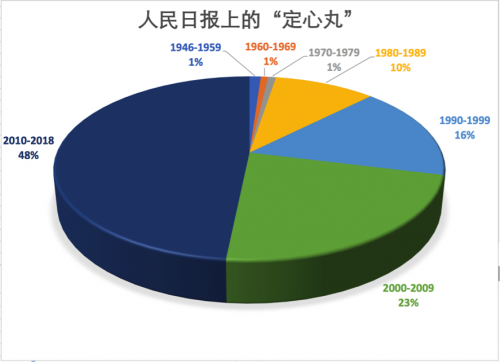

“Anxiety Pill” in the People’s Daily. The chart shows the percentage of total articles using the term in specific historical time frames.

Our look at the numbers suggests the author is correct when he concludes that the number of articles using the term “anxiety pill” have increased since 1979, and have risen substantially in more recent years, since 2010.

From 1946 to 1959, a total of 20 articles used the term “anxiety pill” in the People’s Daily, accounting for one percent of the total.

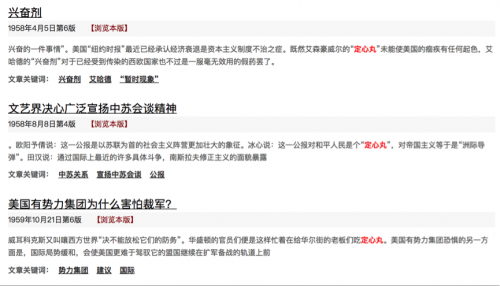

In the early part of this period, articles generally had to do with private property, but after the socialist transformation (社会主义改造) process up to around the middle of the 1950s, the meaning of the term was different. Look, for example, at these articles appearing during the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962):

The first of these is a piece that jubilates over economic troubles in the United States in 1958, when the country was hit by a recession. The piece reports that the New York Times has “admitted that economic recession is an incurable disease suffered by the capitalist system” – and that President Eisenhower’s “anxiety pill” has failed to bring relief. The second is about a communiqué emerging from Sino-Soviet talks on the arts, quoting the Chinese writer Bing Xin (冰心) as saying that the communiqué is “an ‘anxiety pill’ for peaceful people, and an intercontinental ballistic missile for imperialism.”

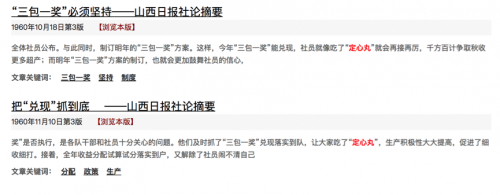

From 1960 to 1969, a total of 13 articles used the term “anxiety pill” in the People’s Daily, also accounting for around one percent of the total. Many of these have to do with adjustments to national policy in the wake of China’s Great Famine. The two articles listed below in the People’s Daily database, for example, have to do with the introduction of an incentive system for production teams that manage to record higher outputs. The second of these says that the implementation of this system has “made everyone eat ‘anxiety pills,’ and the zeal for production should increase greatly.” More zeal, in other words, means a bigger harvest—and so everyone can rest assured that their bellies will be full.

The handful of pieces published during the Cultural Revolution were essentially in service of internal political struggles and had nothing whatsoever to do with the interests or concerns of ordinary people. Between 1970 and 1979, there were 14 articles that used the term “anxiety pill,” but 10 of these appeared in 1979, the first year of opening and reform.

From 1980 to 1989, there was quite a dramatic increase in the number of articles using the term, with a total of 180 accounting for 10 percent of the total. These are all closely tied to economic reforms. Look, for example, at the sample of articles below from 1988. The first of these articles mentions prescribing “long-lasting anxiety pills” for businesses, by which it means effective reforms to the contract responsibility system, moving China further toward a market economy.

We even found one piece from 1988 that talks about the 13th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, held in October-November 1987, as offering “anxiety pills” to individual business owners (个体经营者). Interestingly, the reporter who wrote that article was Zhu Weiqun (朱维群), who would later take charge of the United Front Work Department.

After this point, “anxiety pill” enters a period of rapid increase.

In 1990-1999,299 articles, 16 percent of the total

In 2000-2009,414 articles, 23 percent of the total.

In 2010-2018 (up to November 3), 881 articles, 48 percent of the total.

This means that close to half of all articles including “anxiety pill” in the more than 70-year history of the People’s Daily have been published in just the past 9 years, and we have also seen the sharpest increase since 2016. According to the temperature standard we apply to Party media discourse at the China Media Project, we can say that “anxiety pill” has become a “warm” term, the third of our six designations for keywords (cold/tepid/warm/hot/red hot/blazing). As of November 3, the term had been used in 119 articles for the year, and we can expect it to continue strong for the rest of the year, particularly given Xi Jinping’s recent remarks.

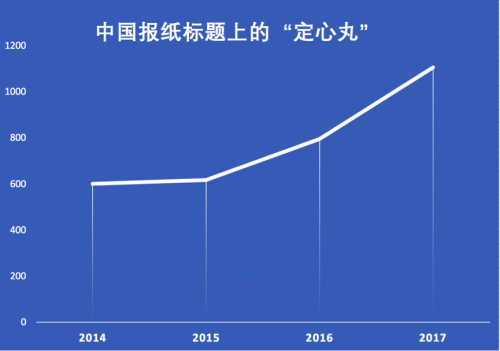

When we use the Aheading Information (前方) database of national newspapers in China, we can see a similar pattern emerging.

