Peng Shuai plays at the 2010 US Open. Image by Robbie Mendelson available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

The case of Chinese tennis champion Peng Shuai (彭帅) entered a bizarre new phase last week as the overseas accounts of Chinese state-media and associated media personalities made an apparently concerted effort to allay growing concerns internationally about the athlete’s wellbeing. But the extreme nature of the restraints on speech about Peng, and the appropriation of her voice by the organs of external propaganda, should be sufficient proof that she is now subject to serious restraints on her personal freedom.

“The Thing People Talked About”

On November 18, more than two weeks after Peng’s November 2 post accusing former vice-premier Zhang Gaoli (张高丽) of sexual assault, CGTN, the international arm of the state-run China Media Group, posted a letter to Twitter that Peng Shuai had reportedly sent to Steve Simon, the chairman of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). In the letter, Peng seemed to claim that she was “not missing, nor am I unsafe.” “I’ve just been resting at home and everything is fine,” the letter said.

Far from easing growing concerns over the tennis star’s wellbeing, the letter ratcheted up suspicions.

The next day, as the CGTN letter became the focus of international speculation, the WTA having rejected it as credible proof that Peng was safe, Global Times editor-in-chief Hu Xijin apparently sought to quell concerns by writing on Twitter that foreign media were engaging in senseless speculation. Hu seemed unable even to speak frankly about the case, however: “As a person who is familiar with Chinese system,” he wrote, “I don’t believe Peng Shuai has received retaliation and repression speculated by foreign media for the thing people talked about.”

The same day, Shen Shiwei (沈诗伟), a Paris-based reporter for Hu Xijin’s newspaper, shared photos on Twitter that she claimed were from Peng Shuai’s WeChat account. They showed Peng apparently playing happily with her pet cat, surrounded by a collection of plush toys. Replying to Shen’s Twitter post, Hu Xijin said he was “willing to believe the authenticity of these photos.”

Hu Xijin’s next attempt to leverage his overseas following on Twitter came late in the day on November 20, as he posted a pair of videos he had obtained from unidentified sources. “I acquired two video clips, which show Peng Shuai was having dinner with her coach and friends in a restaurant. The video content clearly shows they are shot on Saturday Beijing time,” Hu wrote.

On Sunday, November 21, Hu posted a video of Peng attending the finals of a youth tennis competition and waving to unseen spectators. “Global Times photo reporter Cui Meng captured her at scene,” Hu wrote.

Hu attempted to turn the tables on the Western media who refused to accept at face value attempts to offer evidence of Peng Shuai’s wellbeing that seemed clearly staged. “Can any girl fake such [a] sunny smile under pressure?” he asked. “Those who suspect Peng Shuai is under duress, how dark they must be inside. There must be many forced political performances in their countries.”

Leaving aside the ugly fact that here is a privileged male within a closed media system dominated by the ruling political party speaking diminishingly of a professional woman, age 35, as a “girl,” how could Hu’s denials and counterattacks possibly convince journalists, politicians and audiences globally? After all, Peng Shuai had not yet spoken. She had nodded at a dinner table, in a carefully edited video in which another male had spoken, ludicrously, about what day it was. She had turned, masked, in another video from which the audio had been entirely removed (the camera lingering on a date posted on the door). The overriding fact here was that Peng’s voice could not be heard. She was unreachable, even though the letter to the WTA shared through the overseas social accounts of state media had quoted her as asking the organization to verify any future news with her first, and “release it with my consent.”

In the latest gambit to prove that everything is fine, and that the world can simply move on when it comes to Peng Shuai and her allegations on November 2, the International Olympic Committee revealed Monday that its president had spoken to Peng Shuai by video on Sunday and confirmed that the tennis star is “safe.” The IOC announcement prompted further skepticism outside China, the organization accused by some as having involved itself in a “publicity stunt.”

External Propaganda, Internal Darkness

The most damning fact in the Peng Shuai case is that all information about the tennis star, her allegations and her personal wellbeing has been completely expunged from media and the internet. The comments made by Hu Xijin and others associated with Chinese state media may seem like the advance front of a global narrative to counter the concerns of the world – Peng is fine, there is nothing to see (我很安全) – but there is in fact no core narrative at all, no real and convincing alternative explanation for what has unfolded this month.

Even the letter, the images and videos that Hu and CGTN have deployed in an attempt to convince the world do not exist in the alternate universe of Chinese information. They have been scrubbed from the internet. They have not been shared or referenced at all in mainstream media coverage.

