By QIAN GANG

Keywords: Cultural Revolution (文革 or 文化大革命)

Anyone who regularly observes the topsy-turvy world of Chinese politics understands that the past, even the remote past, can exert a powerful influence on the present and future. Major historical anniversaries — like that of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre or the founding of the Chinese Communist Party — can send either perennial chills or doctrinal fevers through China’s political culture and media. In China, the past is always present, even if, as in the case of Tiananmen, it cannot be readily talked about.

As we train our eyes on the 18th National Congress with a mind to reading China’s future, therefore, one of the most important signs to watch will be how China’s leaders deal with the country’s past. Specifically, how will the political report to the 18th National Congress deal with the Cultural Revolution, that period of political and social upheaval from 1966 to 1976 in which millions of Chinese were persecuted?

[ABOVE: Does the Cultural Revolution still loom behind contemporary Chinese politics? Wen Jiabao’s remarks at a press conference in March 2012 suggested tragedies like the Cultural Revolution could happen again in China if political reforms are not pursued.]

Several variants of the term “Cultural Revolution” are used in Chinese. The longest form, seldom used, is the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” or wuchan jieji wenhua dageming. More frequently used is the phrase “Cultural Revolution,” or wenhua dageming, and its shortened form, wenge. Originally, this term appeared quite regularly in the media, but in recent years it has become sensitive, and therefore rare.

In early 2012, as China edged closer to the 18th National Congress and leadership struggles came to a head in the ouster of Bo Xilai, an influential “princeling,” Politburo member and top leader of the municipality of Chongqing, more attention was paid to the Cultural Revolution in China’s media, and in society generally. Bo Xilai’s populist campaign of “red songs”, which some saw as a key part of his bid for a spot in China’s powerful Politburo Standing Committee, had seemed to invoke the Cultural Revolution — its aesthetic exterior if not its core principles. With Bo apparently swept from contention, the question was now open: how would Hu Jintao and his successors deal with the history of the Cultural Revolution and Mao’s leftist political line?

On March 14, 2012, before Bo Xilai’s fall was assured, and as the curtain closed on the National People’s Congress in Beijing, Premier Wen Jiabao held a press conference to answer reporters’ questions. This was Wen’s last press conference as premier, and he came prepared with some of his heaviest remarks yet on political reform.

A reporter from Singapore’s Straits Times asked, “In recent years you have raised the issue of political reform numerous times in various forums, and this has drawn a lot of attention. I’d like to ask why it is you continue to raise the issue of political reform. And where does the difficulty lie for China in carrying out political reforms?” Wen Jiabao responded as follows:

Yes, many times in recent years I’ve talked about political reform — already quite comprehensively and specifically, it should be said. As to why I’ve given so much attention to this, it is a matter of responsibility. After the breaking up of the ‘Gang of Four,’ our Party issued its [1981] Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the Republic and instituted economic reform and opening. But we have not yet fully rooted out the evil legacy of the errors of the Cultural Revolution and the influence of feudalism. Along with economic development, we have also had such problems as unfair distribution of income, a lack of credibility and corruption. I know only too well that resolving these issues means not just carrying out economic reforms, but also means carrying out political reforms, especially reforms to the system of Party and state leadership.

Right now our reforms have come to a key stage. Without successful political reforms, we cannot possibly carry out full economic reforms, the gains we have made so far in our reform and construction could possibly be lost, new problems emerging in society cannot be fundamentally resolved, and tragedies like the Cultural Revolution could potentially happen again. Every responsible Party member and leading cadre must have a sense of urgency about this.

We should, through reforms, gradually institutionalize and legalize socialist democracy in our country. This provides the basic guarantee that we can avoid a replay of the Cultural Revolution and realize long term peace and stability in our country.”

Responding to a separate question about the so-called “Wang Lijun Incident” of that February, in which the former top police official in the city of Chongqing — who had been spearheading Bo Xilai’s campaign against organized crime in the city — entered the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu apparently seeking protection, Wen Jiabao said sternly that the Party and government leadership of Chongqing “must engage in reflection.”

