WHAT IS IT about the number 19? Back in 2013, Xi Jinping delivered his first major speech on ideology, in which he spoke in hardline terms about a “public opinion struggle,” on August 19. This year, on February 19, Xi Jinping visited state media before delivering an “important speech” on “news and public opinion work,” in which he said that media “must be surnamed Party” and do the Party’s bidding. On April 19, Xi Jinping let loose on the now central issue of cybersecurity, outlining strengthened internet controls and saying that a “clear and bright online space, ecologically sound, is in the interests of the people.”

Is Xi Jinping obsessed with the number “19”? All three of his “important speeches” on media and information policy have been held on the 19th of the month. The character for “9” is a homonym in Chinese of the word for “long-lasting,” seen above.

The character for “9” in Chinese is a homonym of “long-lasting” (久), and as a result tie-ups, such as contracts (or marriages), are often formalised on the 9th, 19th or 29th of the month — an auspicious sign of sustained harmony.

Is it that Xi Jinping pines for an eternal spring of ideological dominance? Does he envision an enduring Eden of the mobile internet, a garden “ruled by law,” where forms and content effloresce but no-one dares touch the forbidden fruit of knowledge?

For now, readers may file these questions away in “Arcana of the Xi Jinping Era.”

But we have another 19 of sorts. Yesterday, June 19, a lengthy article by Tian Jin (田进), deputy director of China’s State Administration of Press and Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT), appeared on page five of the People’s Daily as part of a series on the “study and implementation” of Xi Jinping’s February 19 speech on the media.

Tian’s article is of course not a Xi Jinping speech. But it is remarkable for the harder edge it gives to Xi’s already hard language on the media — and it is a very concerning indication of the depth of official resolve in tightening, expanding and re-envisioning information controls.

But first off, who is Tian Jin?

Tian, a native of Shanxi who was educated at Hunan University, has spent the past 15 years within the media control bureaucracy, first joining the State Administration of Radio Film and Television (SARFT) in 2001. Before that, he spent almost two years in Hong Kong as a senior administrative affairs official at Xinhua News Agency.

The 2015 television period drama “The Empress of China.” Just too much cleavage for SAPPRFT official Tian Jin?

It was Tian who fielded questions from reporters in January 2015 following news that the authorities had pulled the popular television series “Empress of China” to make additional cuts. Later that year, addressing a television market event in Shenzhen, Tian praised the industry for “the resounding main theme [of the Party] in their productions, and more robustly positive energy.”

[ABOVE: The 2015 television period drama “The Empress of China.” Just too much cleavage for SAPPRFT official Tian Jin?]

Tian Jin began his People’s Daily article — “Grasping the Important Position of News and Public Opinion Work” — by describing the significance, in the grandest terms, of Xi Jinping’s February 19 address on media policy. The speech, said Tian, provided “the fundamental standard in doing news and public opinion work at this new historical starting point, and offered powerful ideological weaponry in meeting the challenges on the new front lines of news and public opinion, under the new situation, and in breaking through difficulties.”

In CCP jargon, this is more or less secret code for: Unless we get a handle on the mobile-based internet and any other disruptive information technologies that might be coming down the pipeline, the Party will lose its grip on political power. And President Xi has handed us the general blueprint for total information dominance.

All of this is blandly familiar. But what really makes Tian Jin’s piece special is the way he remorselessly employs retrograde language to explain the Party’s priorities and their historical context:

News and public opinion work is an important task for the Party. Comrade Mao Zedong said that revolution relies on the barrel of the gun and the shaft of the pen, and that the Chinese Communist Party must hold pamphlets in its left hand and bullets in its right before it can defeat the enemy. Prioritising news and public opinion work is a fine tradition of our Party, and an important magic weapon that has brought constant victories in revolution, [national] construction and reform. Under the conditions of a new era, the cause of the Party faces an even more arduous and onerous task.