In 2017 alone, the term “anxiety pill” appeared in the headline of 1,109 articles. By November 3 this year, there were already 917 headlines using the term — so we can probably expect a new high, understanding of course that this is not a perfect science and there can be some variance in how the database is compiled.

What do we learn from all of these trending numbers? For many who have commented on the term in light of recent anxieties over the private sector, the trend to note is the way discursive “anxiety pills” are increasingly being prescribed by the leadership as real actions politically and ideologically take China in a direction that for many induces anxiety.

Sharing Wang Mingyuan’s ill-fated post before its deletion, Mao Guochuan (马国川), an editor for Caijing magazine, put his finger directly on this sense of disquiet and suggested several measures he would prescribe:

Our look at the numbers suggests the author is correct when he concludes that the number of articles using the term “anxiety pill” have increased since 1979, and have risen substantially in more recent years, since 2010.

From 1946 to 1959, a total of 20 articles used the term “anxiety pill” in the People’s Daily, accounting for one percent of the total.

In the early part of this period, articles generally had to do with private property, but after the socialist transformation (社会主义改造) process up to around the middle of the 1950s, the meaning of the term was different. Look, for example, at these articles appearing during the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962):

The first of these is a piece that jubilates over economic troubles in the United States in 1958, when the country was hit by a recession. The piece reports that the New York Times has “admitted that economic recession is an incurable disease suffered by the capitalist system” – and that President Eisenhower’s “anxiety pill” has failed to bring relief. The second is about a communiqué emerging from Sino-Soviet talks on the arts, quoting the Chinese writer Bing Xin (冰心) as saying that the communiqué is “an ‘anxiety pill’ for peaceful people, and an intercontinental ballistic missile for imperialism.”

From 1960 to 1969, a total of 13 articles used the term “anxiety pill” in the People’s Daily, also accounting for around one percent of the total. Many of these have to do with adjustments to national policy in the wake of China’s Great Famine. The two articles listed below in the People’s Daily database, for example, have to do with the introduction of an incentive system for production teams that manage to record higher outputs. The second of these says that the implementation of this system has “made everyone eat ‘anxiety pills,’ and the zeal for production should increase greatly.” More zeal, in other words, means a bigger harvest—and so everyone can rest assured that their bellies will be full.

The handful of pieces published during the Cultural Revolution were essentially in service of internal political struggles and had nothing whatsoever to do with the interests or concerns of ordinary people. Between 1970 and 1979, there were 14 articles that used the term “anxiety pill,” but 10 of these appeared in 1979, the first year of opening and reform.

From 1980 to 1989, there was quite a dramatic increase in the number of articles using the term, with a total of 180 accounting for 10 percent of the total. These are all closely tied to economic reforms. Look, for example, at the sample of articles below from 1988. The first of these articles mentions prescribing “long-lasting anxiety pills” for businesses, by which it means effective reforms to the contract responsibility system, moving China further toward a market economy.

We even found one piece from 1988 that talks about the 13th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, held in October-November 1987, as offering “anxiety pills” to individual business owners (个体经营者). Interestingly, the reporter who wrote that article was Zhu Weiqun (朱维群), who would later take charge of the United Front Work Department.

After this point, “anxiety pill” enters a period of rapid increase.

In 1990-1999,299 articles, 16 percent of the total

In 2000-2009,414 articles, 23 percent of the total.

In 2010-2018 (up to November 3), 881 articles, 48 percent of the total.

This means that close to half of all articles including “anxiety pill” in the more than 70-year history of the People’s Daily have been published in just the past 9 years, and we have also seen the sharpest increase since 2016. According to the temperature standard we apply to Party media discourse at the China Media Project, we can say that “anxiety pill” has become a “warm” term, the third of our six designations for keywords (cold/tepid/warm/hot/red hot/blazing). As of November 3, the term had been used in 119 articles for the year, and we can expect it to continue strong for the rest of the year, particularly given Xi Jinping’s recent remarks.

When we use the Aheading Information (前方) database of national newspapers in China, we can see a similar pattern emerging.

In 2017 alone, the term “anxiety pill” appeared in the headline of 1,109 articles. By November 3 this year, there were already 917 headlines using the term — so we can probably expect a new high, understanding of course that this is not a perfect science and there can be some variance in how the database is compiled.

What do we learn from all of these trending numbers? For many who have commented on the term in light of recent anxieties over the private sector, the trend to note is the way discursive “anxiety pills” are increasingly being prescribed by the leadership as real actions politically and ideologically take China in a direction that for many induces anxiety.

Sharing Wang Mingyuan’s ill-fated post before its deletion, Mao Guochuan (马国川), an editor for Caijing magazine, put his finger directly on this sense of disquiet and suggested several measures he would prescribe:

The true anxiety pill would be: 1) openly and clearly opposing the [political] left-wing; 2) revising the Constitution, fixing term limits; 3) reversing the verdicts in certain unfair cases against private businesses; 4) openly and clearly repudiating the Cultural Revolution. Without these steps, there is always the possibility that the ‘anxiety pill’ is actually a ‘strongman pill.’