In December 2011, a large-scale revolt in Wukan to protest a land grab by local officials catapulted this small, seaside village into world headlines. A rare negotiated settlement with provincial officials allowed Wukan villagers to hold democratic elections for a new village leadership on March 3, 2012 — what many called a new model for democracy in China.

This month I went to the village to see for myself how the “Wukan model” had progressed in the year since village elections. What I found was frustration, disappointment and exhaustion.

[ABOVE: A Wukan villager, still waiting for resolution of the land issues that sparked protest in late 2011. Photo by Anna-Karin Lampou.]

Villagers everywhere on Wukan’s streets echo the same refrain: “Still, our land has not been returned,” they say.

Land issues top the village committee’s agenda today as they did during elections last year. But committee members say their hands are tied by political forces beyond the village. While they represent the villagers who elected them, they must rely on Party superiors up the line to accomplish many of the things they originally set out to do.

Inside the village, division rankles. In October 2012, Zhuang Liehong, one of the elected committee members who had pledged most vocally to win back the village’s land, resigned his post, citing irreconcilable differences with Secretary Lin Zuluan and other committee members.

“It wasn’t personal,” Zhuang tells me over cups of oolong in the village teahouse he opened after his resignation. “We think differently. Right now it’s just impossible [for us to work together].”

In stark contrast to the unity Wukan showed the world in the midst of the protests, villagers now find it impossible to reach agreement even on how to use existing land. And evidence of the stalemate is everywhere.

[ABOVE: “Fully (Asia) Development,” a local knitwear factory, now sits idle outside Wukan. Photo by Anna-Karin Lampou.]

Surrounding the village, large stretches of land sit unused. Deserted factories, with smashed-out windows and rusty door frames, dot the village landscape. Posted outside an abandoned knitwear factory — “Fully (Asia) Development,” reads the sign at the gate — one security guard tells me he’s been keeping watch here ever since the factory’s boss absconded, after the village committee had demanded outstanding rent.

“He had a Hong Kong ID card,” the guard explains. “So they were never able to find him.”

Land disputes like Wukan’s have played out again and again in villages across China. According to a recent study, four million people each year in China have their rural land seized by the government. These land seizures drive an undercurrent of unrest. Sun Liping, a scholar from Tsinghua University, estimates that there were at least 180,000 land-related protests in China in 2012 alone.

For many, Wukan offered a solution — a model of democratic reform that could stem the tide of mass rural protests. Inside Wukan, that hope is at best a distant thought, crowded out by the immediacy of concerns over land.

When I spoke to one woman at a noodle shop about how things were going in Wukan, she talked at great length about how the village’s land still hadn’t been returned. When I asked her for her thoughts on democracy, she shrugged off the question: “I don’t really know about that,” she said.

I know the headlines have been down on Wukan in recent months. “Freedom fizzles out in China’s rebel town of Wukan,” read a recent Reuters report. “Is Wukan a failure?” a recent online post asked.

I’m not ready to say that democracy has failed in Wukan. There is positive progress, albeit small, towards a more open, transparent style of government. Locals told me they were happy they could now approach their local leaders, that they could voice their concerns and be taken seriously.

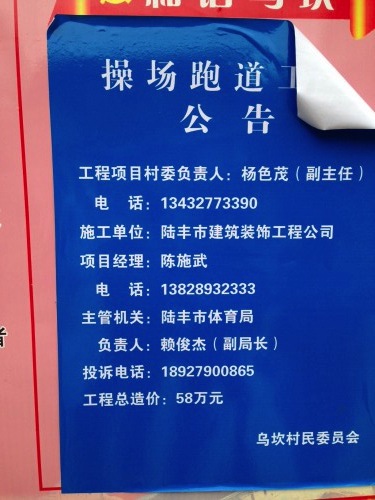

[ABOVE: A notice on the wall of a local school informs villagers about a renovation project, providing details such as the name of the contracted company. Photo by Anna-Karin Lampou.]

On the wall of a local kindergarten in Wukan, I came across a notice announcing a renovation project. It listed the name of the committee representative responsible for the project, including his phone number. It mentioned the company contracted to handle the renovation and the budget involved. That may seem like a small achievement. But this level of transparency is unusual in China, whether at the local level or the national level.