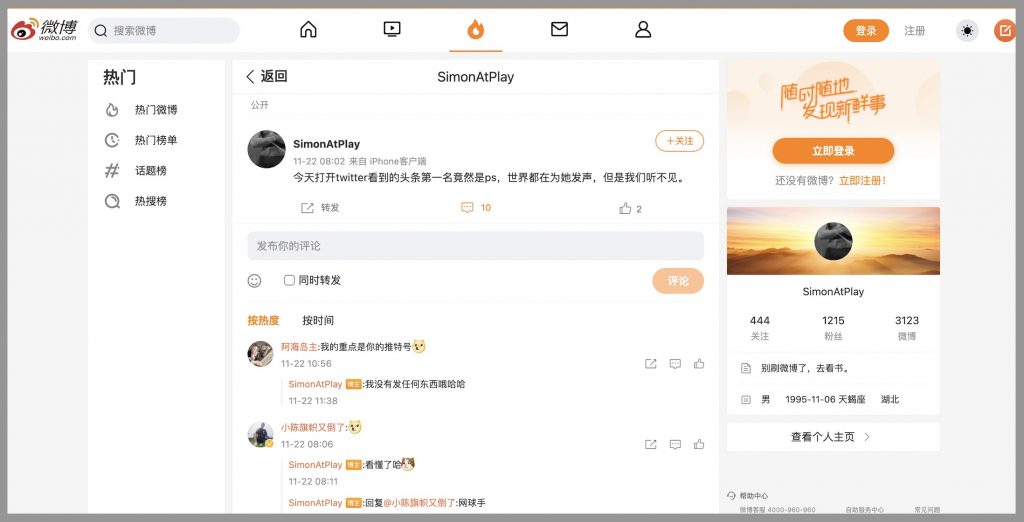

One Weibo user said it well yesterday when they posted a message referring to Peng Shuai only as “PS,” because her name has become a blocked keyword: “Opening up Twitter today, I see that the first name in the headlines is [Peng Shuai]. The world is speaking for her, but we can’t even hear it.”

Surely, Hu Xijin must have posted something to Weibo, where he has more than 24 million fans? Since November 18, Hu has posted about US-China relations and the recent Biden-Xi video meet. He has posted about alleged bias in the Western media, focusing on a report by Reuters about a Chinese professor at a European university working with a Chinese military laboratory, which on Twitter was accompanied by an image of Chinese soldiers (prompting an apology from the news agency). He has written about Lithuania “undermining China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and violently interfering in China’s internal affairs.”

But there is nothing, not a word about Peng Shuai.

A search in the Baidu search engine for “Hu Xijin” and “Peng Shuai,” selecting for web pages from the past week only, turns up just two pages. But these are not from the past week, nor do they have anything to do with Peng Shuai’s wellbeing. The first is a link to People.com.cn, the official website of the Chinese Communist Party’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper – not to any particular page, but rather to an archived homepage from January 2014.

The top headline on this archived homepage is for a featured profile, appearing at the time in the provincial-level Henan Daily, of Xi Jinping as a county-level leader in the 1980s.

