Ehrenburg’s essay, “Blood and Ink,” sharply criticised American correspondents who moaned that “there is nothing to see in Russia.” “We can say more accurately,” wrote Ehrenburg, “that they cannot see anything to make for flashy headlines in American newspapers. What they see is routine daily work, and yet they hunger for the sensational.”

I can tell them many things that excite us. When we see that the factories once making bombers are now manufacturing baby cradles, we become excited. When we see that the factories once making tanks are now manufacturing jugs of milk. This also excites us.

Ehrenburg voiced concern that the idea of a Third World War — which the capitalist press, he said, had “planted deep in the hearts of many Americans” — would be a self-fulfilling prophecy. “There is an old saying in France,” he wrote, “That if you talk about Christmas, Christmas comes.”

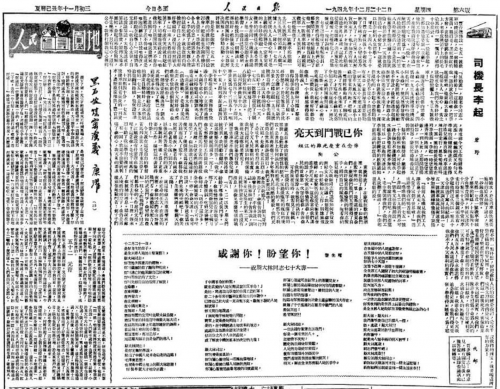

Christmas cropped up again several weeks later, as a conference of the foreign ministers of the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and France was held in New York to work out peace treaties among the nations that had achieved victory over Nazi Germany. On December 3, the People’s Daily reported that “a treaty was possible before Christmas.” Two days later the paper reported that “Christmas this year will perhaps pass with an atmosphere of harmony among the big four powers.”

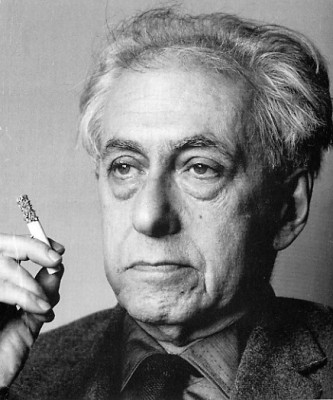

Harmony between China and the United States was shattered the following year with the chilling case of Shen Chong (沈崇), a co-ed at the prestigious Peking University who was raped by an American soldier on Christmas Eve. The People’s Daily, whose account differed slightly from that given in U.S. newspapers, reported:

On Christmas Eve (the night of December 24) at eight o’clock, a freshman Peking University student surnamed Shen emerged from a movie theatre and was followed by two American soldiers, one on her left and one on her right. They forced her into the trees of the Peiping Polo Field near Chang’an Street, where they raped her.

According to the newspaper, the crime was witnessed by another man, apparently a soldier, who notified police. It was later reported that men overhearing the struggle had tried to stop the two soldiers, US Marine Corporal William Gaither Pierson and Private Warren T Pritchard, but had been driven away.

Pierson and a U.S. consular official tried to claim that the victim was a prostitute, but she was in fact the granddaughter of Qing dynasty official Lin Zexu. Shen Chong took the stand during a court-martial hearing on January 18, 1947, and identified Pierson as her attacker, saying she had struggled with the soldier for three and a half hours.

The Chicago Tribune reported that a police physician, Dr. Kang Ho-cheng, had testified that “a healthy girl would have suffered more injuries if she resisted the attack.” Shen, the newspaper reported, had recounted her ordeal in “a soft voice”:

“My predicament was that of a mouse caught by a cat. I could not possibly injure him because a mouse cannot injure a cat. I could do nothing but cry just as a mouse shudders when caught in a cat’s claws.”

Later known as the Peiping rape case, the Shen Chong case sparked widespread anger in China and helped marshal resistance to the presence of American troops in the country. On January 8, 1947, the People’s Daily reported that “patriotic students” across the city had launched a petition campaign against the “savage acts perpetrated by the U.S. Army.”

As high-level Kuomintang officials in Beiping [Beijing] busied themselves discussing how they could ensure that the U.S. Army passed a pleasant Christmas holiday, a horrific rape was committed by American soldiers, and it occurred right on the eve of Christmas.

“A Wave of Fury,” read the article’s headline.

_______________

ON DECEMBER 22, 1949, the People’s Daily, by this time the official mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, made its first reference to Christmas since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The mention came in a poem honouring Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin on his 70th birthday. Stalin was painted as a proletarian Santa Claus bearing gifts for the downtrodden of the world.

December Twenty-First,

Is the day you were born,

And for all the people of the world it is “Christmas.”

Comrade Stalin,

You deliver precious gifts to the world,

You offer wheat and warm coats to the hungry and cold,

You call the exiles home,

You give culture to the benighted,

You liberate those who have lost their freedom!

If the Soviet Christmas invited expressions of warmth and comradeship, the American Christmas was a convenient symbol of capitalistic greed and the misery it wrought.

On December 15, 1950, poet and essayist Fang Lingru (方令孺), who had studied in the 1920s at both Washington State University and the University of Wisconsin, wrote a reflection in the People’s Daily called “How I Witnessed ‘The American Way of Life.’” Fang recalled feeling, as her steamer pulled slowly away upon her departure from America, that she would never visit the wretched country again.

Why did I have no feelings whatsoever for America? It was not without reason. For six years the American life I had seen was vulgar, prejudiced, cold, callous and apathetic, a frail soap bubble that might burst with a puff of breeze, a vast emptiness dazzling with its pretence.

In New York, Fang wrote, even the sun and air were controlled by the capitalists. Those who were wealthy could afford ample space with decent light. The poor, meanwhile, endured dark and cramped conditions.

She wrote of neighbours “wasting away from hunger” and struggling to find work. “At Christmas, their most important holiday, they can’t even return home to gather as a family,” she said.

In the 1950s, as China became mired in the conflict on the Korean peninsula, Christmas came to represent the humanity of China’s fighting force, the People’s Volunteer Army, against the cold mass of “the invading American forces” and their capitalist masters.

On December 30, 1950, the People’s Daily reported that the People’s Volunteer Army had arranged a Christmas party for American and British prisoners of war:

Even though China’s People’s Volunteer Army doesn’t believe in Christianity, the [soldiers] decorated the scene according to Christian custom. As soon as the POWs entered the venue, they were awed by the English banners, and by a pair of “Christmas trees” adorned with red candles and silver alarm bells symbolising freedom.

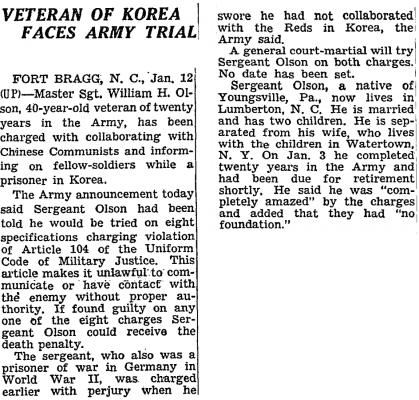

A “42 year-old” prisoner identified as Olsen was quoted by the People’s Daily as saying that his treatment as a captive by the Chinese was far better than he had experienced in Germany during the Second World War. “The Germans are Christians,” Olsen reportedly said, “but they didn’t allow us to have a merry Christmas.”