Behind the scenes, though, Wukan’s fragile experiment is exhausted. Yang Semao, the village committee member listed on the poster as being responsible for the renovation project, told me he is taking leave from the committee to deal with his failing health. The responsibilities and frustrations of the past year have left him physically and emotionally drained. He described himself as “near collapse.”

[ABOVE: Elected village committee member Yang Semao says he is exhausted by work and will be taking a period of leave from his responsibilities. Photo by Anna-Karin Lampou.]

A hand-written letter Yang shared with me, detailing the recent situation in Wukan and his reasons for taking leave, is a portrait of a village at an impasse. The frustration and fatigue are salient. But there is a thread of hope too. The village is trying to nurture its fledgling democracy, Yang says, educating its members about how to “express their demands rationally,” and preparing for elections down the road.

As for the insoluble issue of land — that may take several administrations to solve.

“The task is heavy,” Yang writes, “and the road is long.”

My Thoughts One Year On From My Election as Deputy Chairman of the Village Committee

Greetings to you all, respected [members of the] Provincial Work Group, Party and government leaders at various levels, departmental staff, friends in the overseas media, netizens who have watched [events in] Wukan, volunteers, and villagers of Wukan.

I thank you for your trust and support, which made possible my election as deputy chairman of the Wukan village committee, and which gave me the opportunity to serve the villagers of Wukan. However, as the weight of history and the expectations of villagers have been so considerable, and as my own experience has been inadequate, a great number of defects have emerged in my own work over the past six months. Progress on land-related appeals [made by the villagers of Wukan] has been laborious; negotiations over the [settling of] the boundary lands (四至边界); the procedures for livelihood projects (such as running water) have lacked consistency; village rules and regulations have not been readily followed (on illegal construction, for example); the pace of management of village affairs has been excruciating, and the course of democracy [in the village] now faces a serious predicament. The village bristles daily with criticism, and is has become difficult to establish the authority of the village committee. Facing the expectations of the government, of the villagers and of people of all walks of [Chinese] society, I feel a deep sense of shame.

Without question, my work has not been done well, but this is not out of lack of effort. In the year since I was elected (plus the six months of rights defense efforts) I have made a tremendous effort to address the demands and promote the development of my hometown. I have relented a single day, nor perhaps have I rested a single day. A few days ago the Bureau of Land Resources announced that our demands concerning our [village] land were at an impasse. The decision on the 124 mu of land [in question] has been delayed over and over again, and there are still obstacles to the restoration of the land title to the village of Wukan. Whenever this issue is broached, attacks come [from the authorities]. As for myself, I am perhaps psychologically near collapse. My constitution is now weak (I’m sick). In order that I do not perish of exhaustion and ill health, I have had no choice but to submit a request to the village committee for sick leave, allowing me some time to recover. If I recuperate for two weeks, I should be able to return to work. If the results are not as ideal as I expect, it might be necessary for me to take more time, or to resign my post in order to regain my health. I hope that in this I may have the support and understanding of the government and the people.

After I go on leave, many village affairs, including the land-related demands and livelihood projects, will depend upon the “two committees” (两委) — [the village branch of the Chinese Communist Party and the autonomous villagers’ committee] — the village affairs supervisory committee and the other various village work groups. I hope that all of you together support the work of Secretary Lin [Zuluan], that you unite around Secretary Lin, that you manage village affairs well, and that you do a good job of various livelihood projects and in promoting land-related demands — that you dedicate yourselves to the stability and development of Wukan Village. I will be back to join with you [in this work] as soon as I can.

On the question of land issues in Wukan Village . . . The task is heavy and the road is long. Owing to historical problems and other complexities, this issue is one that cannot be resolved in a single term by this village committee. It is an issue that will require several terms to achieve (and that of course also requires a capable village committee).

The current village committee has now begun to shift the center of its work to directing villagers toward a more rational expression of their demands and consolidating the democratic achievements we have made. [Our focus is on] progressively and gradually developing democracy and bringing stability to the social environment in Wukan, creating a favorable election environment for the next village committee term. As for the resolution of [outstanding] land issues, and promoting productivity and investment, these [tasks] can only await breakthroughs to be made by the next village committee.

Yang Semao (杨色茂)

March 3, 2013

(Translation by David Bandurski)