of Bo Xilai in 2012, the term Mao Zedong Thought has cooled somewhat in China’s official Party media. In the first half of 2012, the term appeared 67 times in the People’s Daily (against 227 times for all of 2011). But there are no signs that the term is going away.

On July 12, 2012, China’s Central Party School held a commencement ceremony at which Xi Jinping, Hu Jintao’s presumed successor, delivered the address. According to the official news report from the People’s Daily, the graduates had, thanks to their activities at the school, “deepened their study and understanding of Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, and particularly the theory of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Not long after, on July 23, President Hu Jintao addressed a seminar of provincial-level Party cadres and spoke of the “guidance” of Marxism and Mao Zedong Thought.

Usage of the term Four Basic Principles by senior Party officials today is roughly the same as the term Mao Zedong Thought. Both are used sparingly, but are still in use. A search of the People’s Daily from the 17th National Congress in 2007 up to August 2012 shows that Hu Jintao, Wu Bangguo, He Guoqiang and Xi Jinping have all used the term Four Basic Principles. Premier Wen Jiabao has made many public speeches during this time, but not once since 2008 has he used Four Basic Principles or Mao Zedong Thought.

The Four Basic Principles (including Mao Zedong Thought) is an important measuring stick by which we can observe the political trends of the 18th National Congress. Before the 17th National Congress in 2007, many Chinese had hoped for the possibility of political reform. I wrote in an essay for Hong Kong’s Yazhou Zhoukan at the time: “Hu Jintao and his succession team have already come to the great door of political reform. The question of whether they can step over the threshold of history will be answered when we know whether their feet are still shackled by the Four Basic Principles.”

As it turned out, the Four Basic Principles and Mao Zedong Thought were both present in Hu Jintao’s political report, and in fact were used more frequently than in the political report five years earlier. On this basis, I concluded that “we cannot harbor romantic thoughts about the possibility of political reform in the next five years.” My conclusion has been borne out by political realities over the past few years. Now, once again, we can apply this measuring stick to see what possibilities the next five years might hold.