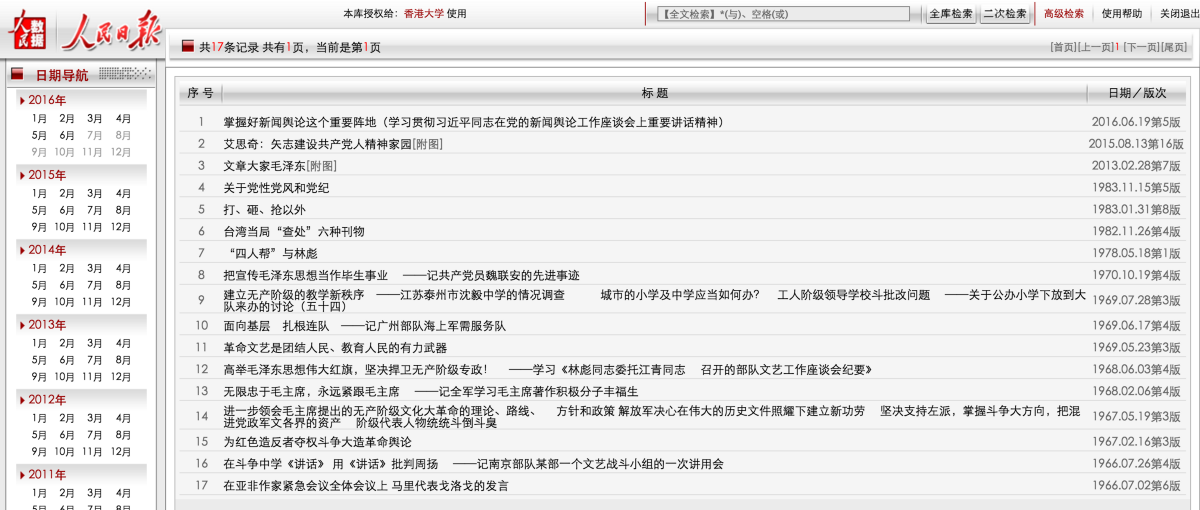

Such talk of guns and pens, of enemies and magic weapons, is the kind of hardline nostalgia we would expect to see on leftist forums in China. We generally would not expect to see such talk in the People’s Daily. In fact, the phrase “barrel of the gun and shaft of the pen” (枪杆子和笔杆子) has appeared just 17 times in the entire history of the newspaper, going all the way back to July 2, 1946. It has appeared in three articles in the Xi Jinping era, after a dormancy of almost 30 years:

1. Tian Jin’s piece on news and public opinion work — June 19, 2016

2. A profile of Ai Siqi, encouraging officials to be theory-minded and study up on their Marxism — August 13, 2015

3. A look back on Mao Zedong’s writings — February 28, 2013

Before these more recent instances, we have to go back almost 30 years to November 15, 1983, to find the last use of the phrase. In the five and a half years from May 18, 1978, to November 15, 1983, there were four pieces in the People’s Daily mentioning the phrase “barrel of the gun and shaft of the pen” — three of them in the context of roundly criticising the Gang of Four and the internal political strife of the pre-reform period.

1. “These counter-revolutionary activities strongly demonstrate intense collusion between counter-revolutionary gun barrels and pen shafts, banding together as traitors.” — May 18, 1978

2. [Mention on a list of books under investigation in Taiwan of a book called, Gun Barrels and Pen Shafts of the KMT.] — November 26, 1982

3. “Lin Biao understood that to engage in counter-revolutionary activities, he had to rely on the ‘two staves,’ namely the barrel of the gun and the shaft of the pen.” — January 31, 1983

4. “First of all, the reactionary rulers grabbed control of the seals [government power], the handcuffs [police power], the guns [military] and the pens [intellectuals], seeking to snuff out and suppress every spark of the revolution.” — November 15, 1983

When we go back beyond these four mentions in the early reform period, we have ten articles remaining, all of them published during the Cultural Revolution.