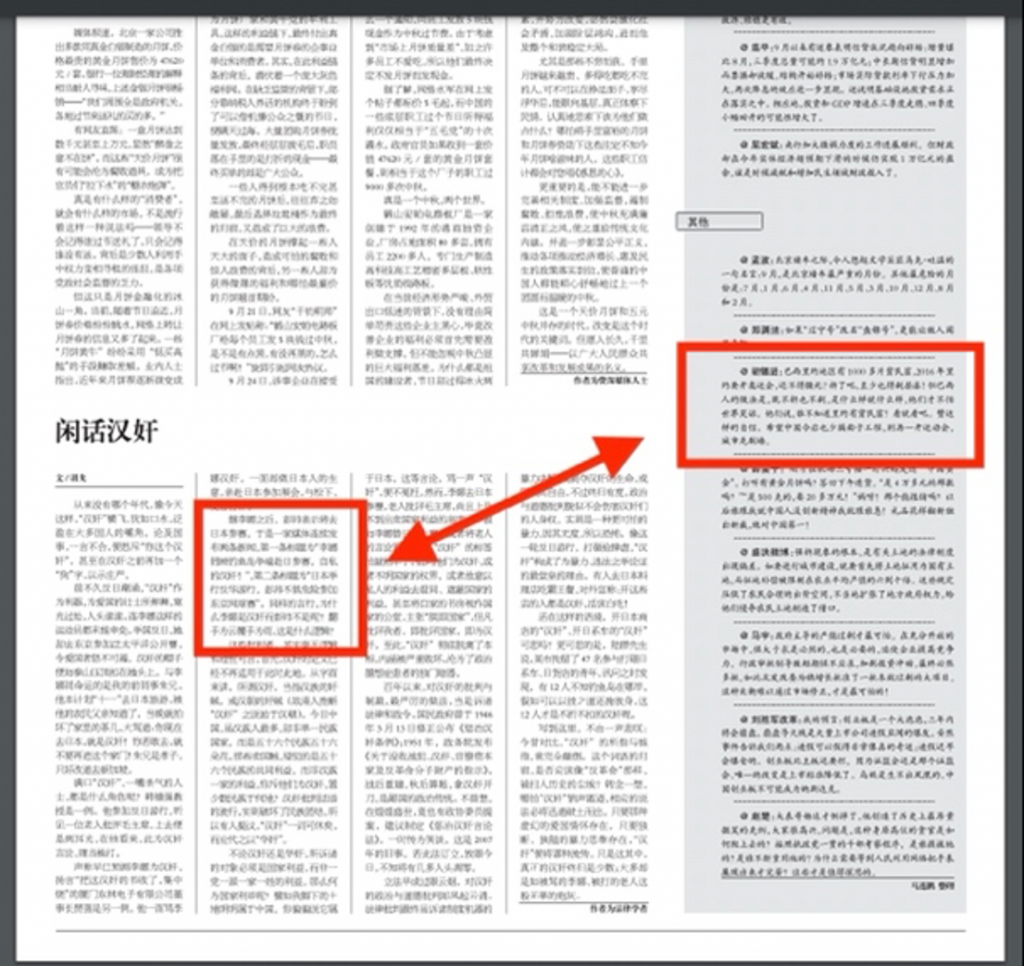

The second search result generated through Baidu is an instance in which both “Hu Xijin” and “Peng Shuai” appear. But it is not recent news, and has nothing whatsoever to do with Peng’s recent whereabouts, or Hu Xijin’s remarks on the issue. Instead, it is a single inside page of the October 1, 2012, edition of the China Business Journal, a newspaper published under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

The bottom half of the page is occupied by an article called, “Idle Talk of Traitors” (休话汉奸), that discusses, with a slightly admonishing tone, the flippant use by online nationalists of the label “traitor” against Chinese participating in various international events. They included Li Na (李娜), who in 2011 won the French Open, becoming the first Asian-born tennis player to win a Grand Slam singles title. Li Na was being branded a traitor online for taking part in a tournament in Japan in the midst of disputes over the Senkaku Islands. But Peng Shuai was spared similar treatment at the time. “Making the same remarks, how is it that Li Na is a traitor and Peng Shuai is not?” the article asked. “What logic is this?”

The superficial link with Hu Xijin comes as a “Sina Weibo” column on the right-hand side of the page highlights a number of recent Weibo posts that have drawn attention online. One of these is a post from the Global Times editor-in-chief urging Brazil to demolish its favellas ahead of the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio – or at the very least to give them a new paint job.

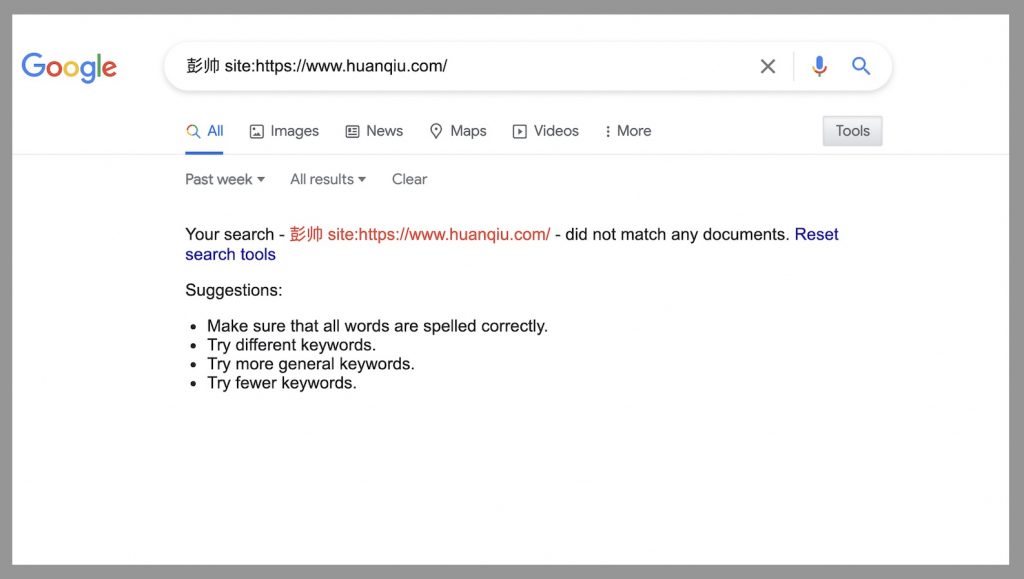

Has the Global Times in fact reported anything about Peng Shuai as Hu Xijin has taken to Twitter to argue that everything is fine? No. Nothing. This is clear from a search of the paper’s website over the past week.

A search for “Peng Shuai” and “Global Times” in Baidu turns up plenty, but the coverage all dates from 2014 and 2015, as though six years have gone missing.

