Understanding that all eyes are now turned to the annual “two meetings” (两会) of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), we turn to different story — the 10-year anniversary of the SARS epidemic.

It was in March 2003 that the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, or SARS, became international news. Hong Kong announced on March 11 that it was in the midst of a crisis. A few days later the World Health Organization confirmed cases in other countries. China, meanwhile, kept a lid on information about the outbreak within its own borders.

Bowing to international and domestic pressure, China finally changed course on SARS in late April. Beijing mayor Meng Xuenong was sacked on April 21, and the dismissal of China’s health minister, Zhang Wenkang, came soon after.

Through May and June 2003 there was a sense (and a hope) that China’s leadership was heading in a new direction, toward greater openness and transparency. There was even talk of a “media spring” in China as a new generation of commercial media hit hard on SARS and other stories, like the beating death of young migrant Sun Zhigang.

Those hoping for bigger and bolder political change in the wake of the SARS epidemic were setting themselves up for disappointment. Once the crisis had passed, Party leaders reasserted control. Media that had been bolder in their reporting of SARS and other stories were disciplined that summer.

But how did SARS change China? Has progress been made on issues like crisis preparedness?

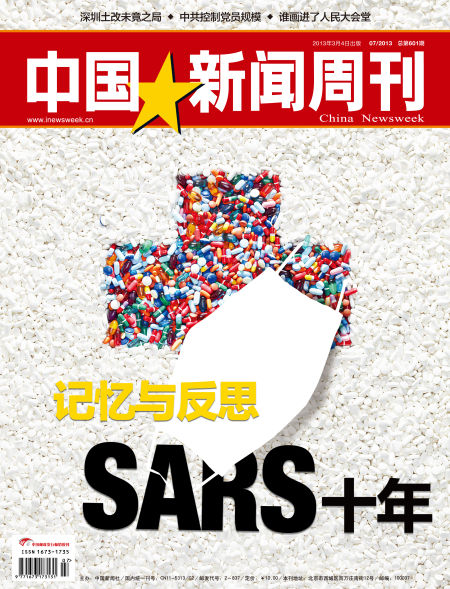

In recent weeks a number of Chinese media have used the occasion of the SARS anniversary to take a broader look at China since SARS. The epidemic and its impact took the cover of the last edition of China Newsweekly magazine.

[ABOVE: The cover of the February 28 edition of China Newsweekly magazine: “Remembering and Reflecting Back on SARS Ten Years On.”]

Unfortunately, we can’t tackle translation of the entire report, but here is a taste, starting with the section about changes to China’s public health infrastructure:

Putting Public Health on the Fast Track

Once we “bid farewell” to SARS . . . it put China on the fast track to public health development. Zeng Guang (曾光) and other public health experts interviewed [for this story] all said that in the 10 years since SARS spending on public health in various areas has gone up by multiples of 10 or in some cases 100.

“SARS was a disaster,” says Hu Yonghua (胡永华), a professor in the School of Public Health at Peking University. “But it was also an opportunity, an opportunity for development of public health in China.”

Before SARS, the entire public health system, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, were in a state of transition — from fully subsidized state-run institutions to partially state-run institutions. This meant that they no longer served merely a public health role, but had to go out an make money for themselves as well.

Given this environment, says Hu Yonghua, public health organisations devoted most of their energy to survival through profit-making endeavours. “Before, the strongest [providers] were focused on operation [in various health services], but now the strongest were focused on income-generation. As funds were in short supply, many areas of operation fell by the wayside, existing only in name,” he said.

“SARS was like a mirror, reflecting all at once many public health problems that for a long time had been ignored,” said Hu Honghua.

Zeng Guang told China Newsweekly that after SARS the entire public health system entered a capacity building phase such as had never before been seen. The government spent 11.7 billion yuan to address deficiencies in hardware for the disease control and prevention system at the national and provincial levels. One classic example of hardware upgrades came in the building of negative pressure isolation wards.

Now these wards built especially to receive contagious patients suffering from respiratory issues are not only a common feature in [Chinese] hospitals, but a number of cities are now equipped with pressure isolation ambulances. These allow maximum prevention of infection when patients are being transferred [to healthcare facilities]. But 10 years ago when SARS struck hardly a single up-to-standard negative pressure isolation ward could be found in all of China!

In Zeng Guang’s view the most effective hardware upgrade was the building of an information and reporting system. Here is how he described the information and reporting system in the 1990s to China Newsweekly: “At that time, a national conference on epidemic disease was held just once a year. It was tallying of accounts (算账会) in which each representative from various provinces would bring their own tally. It was very backward.”

In fact, before the outbreak of SARS, China’s information and reporting system for public health was in effect non-existent. At that time [of SARS], the acting minister of health, Gao Qiang (高强), [who had taken over from sacked health minister Zhang Wenkang], had to check with each and every one of Beijing’s 175 [level-one] and [level-two] hospitals to arrive at numbers for [SARS] cases in the Beijing area, and this took a full week.

In the years following SARS, the Ministry of Health took the lead in building a public health monitoring and warning system (公共卫生监测预警系统), creating a comprehensive and strict information reporting system. Drawing particular attention was an epidemic network reporting system (疫情网络直报系统). Talking about this system, Zeng Guang calls uses two superlatives, calling it “definitely the world’s fastest, and definitely [the world’s] most advanced.”

. . .

The Bonus Benefits of SARS

When talking to China Newsweekly about the impact of SARS on public health in China, public health experts across the board also talked about the creation of emergency response plans (应急预案).

Among the many reasons behind the early failure to deal with SARS, says Zeng Guang, the first was that no plan existed for responding to a sudden-breaking public health incident.

Before SARS, China had no emergency response plan, no threat-level standard for sudden-breaking public health incidents, and no chain of command [for response] in the event of a public health crisis. It also had no system of responsibilities in place [outlining the responsibilities of various officials in the event of a crisis]. Moreover, there were no stipulations whatsoever about how information should be released, how to deal with news media, how various government offices should coordinate, how society should be mobilised or what major control measures should be taken in the event of a public health crisis.

So in the early stages of SARS, the response was chaos. Only on April 21 [when the health minister was sacked], did the Ministry of Health create a system for daily release of information about the epidemic. It was only two days later, on April 23, that the State Council created its SARS Prevention Command Center (防治SARS指挥部) to coordinate SARS prevention and response nationwide. It was only after this that the work of battling SARS got on the right track.

Visiting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 1, 2003, vice-minister Wu Yi (吴仪) said that one of the major goals of her visit was to promote the building of a comprehensive system for [dealing with] sudden-breaking health crises in China. This was the first time a Chinese leader publicly addressed the issue of an emergency response system.

On May 9, 2003, the State Council released its “Ordinance on Response to Sudden-Breaking Public Health Incidents” (公共卫生突发事件应急条例). This regulations, which was seen as a “turning point in public health,” had taken only two weeks from drafting to final approval. . .

The year after the Ordinance took effect, the Ministry of Health created its Health Emergency Response Office (卫生应急办公室), responsible for monitoring and warning on sudden-breaking public health incidents, as well as response preparedness and other work. By [the end of] 2005, 24 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities had created health emergency response offices.