By QIAN GANG

Keyword: socialism with Chinese characteristics (中国特色社会主)

In China, there is a popular phrase people use when referring to the seemingly whimsical world of the political slogan: “It’s an open basket,” they’ll say of this or that watchword, “Anything can be thrown in there.” This could be said of just about all the specialized vocabularies I have covered in this series. And it is certainly true of one of the most central phrases now in use by the Chinese Communist Party — “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” or zhongguo tese shehui zhuyi.

As we prepare for the 18th National Congress, this term in fact is celebrating its 30th birthday, and it is running as strong as ever. There is little doubt this watchword will appear, probably prominently, in the next political report. The real question is exactly what Chinese leaders will use to fill this basket.

The patent rights, so to speak, on socialism with Chinese characteristics go back to Deng Xiaoping. Deng first used the term in his opening remarks to the 12th National Congress in 1982, which were printed in the People’s Daily. For Deng, this was a reform slogan, and the obvious target of his reform was the Mao-style socialism that had been practiced to great detriment in China for 30 years.

By the time the congress rolled around in 1982, the Party had already dissolved the people’s commune system in China’s countryside, and market reforms had begun. In fact, Deng’s true intention was to practice not socialism with Chinese characteristics, but capitalism with Chinese characteristics. But the changes he initiated were already drawing opposition from conservatives in the Party ranks. Deng had to proceed cautiously. He could not force a break with the political orthodoxy without losing important allies needed to push reforms.

Deng’s introduction of the term “socialism with Chinese characteristics” was a stratagem, what my Western readers might call a Trojan horse. Better yet, to return to the popular Chinese phrase, it was a basket. On the outside, it seemed ideologically acceptable to conservatives, but inside it could accommodate Deng’s vision of change. The crux of the term is not “socialism” but “Chinese characteristics.” The modifier “Chinese characteristics” enabled Deng to qualify and adapt socialism, easing it in a new direction. This was Deng’s great magic trick, you might say — making people believe socialism was still there even though it had disappeared right before their eyes.

In 1982, socialism with Chinese characteristics was a newborn watchword. It had not yet appeared in General Secretary Hu Yaobang’s political report to the 12th National Congress, held in September that year. The term rose to prominence only after Deng Xiaoping, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang laid out their blueprint for further reform.

The following are the full titles of the political reports delivered to national congresses in China, from the 12th in 1982 to the 17th in 2007. For anyone unaccustomed to the Party’s windbag ways, these will no doubt seem a marvel of expansiveness:

12th: “Fully Creating a New Phase in the Socialist Construction of Modernization” (Hu Yaobang)

13th: “Moving Forward Along the Path of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” (Zhao Ziyang)

14th: “Accelerating the Pace of Reform and Opening and the Construction of Modernization, Striving for Greater Victories in the Enterprise of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” (Jiang Zemin)

15th: “Holding High the Glorious Banner of Deng Xiaoping Theory, Pushing the Building of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics into the 21st Century” (Jiang Zemin)

16th: “Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in all Respects, Opening a New Phase of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” (Jiang Zemin)

17th: “Holding High the Great Banner of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, Struggling for New Victories in the All-Round Building of a Moderately Prosperous Society” (Hu Jintao)

[ABOVE: In 1987, the front page of the People’s Daily reads: “Moving Forward Along the Path of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.”]

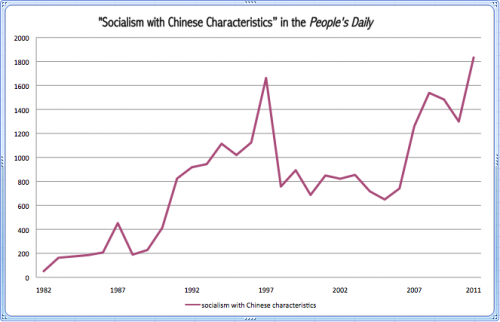

My point here is that every single political report since the 13th National Congress in 1987 has included socialism with Chinese characteristics in the title. This, indeed, is the 400-pound gorilla of Party watchwords. Both the reports to the 13th and 14th congresses referred to socialism with Chinese characteristics as a “banner.” The report to the 15th National Congress, held in 1997, the year of Deng Xiaoping’s death, mentions the “Glorious Banner of Deng Xiaoping Theory,” which essentially has the same meaning as the previous two references to socialism with Chinese characteristics. From the 15th National Congress to the 17th National Congress, the reference to the “Glorious Banner of Deng Xiaoping Theory” was prevalent and socialism with Chinese characteristics faded somewhat. In Hu Jintao’s report to the 17th National Congress in 2007, however, the reference to socialism with Chinese characteristics as a “banner” returned, marking a general resurgence of the term.

So, what exactly is socialism with Chinese characteristics? Can anyone really say?

Every political report since the 13th National Congress in 1987 has been accompanied by an elaborate treatment. These explanatory notes serve as a kind of political bible for ordinary Chinese — a tuning fork that gets everyone on the same note. If we look carefully at these treatments, we can spot how watchwords shift in meaning.