The 17 articles in the entire history of the CCP’s official People’s Daily mentioning the phrase “gun barrels and pen shafts.” The vast majority occur during the Cultural Revolution, or are used negatively in the early reform period.

Tian Jin’s extremist language continues in the next section of his article, as he piles on “ideological struggle” — an alternative to “public opinion struggle,” which Xi introduced in August 2013 — and “hostile forces,” that catchall phrase pointing to nefarious internal/external enemies of the Party.

Grasping the overall situation in the ideological struggle (把握意识形态领域斗争全局). Along with the acceleration of social transformation in our country, various tensions have grown more obvious, and ideas in society are diverse, varied and changeable — so that we see more frequent interchange, interaction and confrontation between various trends of thought. Internationally, the contest remains intense among different value systems and institutional models (制度模式), and hostile forces overseas have not relented in the plots of Westernisation and division directed against us, with no fundamental change to the status quo of a strong West and a weak China in terms of international public opinion. News and public opinion are on the frontiers of the ideological struggle, and various hostile forces are vying with us for public opinion positions, vying for people’s hearts (争夺人心), vying for the masses (争夺群众). Newspapers and periodicals, and radio and television networks, are the mainstream media trusted by the Party and the people, and they must maintain an active posture (必须主动作为), having the courage to “drive the demons out of our land” (玉宇澄清万里埃), playing the positive and upright main theme (主旋律) [of the Party], eliminating the negative impact of static and noise (杂音噪音), effectively channeling public opinion in society, and firmly grasping the initiative and leading position in the struggle in the ideological sphere.

Tian Jin (田进), deputy director of China’s State Administration of Press and Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT), unpacks Xi Jinping’s February 19, 2016, speech on page 5 of the People’s Daily on June 19, 2016.

Later on in his article, Tian speaks of the need for greater nuance in propaganda, putting out products “in forms the people of various countries will enjoy” in order to “have a positive influence overseas.” But at this point, we have spittle on our collars.

The Party’s goal is to dominate the message, both at home and abroad — and there is no need to beat around the bush. This is a life-and-death struggle for ideological dominance.

The reference to “static and noise” recalls an ideological controversy almost 12 years ago in China, when the Liberation Daily roundly attacked the idea of “public intellectuals.” That was in November 2004, after some of China’s more freewheeling commercial papers took up this sensitive issue in the wake of the August 2004 edition of the UK’s Prospect Magazine. After a snide rejection of the notion of “independent” voices — “Intellectuals are part of the worker’s class, part of the masses, and a group under the leadership of the Party.” — the Liberation Daily fumed:

Concepts like this “public intellectuals” are just static and noise, and cannot influence the main tone of our society’s public opinion. But nor can we take a casual attitude. As we face a diversified situation, it is most crucial to remain clear and firm — for only then can the leading position of Marxism be upheld, and only then can we not lose our bearing amid an abundance of ideas.

The Liberation Daily article was a worrying volley from the fringes, and it drew a great deal of scorn from many in China’s press. Tian Jin’s article is more significant. In this case, we have even denser hardline language employed by a senior media official writing in the People’s Daily — in a series, moreover, formally identified as an unpacking of Xi Jinping’s speech in the interest of putting it into practice.

Let’s go through some of the language further on in Tian’s article.

Under a section headed “adhering to the correct political orientation” (坚定正确政治方向), Tian stresses the principle of the “Party nature” of the media, which is of a piece with Xi Jinping’s insistence that the media be “surnamed Party,” and “love the Party, protect the Party and serve the Party.”

Adherence to the “Party nature” is at the core also of “strict propaganda discipline” (严格宣传纪律), a familiar media control concept in China essentially encompassing the idea that journalists must behave as the Party wants them to behave. But here, again, Tian’s hackles go up and we glimpse the fresh extremism that marks the Party’s approach to information under Xi Jinping.