For Wen to talk about the Cultural Revolution, political reform and other sensitive issues at such a sensitive time drew great interest from media outside China. Ta Kung Pao, the Chinese Communist Party-aligned newspaper in Hong Kong, splashed a large, red headline across the top of its page-four special coverage of the NPC: “Failure of Political Reform Could Mean Repeat of Cultural Revolution.”

[ABOVE: Hong Kong’s Ta Kung Pao splashes Premier Wen Jiabao’s remarks about reform and the Cultural Revolution across page four.]

Even some mainland media dared prominent headlines. An article at QQ.com, one of China’s most popular internet news portals, read: “If Political Reforms Do Not Succeed, Cultural Revolution Tragedy Could Be Repeated.”

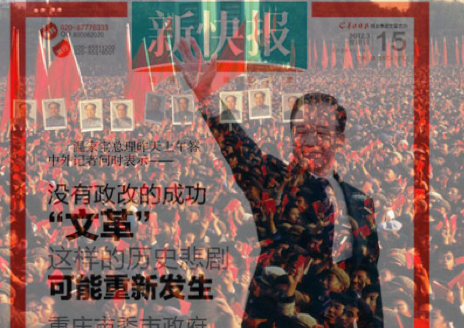

And the New Express, a leading commercial newspaper in the southern city of Guangzhou, ran a large picture of a waving Wen Jiabao on its front page. The headline to Wen’s left read: “Without Successful Political Reform the Historical Tragedy of the Cultural Revolution Could Be Replayed.” The phrase “Cultural Revolution” was bolded for emphasis in the headline.

[ABOVE: Wen Jiabao’s comments on the Cultural Revolution and reform make the front page of Guangzhou’s New Express.]

After 1976 in China, assessments of the Cultural Revolution were closely tied to political struggles within the Chinese Communist Party, struggles that of course determined what direction the country took.

The 11th National Congress in 1977 was the first major political meeting to be held following the death of Mao Zedong, the collapse of the Gang of Four, the end of the Cultural Revolution and the political comeback of Deng Xiaoping. Not only did this National Congress fail to deny the Cultural Revolution, it defined the fall of the Gang of Four as one of the great victories of the Cultural Revolution, and it continued to criticize former chairman Liu Shaoqi, who had been persecuted by Mao Zedong.

In fact, it took reformists in China, led by Deng Xiaoping, three full years to issue a full-fledged condemnation of the Cultural Revolution and its excesses. First, in the wake of the ouster of the Gang of Four, came the so-called “debates over the criteria for testing the truth,” a kind of mass movement of introspection arising from vehement objections to the words of then-Chairman Hua Guofeng, who remained supportive of Mao Zedong’s policies in spite of the havoc they had wrought, saying: “We will firmly uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made, following Chairman Mao’s instructions without hesitation.”

There was the rehabilitation of those involved in the 1976 Tiananmen Incident, in which thousands had mourned the death of former Communist Party leader Zhou Enlai in April 1976 (Zhou had passed away in January that year) against the wishes of top leaders like Jiang Qing and other members of the Gang of Four. There was the sentencing of the members of the Gang of Four, and of the clique of Marshal Lin Biao. Finally, there was a protracted discussion within the Party of the breathlessly named Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the Republic, which grappled with important questions lingering from the Cultural Revolution.

It was not until the end of 1981 that the Party issued a full condemnation of the Cultural Revolution. At the 12th National Congress in 1982, Hu Yaobang‘s political report criticized the Cultural Revolution. Five years later, Zhao Ziyang‘s political report to the 13th National Congress connected the issue of political reform to the prevention of further tragedies in China like the Cultural Revolution:

. . . [We must] through reforms ensure that socialist democracy gradually moves toward systemization and legalization. This is the most basic guarantee that we can prevent a replay of the Cultural Revolution and achieve long-term peace and stability.