The 13th National Congress was marked by a fierce struggle between the reform faction and the leftist conservatives. At that time the explanation of socialism with Chinese characteristics, which was called the “basic line,” was explained like this: “[The term means] leading and uniting people of all ethnic groups, with economic construction as the core, adhering to the Four Basic Principles, adhering to reform and opening, with self-reliance, [with a] tough and pioneering [spirit], struggling to transform our country into a strong and prosperous, democratic and civilized modern socialist nation.” Within this explanation, “reform and opening” and the Four Basic Principles are afforded equal position. In the context of the 1980s this actually gave reform and opening the upper hand.

The 14th National Congress was held three years after the June Fourth Incident at Tiananmen Square that marked the violent end to pro-democracy protests in 1989. Even as he faced off with a resurgent left — which was making political hay of the unrest in 1989 — Deng was adamant that not a single word of the 1987 political report be altered. In the spring of 1992, before the congress was held, Deng broke the stalemate by making his “southern tour,” a whistle-stop tour of economically important cities in the south during which he promoted an acceleration of reforms.

In his political report later that year, Jiang Zemin stressed that while the Party’s leaders had to be mindful of a rightward shift they had to remain especially vigilant against threats from the left. Deng’s southern tour had succeeded in tipping the scales in favor of reform.

By the 15th National Congress in 1997 the market economy was already well established and China was preparing for entry into the World Trade Organization. Once again, Jiang Zemin warned the Party to stay the course and not shift to the left. He said the country and the Party needed to be “even clearer about what is meant by the primary stage of socialism, [and by] a socialist economy, politics and culture with Chinese characteristics.”

Jiang was once again transforming socialism with Chinese characteristics, filling the basket with several changes to ownership systems in China. Now the term also implied the creation of a basic economic system in which various new forms of ownership could operate. In practice, this was already a far cry from the call to stick to the “socialist path,” an integral part of the Four Basic Principles (another watchword I addressed here).

Five years later, Jiang Zemin no longer cautioned leaders to be alert to a leftward shift. In his political report to the 16th National Congress, he summarized the Party’s achievements in the “construction of socialism with Chinese characteristics,” breaking them down into 10 points. These included Mao Zedong Thought and the Four Basic Principles (both much beloved by those on the left). Most crucial, however, was Jiang’s closing statement. Wrapping up his 10 points, he said the Party must “represent the developmental needs of China’s advanced production capacity, represent the forward direction of China’s advanced culture, and represent the fundamental interests of the majority of the people.”

This, of course, was the so-called Three Represents, Jiang’s banner term, or qihao — an issue I dealt with in my last piece. Jiang Zemin was now stuffing the basket of socialism with Chinese characteristics with his own political term, a symbol of his legacy.

Not surprisingly, Hu Jintao’s political report to the 17th National Congress in 2007 made further revisions to socialism with Chinese characteristics. Hu’s words were (and I’ll have to plead with readers to bear with me):

. . . The road of socialism with Chinese characteristics is about building a socialist market economy, socialist politics, a socialist advanced civilization and a socialist harmonious society, building a modern socialist nation that is prosperous, democratic and civilized, [all] under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, rooted in the basic circumstances of the country, with economic construction as the core, adhering to the Four Basic Principles, adhering to reform and opening, liberating and developing the productive forces of society, consolidating and improving the socialist system. . . The theoretical system of socialism with Chinese characteristics is a scientific theoretical system that includes Deng Xiaoping Theory, the important ideologies of the Three Represents and the Scientific View of Development and other important strategic ideas.

And there you have it, not a lucid definition of socialism with Chinese characteristics, but a perplexing mixed bag of Party watchwords. The phrase “other important strategic ideas” reminds us that this is a collection of evolving ideologies. You could see it as the accumulating sum of China’s political baggage.

Hu Jintao essentially repeated this definition, such as it is, in his speech to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2011. In a speech on July 23, 2012, Hu added that “socialism with Chinese characteristics is a banner for China’s present-day development and progress, and a banner of unity and struggle for the whole Party and all the peoples of the nation.” This was tantamount to saying that the term will also, in the future, remain a banner standing for all three of the latest leadership generations — Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

[ABOVE: The July 24, 2012, edition of the People’s Daily touts socialism with Chinese characteristics as a basket of banner terms.]

The front page of the July 24, 2012, edition of the People’s Daily, shown above, offers a hint about the upcoming 18th National Congress. In the upper right-hand corner of the page, the three banner terms of Deng, Jiang and Hu are listed out. The main headline, meanwhile, emphasizes socialism with Chinese characteristics. From this we could hypothesize that no entirely new watchwords will be unveiled at the congress. Rather, socialism with Chinese characteristics will be contested among various political interests and factions, emerging once again as the greatest common denominator.

What we will need to watch is how socialism with Chinese characteristics is explained. How will it be different? Will it continue to bear the ideas of Jiang Zemin, or the Four Basic Principles, or Mao Zedong Thought? Inside the evolving basket of socialism with Chinese characteristics, will Hu Jintao’s Scientific View of Development have a new and special place? Will the Scientific View of Development become, like the banner terms of Deng and Jiang, an idea merely offering “guidance,” or will it be once again defined (as it has been more recently) as a fundamental policy to be loudly proclaimed, and followed reverentially, by China’s next leader?