As the Chinese Communist Party’s official flagship newspaper, the People’s Daily is not made to entertain, or even necessarily to edify beyond the dictates and doings of the Party itself. But let it never be said that the pages of this strait-laced paper do not disguise gems of any kind.

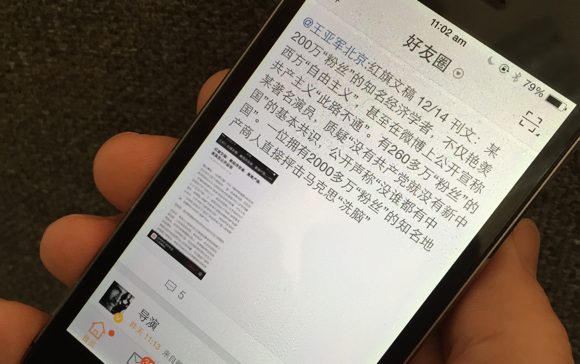

As a case in point, we’d like to share the following essay from the People’s Forum section on page four of today’s People’s Daily. The piece addresses a phenomenon we are all familiar with — wherever we are — in the age of the ubiquitous smartphone: the “head droppers,” or ditouzu (低头族), who can’t seem to extract themselves from the mobile internet.

The People’s Daily piece manages to bring together the American dystopian writer Kurt Vonnegut, the ancient Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zi (庄子), the GO master Wu Qingyuan (吴清源) and the contemporary Chinese performance artist Xie Deqing (谢德庆) to consider the deep impact the mobile internet has had on all of our lives.

So lift your chin, read, and enjoy.

“You Can ‘Drop Your Head,’ But Don’t Lose Attention” (People’s Forum)

Bai Long (白龙)

The People’s Daily

December 15, 2014

Page 4

One thing you see all the time in China is that people have become “head droppers” (低头族). Whether you’re on the underground, on the street, in a university study room or a hospital waiting room, everywhere there are people dropping their heads to look at their mobile phones. Smartphones have become like magic boxes, and like greedy hunters people are constantly on the prowl, waiting to see what rabbits will emerge from the box, so that eventually they are led deep into the gloom of the forest, where they gaze around blankly.

This forest whose boundaries lie beyond all vision is called the mobile internet (移动互联网). It is a completely new territory, and history and experience can offer us little direction where it is concerned. Experts say that from the time humankind could walk upright to about 2003, it produced around 5 exabytes of knowledge (1 exabyte equalling one billion gigabytes); but in 2015, [they expect] the digital information flowing aroudn the world to be reach 966 exabytes. When a vast sea of information appears right there on the few inches of our mobile screen, when it surrounds us ubiquitously, how can it not be a shock to our way of life?

The most severe criticism of the “head droppers” has come from heavy-hearted humanists. They believe that smartphones are destroying subjectivity, making people no longer capable of putting their full energy into things. The American author Kurt Vonnegut suggested last century in a piece of fantasy writing that in the future people with higher intelligence would be required to wear ear radios in order to address inequalities of intelligence, that every 20 seconds they would be subjected to harsh bursts of sound, making it impossible for them to think about anything. [NOTE: The writer is referring to Vonnegut’s 1961 dystopian short story “Harrison Bergeron.”] Well, today mobile phones are disturbance devices for us all. Every time a chime sounds, it’s like we must take a little break [from whatever we’re doing], whether its a nice cup of tea we’ve just made, or a moment deep in thoughtful reading. We must stop and take a look at some new bit of information.

We cannot deny that the mobile internet has brought us immense convenience. The right attitude to have is mastery of technology, accommodating the times rather than avoiding them. In fact, at any point in history, new forms of technology have been criticized for various reasons as they emerge. When printing technology made newspapers widespread, when television sets started appearing in living rooms, these voices of cultural conservatism could be heard.

Nor can we deny that so far no technology has, like the mobile internet, had such a major impact on the attention of human beings. Embracing new technology, but at the same time preserving our attention — these are the twin challenges we face.

Attention is a necessary condition of a full and healthy personality. It is also the foundation of any human cultural or intellectual pursuit. There is a story recorded in the Book of Zhuang Zi (庄子·达生) in which Confucius makes a visit to the Kingdom of Chu, and in the forest there he sees a camel bearing an old man who is using a pole to gather cicadas. He uses the device with ease, as though it is his own limb. Surprised at his skill, Confucius asks the old man if he can teach him. The old man explains that he ascertains the cicadas with his full heart and mind (一心), never looking right or left — and for nothing does he ever break his concentration on the diaphanous creatures. Through time and practice, his success came naturally. Hearing this, Confucius said to his disciple: If the will does not divert from its object, then spirit may be focused” (用志不分,乃凝于神). These words were later applied to the great Weiqi (or GO) master Wu Qingyuan (吴清源). . . For anyone and everyone who has work they must attend to, these words are worth hearing.

Smartphones are just a symbol that epitomizes our information society. The crucial question is how, in a fragmented age, we think, and how we conserve our valuable capacity to pay attention. Just 30 years ago, the contemporary artist Xie Deqing (谢德庆) completed a series of performance art pieces that shocked the world, and one of these was that every hour he would stamp a time card, and in each day he would do this 24 times, keeping it up for a full year. He wanted to use this means to remind others how modern life could be split into fragments like this.

Our lives move forward through splinters of information, and among these splinters we must find the sense of life, piecing them together into a picture of complete value — so that time doesn’t necessarily become a mottled mosaic, so that the human spirit does not crumble under waves of data. Making that happen begins with our control of how we use our own mobiles.