In the 1980s it was essentially not sensitive to talk about the Cultural Revolution, although a small number of creative works and theoretical writings were suppressed because they directly criticized China’s political system. In fact, discussion of the Cultural Revolution was beneficial to Deng Xiaoping as he sought to consolidate his power and push ahead with his reform agenda.

After the June Fourth Incident in 1989, there were far fewer references to the Cultural Revolution in the speeches of Party leaders. In his political reports to the 14th and 15th National Congresses, when President Jiang Zemin praised Deng Xiaoping’s legacy and placed it in its historical context, he made passing mention of the Cultural Revolution. In his report to the 16th National Congress in 2002, Jiang Zemin made no mention at all of the Cultural Revolution.

Since coming to office, President Hu Jintao has mentioned the errors of the Cultural Revolution on at least five occasions. One was the commemoration in 2003 of the 110-year anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth. Next came the 50-year anniversary in 2004 of the founding of the National People’s Congress. That was followed by a speech to a special topic discussion among provincial leaders in 2005, a speech celebrating the 110-year anniversary in 2008 of the birth of Liu Shaoqi, and, finally, his speech to commemorate the 30th anniversary of economic reforms in 2008. In his report to the 17th National Congress in 2007, Hu Jintao mentioned the Cultural Revolution in explaining — as Jiang Zemin had — the historical context of Deng Xiaoping’s achievements. But in none of his speeches has Hu Jintao summarized and reviewed the lessons of the Cultural Revolution.

The sense in China’s media over the past few years has been that the space for discussion of the Cultural Revolution is actually diminishing further. When the 40th anniversary of the onset of the Cultural Revolution rolled around in 2006, many Chinese media had planned to do retrospective reports, but these were stopped across the board by a ban issued from the Party’s Central Propaganda Department.

There is a close match between the determination to forget the Cultural Revolution and the present stagnation of political reform in China. The Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao eras have spanned the 70th, 80th and 90th anniversaries of the founding of Chinese Communist Party, crucial milestones for the Party leadership.

In his speech to commemorate the 70th anniversary in 1991, Jiang Zemin did mention that “for a period of time, under the influence of the left, a number of mistakes were made, particularly such serious setbacks as the Cultural Revolution.” Ten years later, commemorating the Party’s 80th anniversary, Jiang Zemin made no mention at all of the Cultural Revolution. President Hu Jintao similarly absented the Cultural Revolution in his 2011 speech to commemorate the 90th anniversary.

Since 2009, in fact, Hu Jintao has made no mention of the Cultural Revolution in any of his publicly available speeches. It was in that year that Chongqing’s charismatic top leader, Bo Xilai, launched his nationally popular campaign against organized crime in the city, along with his mass mobilization movement of “red” culture promotion and its Cultural Revolution-style nostalgia. Events in Chongqing emboldened China’s Maoist left, which has been more active and influential since 2009.

Progress on the issue of political reform in China has already become inseparable from reckoning with the Cultural Revolution. That decade touches directly on what is now most central to China’s development: creating checks and balances as restraints on political power. At its most basic, the question is this: does China move forward to establish a system of constitutional governance, or does it slide backward into a new era of Mao-style political movements, fanning populism, breaking and remolding society, wiping away competing ideas?

It was against this backdrop that Wen Jiabao’s remarks about political reform and the Cultural Revolution created such a stir in China in 2012. In a sense, Wen was breaking through a taboo about discussion of this historical tragedy that has prevailed in recent years. He was using the opportunity presented by dramatic events in Chongqing to raise again the point Zhao Ziyang made in his political report to the 13th National Congress in 1987, that political reform was necessary to prevent a replay of the Cultural Revolution.

One issue to watch at the 18th National Congress is whether and how China’s past will be dealt with in the political report. Will the phrase “Cultural Revolution” make a more prominent showing? How will it be talked about?