We must throughout put propaganda discipline up in front, effectively enhancing firm and willing compliance with propaganda discipline . . . not offering any channel for the transmission of erroneous ideas and static and noise.

How will the Party accomplish this? Despite its grandiosity, Tian Jin’s piece differs from much propaganda claptrap in its relative specificity. We can hear in his language not just fury and determination, but an organised and directed will:

We must adhere to territorial responsibility, responsibility for [one’s] territory, ultimate responsibility for [one’s] territory (守土尽责), carrying out the strengthening of discipline throughout, strengthening channeling and management, strengthening comprehensive and strict checks — quickly discovering, firmly restraining and strictly handling certain programs that hype hot social topics, ridicule national policies (调侃国家政策), spread erroneous views (散布错误观点), advocate extreme ideas (鼓吹极端理念) and deliberately intensify contradictions, and conducting awareness education on classic problems through the entire system.

Tian is talking about amplifying the sense of urgency at every level of the media and propaganda ecosystem, and holding leaders and staff responsible for breaches the occur on their watch.

In other sections, Tian talks about “adhering to correct guidance of public opinion” (坚持正确舆论导向), and about “encouraging unity and stability, [and] emphasising positive news” (团结稳定鼓劲、正面宣传为主).

All of this is familiar. But once again, Tian is emphatic and absolutist in a way that seems remarkable. One of his sections is headed: “Correct guidance that is all-encompassing, without exceptions (正确导向全覆盖、无例外). After which, he writes:

We must connect the adherence to correct guidance to every aspect of our work, implementing it in every element, in every position, in every procedure, through every responsible person, absolutely without leaving any hidden dangers or dead ends (绝不留隐患和死角).

Moreover, we have every indication from Tian that the Party is following through on this absolutist approach to control, and that, in fact, it is just getting started:

In recent years, we have already implemented a series of policy measures in terms of the maintenance of guidance at news interview programs, entertainment programs, talent shows, legal programs, reality shows, etcetera.

Further on, in his section on “innovating management concepts, and unifying measures and standards” (创新管理理念,统一尺度标准):

Lately one focus has been promoting unification of measures and unification of standards for guidance and content management between traditional media and new media. For this, we have built a monitoring system (监看监管制度) for audiovisual programming, promoted the building of a network production and broadcast management system for online dramas (网络剧) and micro-films (微电影), introduced measures to strengthen management of overseas television dramas online, all of which have had a positive impact in regulating order in online audiovisual broadcasting, and in promoting the healthy development of the online broadcasting industry (网络视听业). The next step is the research, development and introduction of management measures for documentaries, animation and variety programmes, truly achieving [a situation in which] wherever new media technologies and businesses develop, management can develop in step, truly achieving not just control but also solid management (管得住而且管得好).

For anyone interested in hardline CCP discourse, Tian Jin’s piece offers an embarrassment of riches. It does not bode well for Chinese media or content of any kind for the foreseeable future, suggesting the Party will continue to tighten restrictions — and to make concerted changes to institutions, regulations and other mechanisms that can further this core objective.

The focus, so clear in Tian’s language, is on the challenges posed by the internet and mobile-based media. Which is why, beyond control and regulation, he stresses the need to “accelerate the building of new mainstream media (新型主流媒体), in the process raising the influence and transmission power of [the Party’s] news and public opinion work.” He talks about “actively developing and utilising differentiated, segmented and directed content across websites, Weibo, WeChat, apps and other communication channels.”

Behind Tian Jin’s language, we can hear the clarion call of Xi Jinping’s ambition — the building of a new and all-encompassing information management system, one that will allow the Party to control public opinion through the unforeseeable future of 21st century media.

The barrel of the gun belongs to the CCP, and so must the shaft of the pen, whatever the promise of new media holds. Or, rather, the Chinese Communist Party understands that to defeat the enemy of uncertainty, it must hold the bullets in its right hand and the smartphones in its left.