A search for just “Peng Shuai” in Baidu again turns up old coverage of Peng’s tournament play, headlines from 2010, 2012, 2013, and one from 2020.

Select for the past week and there is nothing at all.

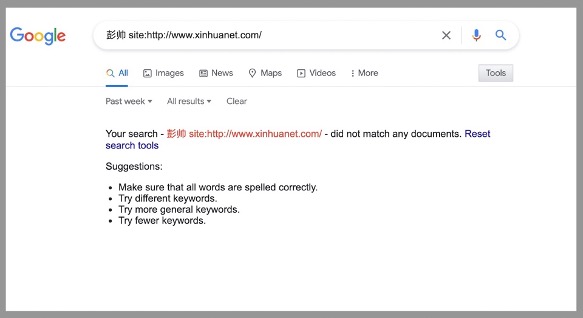

What about China’s official Xinhua News Agency? It is generally meant to lead official coverage, along with the People’s Daily, setting the standard for “public opinion guidance” and offering news releases that other media can safely run. Any reporting about Peng Shuai over the past week?

No. Again, nothing.

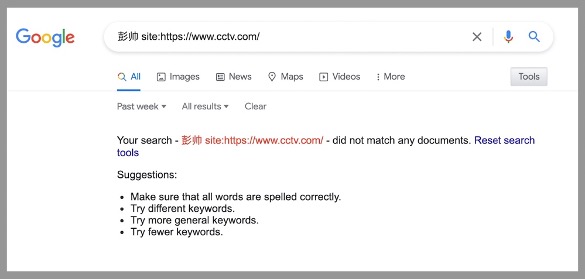

And then we have CCTV.com, the official website of the state-run broadcaster, whose CGTN has posted actively on Twitter about Peng Shuai, suggesting there is no need at all to search for her. Surely, CCTV has made its position known to the domestic audience and to the world through its powerful platform.

Once again, a search of CCTV.com reveals no coverage whatsoever of Peng Shuai over the past week.

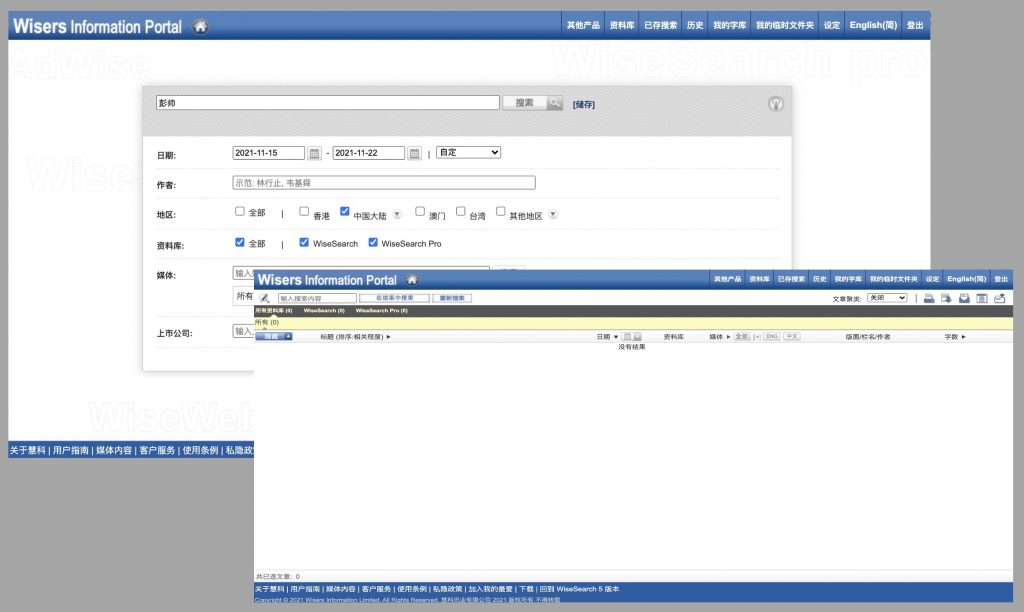

But perhaps this is the result of online content blocks? Perhaps there has been coverage offline, in Chinese newspapers? A search over the past week in the Wisers database for Chinese language media outside the PRC, in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau, turns up more than 70 reports related to Peng Shuai.

So let’s select for mainland newspapers. What do we find? Once again, total silence. Not a single result is returned for the past week using the name “Peng Shuai” in the more than 300 papers available in the database.

The crucial point we can glean from this fruitless search for “Peng Shuai” in the Chinese information space is that the tennis star is really and truly missing, despite the assurances provided by state media and associated individuals through international social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook. Which is to say that there is no real way for Peng to speak openly about the accusations she made earlier this month against a powerful political figure, and there is no space for a broader conversation, or any conversation, within the Chinese media and information environment about the implications of her case.