“Where can I buy a copy of Investor Journal? This article is so, so, so fierce!” Writing on Sina Weibo last night, Wang Xiaoyu (王晓渔), a well-known Chinese scholar and social critic, was talking excitedly about this article posted to Investor Journal‘s Sina-hosted blog.

The article — fierce indeed (and now deleted from Sina’s blog platform) — compares the “war of words” raging between Sina Weibo users and official CCP media over the issue of constitutionalism over the past week to the Democracy Wall movement in October 1978 and to democracy demonstrations in “the early summer of 1989,” a not-at-all-veiled reference, of course, to protests ahead of the June Fourth Incident.

The article goes so far as to say — in its opening paragraph — that the intensity of the row over constitutionalism has surpassed the controversy kicked up in 1989 by the World Economic Herald, the celebrated liberal newspaper shut down in the midst of the Tiananmen protests.

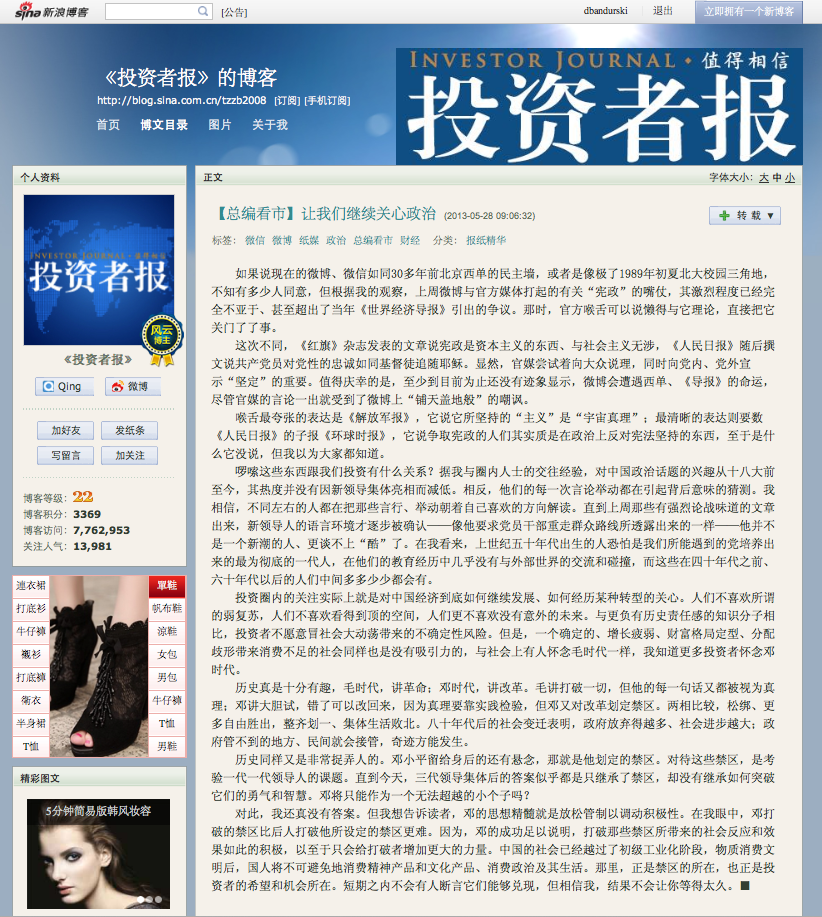

Here is what the Investor Journal blog post looked like yesterday evening, before it was removed.

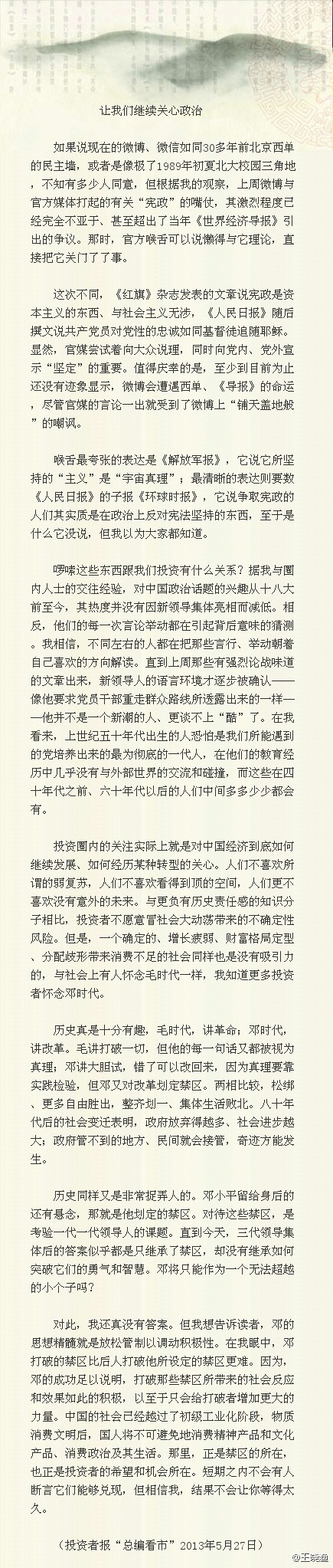

And without further ado, let’s get into the translation of the post, so all can appreciate its significance. My apologies for any inaccuracies — this was a quick job. I’ve included an image file of the original (which is still circulating on Weibo) at the bottom:

Let Us Continue to Care About Politics

Investor Journal

I don’t know whether people would agree with me or not if I said that Weibo and WeChat today are like the Democracy Wall thirty years ago, or like what we saw at Sanjiaodi (三角地) on the Peking University campus in the early summer of 1989. But the way I see it, the war of words last week between Weibo and official media over “constitutionalism” was of an intensity nothing short of, and perhaps surpassing, that we saw [in 1989] during the controversy caused by the World Economic Herald. At that time, it was possible for official mouthpiece [newspapers] to trumpet their own theories after summarily shutting the door on [the World Economic Herald].

This time things are different. The article published recently by Red Flag journal said constitutionalism is something belonging to capitalism, that it has no relevance to socialism. The People’s Daily followed with an article saying the loyalty CCP party members feel for the spirit of the Party is like the faith Christians place in Jesus. Clearly, official media are trying to voice their own reason to the masses, telling everyone inside and outside the Party at the same time just how crucial it is to remain “firm.” Thankfully, we can celebrate the fact that at least for now it seems Weibo won’t suffer the same fate as the Democracy Wall or the World Economic Herald , even though the words of official CCP media were roundly and universally mocked on Weibo as soon as they came out.

The most exaggerated voice among the [Party] mouthpieces came from the People’s Liberation Army Daily, which said that the “ism” it supported was the “truth of the cosmos” (宇宙真理). The most direct voice, meanwhile, came from the Global Times, a child paper of the People’s Daily, which said that those fighting for constitutionalism were actually those who politically were opposed to some things about the constitution. It didn’t bother to specify what these things are, but I think we all know.

What do all of these things have to do with our investments? According to my own experience, and that of others in the industry, our interest in political issues in China has not cooled down since the 18th National Congress of the CCP simply because a new crop of leaders has stepped out on stage. In fit, quite the opposite, each rhetorical move they make affects our guesswork into what’s going on behind the scenes. I’m sure that all of us, being of different persuasions, read this language [from official media] in our own way as suits our interests. Up until last week when these fierce rhetorical pieces came out and the overarching views (语言环境) of the new leadership became clear. He demands that Party members and cadres unite general public and to win people’s support (群众路线). [EDITOR’S NOTE: This was an approach pushed by Mao Zedong, and some people now think Xi’s actions signal the reappearance of a Mao-style rectification movement like the anti-rightist movement of the 1950s.] He [Xi Jinping] is not someone bringing a fresh approach, even less is he “cool.” In my view, those born in the 1950s are the most thorough generation [of believers] ever trained by the Party. Their educational experience is essentially devoid of contact and dialogue with the outside world, while those born in the 1940s and after the 1960s do have [such experience].

In investor circles the attention is actually on how exactly China’s economy will continue to develop, how it will get through a number of key transitions. We don’t like the so-called soft recovery. We don’t like reaching the ceiling. Even less do we like futures without the unexpected. Unlike intellectuals, who have a stronger sense of historical responsibility, investors aren’t willing to face the indeterminate risks of mass social chaos. But at the same time a society that is determinate, where growth is exhausted, where patterns of wealth are fixed, where discriminatory distribution creates insufficient consumption is also unattractive to us. Just as many people within society cherish the era of Mao, I know most of us investors cherish the era of Deng.

History is thoroughly interesting. In the Mao era the talk was of revolution. In the Deng era the talk was of reform. Mao talked about breaking through everything, but every word he spoke was seen as the truth. Deng talked about making big experiments, but Deng also created forbidden zones for reform. . . The late 1980s showed that as the government let go of more, society made greater progress; those areas that the government couldn’t manage, society took charge of, and miracles happened. History also has a way of toying with people. Deng Xiaoping also left much in suspense for those who came after — I’m talking about those forbidden zones he marked out. Dealing with these forbidden zones is something that has tested generation after generation of leaders since. To this day, we’ve had three generations of leaders whose only answer was to perpetuate these forbidden zones, and successors seems to lack the intelligence or courage to break through them. Will Deng and Jiang serve only as unsurpassable marks?

Truthfully, I have no answer to this. But I want to tell our readers that the heart of Deng’s thinking was about loosening restrictions and stimulating initiative. In my view, the forbidden zones Deng broke through himself were far more difficult than the breaking through by his successors of the forbidden zones he established. Because Deng’s successes demonstrate that the social reaction and impact of breaking through these forbidden areas is overwhelmingly positive, and doing so can only give greater strength to those who do break through them. Chinese society has already surpassed the early stages of industrialisation, and it’s inevitable that the culture of material consumption will be followed by consumption by the people of our country of more cultural and non-material products — the consumption of politics as well as life styles. Where there are forbidden zones, that’s where the hopes and opportunities of investors lie. No one could declare that these will be realized in the short term. But believe me, to see the results you won’t have to wait for long.

[ABOVE: The original link to the Investor Journal blog now yields a message that reads: “We’re sorry, the page you’re looking for does not exist or has been deleted.”]