Earlier this month, in a piece called “A Rock Star’s Fengqiao Experience,” we looked at the recent arrest of celebrity Chen Yufan (陈羽凡) and how this affair, apparently unlinked to the politics of Xi Jinping’s so-called “New Era,” is in fact disturbingly reflective of it. We can link the Mao-era “mass line” notion of the “Fengqiao experience,” which Xi Jinping has revived over the past five years, to new and intrusive forms of social management. But these trends in social management also pre-date the Xi era.

One of the key terms relevant to this “social management system,” or shehui guanli zhidu (社会管理制度), is the notion of a “gridded community management system,” or wanggehua guanli tixi (网格化管理体系). But where does this idea of “grid management,” wanggehua guanli (网格化管理), come from?

In fact, “grid management” first appeared in Shanghai in 2004. The following is a report from the official Xinhua News Agency, shared at the News Center at Sina.com, at the time one of China’s leading news portals.

The report refers to the idea of the “gridding of management” in Shanghai as “visionary thinking” (瞻性思路) by the city leadership. At that time, this project was promoted by the Party secretary of Shanghai, Chen Liangyu (陈良宇).

Does that name sound familiar?

Chen’s fall from grace in the Shanghai pension scandal in 2006, less than two years after the above news story, was one of the most prominent corruption cases of the Hu Jintao era. In April 2008, Chen was handed an 18-year prison sentence for bribery, abuse of power and financial fraud for his alleged connection to the scandal. As a member of the Politburo, he was at the time the highest-level official to be toppled in more than a decade.

What is “grid management”? In the simplest sense, it is the digitising (数字化) and informationalising (信息化) of city management at the neighbourhood and community levels.

The “gridding” (网格化) of the communal space of the city requires unified city management and digital platforms, and involves the clear gridding of the city management zone into units within a comprehensive network. By strengthening the act of patrolling — including the mobilisation of community groups like those mentioned in our article on celebrity Chen Yufan — the government is able to proactively identify and handle any problems that might emerge. Consider: This was happening in Shanghai three years before the launch of the iPhone, and at least five years before the widespread availability of smartphones made mass data potentially available to governments. Combine this “visionary thinking” with the power of data, and it’s not difficult to imagine its implications in Xi Jinping’s so-called “New Era” a decade later.

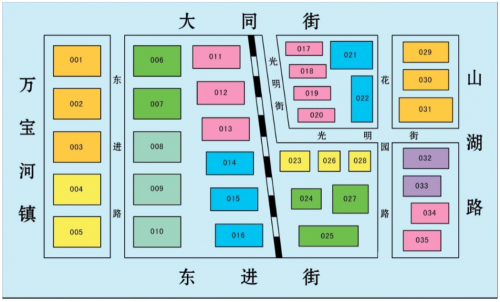

Once we know what to look for, a simple Google search can tell us a lot about this method of social management, and offer up visualisations providing a clear idea of how local governments in China are putting the idea into practice:

We can even get a picture of how “gridding” works at the micro-level of the neighbourhood and street. Here, a graphic includes a single unit of an urban grid, with colour-coded sections, the street names and sub-districts clearly labelled.

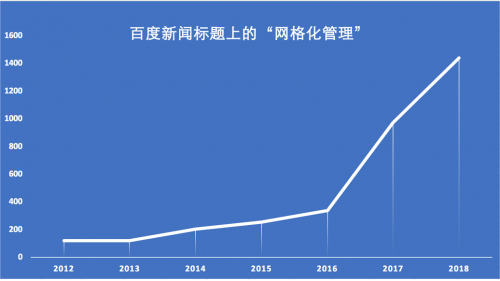

Since 2012, into the Xi Jinping era, we can see a rather dramatic rise of the term “grid management” (网格化管理) in the headlines of online news articles in China. The following graph is based on my query using the advanced search function at Baidu News.

After the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in November 2012, marking Xi Jinping’s rise to power, we see not only the continued rise of the notion of “grid management,” but also its promotion and implementation at the regional and local level across the country.

Here, for example, is a page from Tibet Daily, the official Party mouthpiece of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), dated November 3, 2014. It looks at the implementation of “gridded management” down to the district level as part of a comprehensive rollout of the approach, clearly by this point dated back over two years.

It’s not at all difficult to find similar reports of the implementation of a “grid management system” for society across the country. These reports are made in official Party publications not just as “news,” of course, but as declarations to superiors in Beijing that policies are being followed and enacted.

Here is another page from the northwestern province of Qinghai:

The examples are legion. Here we have another from Inner Mongolia:

And as we move into 2017, we can already begin to glimpse these gridded systems as they are “upgraded,” making use of digital monitoring technology. The following image is of Minhang Daily, the official publication of Shanghai’s suburban district of Minhang. The headline announces that “Version 3.0” of the city’s grid management system has now gone online.

Coverage of the gridded management system in Minhang Daily was also shared on the Shanghai channel of People’s Daily online. That coverage included images, shared through the official WeChat account of Minhang District (@上海闵行), of the “Grid Management Control Center” (网格化中心).

Even tourism destinations now apparently have their own grid management “work stations” to ensure the comprehensiveness of the system.

Once the “gridding” process is designed and implemented, patrols and data gathering in these areas can be coordinated. This is where the mobilisation of community organisations comes in as part of the Party’s process of mass organisation, which harkens back, as we wrote previously, to Mao Zedong’s political method of the “mass line,” or qunzhong luxian (群众路线), and to ideas such as the “Fengqiao experience.” So these political ideas and grid management intersect with such groups as the “Chaoyang Masses” (朝阳群众), the “Haiding Internet Users” (海淀网友), the “Xicheng Aunties” (西城大妈), the “Fengtai Advising Squad” (丰台劝导队), and of course the “Old Neighbours of Shijingshan” (石景山老街坊) — the group that informed on rock star Chen Yufan.

To offer a further example, there is the story CMP reported last month about how Zhou Chen (周辰), a journalist at Caixin, had revealed in a tell-all account on the media’s website that she had been intimidated by local police in the city of Quanzhou, in coastal Fujian province, as she attempted to report on a chemical spill at a local oil port.According to Zhou’s account, she went to bed early on November 11 after filing her news report. She was in bed when she heard the sound of a keycard opening the door of her hotel room. Four men wearing police uniforms entered her room and asked to see her identification. They claimed to be conducting searches for prostitutes. One officer, said Zhou, told his deputies to search the toilet and balcony. They never produced their own identification. After the men left, the hotel service desk apologised to Zhou, saying police had demanded a copy of her keycard.When you understand China’s grid management system and how it operates, you can understand how this female journalist carrying out her professional obligation to conduct what in China we call “supervision by public opinion” (舆论监督), or monitoring through media coverage, would come under the shadow of the “grid” wherever she decided to stay in the course of reporting the story of the chemical spill. And under such as system, those personnel operating the grid management would be compelled to act.

The term “grid management” is a neologism in China, but it is something that could also be found in ancient times. The so-called “Baojia system” (保甲制) developed in China during the Song dynasty in the 11th century. Chinese society was divided under this system into jia (甲) consisting of 10 families, and 10 jia combined to form a single bao (保). Each jia had a leader, and its bao had a leader. This was essentially a militarisation of society in which control was exercised at every level.

The method was employed again in the 1930s, this time by the Kuomintang party as it encircled the base of the Chinese Communist Party in Jiangxi. The strategy was to tighten the noose around the neck of the Red Army, eliminating the threat they posed.

China’s 21st century grid management system seems to operate on the premise that Chinese society is a threat to itself.