China Newspeak

Parallelisms for the Future

“Parallelism,” or paibi (排比), is a rhetorical method that when used with appropriate measure can strengthen an article, but when used carelessly can have exactly the opposite effect. This is the front page of the March 4, 2019, edition of the Study Times newspaper, published by the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party, which just this month was upgraded to a central-level news unit.

The Study Times article, pictured here, totals 6,399 characters, and it makes use of 42 parallelisms, or paibiju (排比句).

To use the unique lingo of Chinese Communist Party media, this is what we call a “response article,” or fanyinggao (反应稿),” a kind of formalized exercise in responding to the instructions or ideological demands of one’s superiors. The fanyinggao can be regarded as one of a number of unique “genres” of Chinese Communist Party writing. In this case, we have a “response article” from a group of young Party cadres taking a study course at the Central Party School’s Chinese Academy of Governance (国家行政学院), and they are responding to a speech President Xi Jinping gave to mark the opening of the course.

As dictated by tradition and by the nature of the genre, such “response articles” generally are, and in fact must be, very enthusiastic (热烈).

This response tells us that the students, “harboring a mood of incomparable veneration” (怀着无比崇敬的心情), listened to the “important speech” of General Secretary Xi Jinping, that “[their] morale was boosted in no small measure, [they were] educated in no small measure, and [they were] spurred on in no small measure.” For those unfamiliar with the mechanics of the “parallelism,” it is premised on exactly this sort of repetition, which generally occurs in groups of threes. So in this construction, we have a repetition of “in no small measure,” or “deeply receive,” like this:

Deeply receive A, deeply receive B, deeply receive C

深受鼓舞、深受教育、深受鞭策

The Party School pupils praised highly the General Secretary’s “profound thoughts on history, his deeply-layered theoretical implications and the deep hopes [he] entrusted.” There was, the students noted, the “theoretical hue that keeps abreast with the times,” and the “epochal discourse of dialectical wisdom, which directly faces and assumes practical responsibility,” and “the sincere and guileless ethos of the leader.”

They were not finished.

The General Secretary “stood tall and took a broad vantage, with a manner of full responsibility as a leadership paragon, evincing the personal charisma of the nation and the people, dedicated to the cause of the country, dedicated to the Party and its historic obligations.”

Everyone affirmed that they would actualize in their speech and action the “political character, value demands, spiritual horizons and personal integrity” inherent in Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism With Chinese Characteristics for the New Era — this being Xi Jinping’s developing banner term, his personal brand, which in recent months has been trying its utmost to condense itself into the transcendent “Xi Jinping Thought” (习近平思想). They would apply this lofty thought and all it represents in their attitude, and in their work.

The language of parallelism here is in fact so dense that it is a tall order to accurately render in English. But perhaps readers get the idea.

In this one article alone there are 42 parallelisms, striking like a deafening chorus of drumbeats. One’s feeling in reading the piece is strange, to say the least.

Of course, reading such absurdly lofty language, how can we not then rush off in search of the Xi Jinping speech that inspired this “response article”? We can find the partial text of the speech published on the front page of the March 2 edition of the People’s Daily.

The full-text version of the speech is not available, unfortunately, but we can glean the general content from the report above. As it turns out, the speech itself seems to have been full to the brim with parallelisms. The report here totals 2,900 characters, and it makes use of no less than 24 parallelisms.

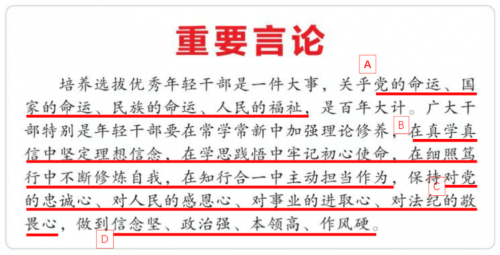

If we look just at the brief summary of the text provided at the top of Study Times, to the right side of the masthead, we can get a feel for the sheer density of parallelism deployment. I’ve marked the parallelisms in red:

in this block of text, just 175 characters in length, four parallelisms are used, accounting for 102 characters. The ardent love the speechwriter has for the parallelism comes alive on the page.

The speechwriter is not Xi Jinping himself, naturally. Since rising to the office of general secretary in 2012, Xi Jinping has delivered countless speeches. All of these speeches are written by special teams of speechwriters. In most cases, when a visit is made to a particular department it is that department’s responsibility to prepare the speech. So in this case, with the speech delivered to a group of young cadres at the Central Party School, we can suppose that the speech was prepared by the speechwriting team of the Organization Department (中组部) of the Central Party School.

Still, Xi Jinping would have seen and approved the draft, and we can be sure that no specialized terminologies, or tifa (提法), of which he did not approve would appear in the text. Furthermore, we can sure that stylistic flourishes of which he does not approve could not be allowed to appear again and again, and again, and again.

It is my observation that in the eight years since Xi Jinping came to power, his use of parallelisms has been steadily on the rise. This is particularly true since the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in November 2017. So it is probably more accurate to say that the speechwriter or speechwriters in this case merely recognized Xi Jinping’s fondness for the drumbeat quality of the parallelism.

There is immense guiding power in this rhetorical preference. After March 4, every edition of the Study Times has felt obligated to publish a “reflection article” about the March 1 speech. Aside from the March 4 piece, I have read three others, published on March 6, 8 and 11.

This is truly an actualization of the ancient saying: “Whatever is favored at the top, must cause a fever down below” (上有所好, 下必甚焉).

The March 6 piece, written by Xu Lanbin (徐兰宾), is called “Constantly Improving Ourselves, Raising Our Capacity for Action” (不断修炼自我 增强担当本领). It totals 2,131 characters in length, and at six points repeats parallelisms used in Xi’s speech, while offering up 16 more parallelisms not appearing in that speech– for a grand total of 22. So we have, for example, talk about how loyalty and belief (in the Party and its leader) “are concrete, are not abstract, arise from the inner heart, are not floating on the surface, are resolute, and do not emerge all in a moment.”

是具体的、不是抽象的,是发自内心的、不是浮在表面的,是坚定不移的、不是一时兴起的

Moreover, loyalty and belief must “be actualized in speech and in action, be evinced drop after drop, running through one’s life.”

落实到一言一行、体现在一点一滴、贯穿于一生一世

And finally, loyalty to the Party must be “internalized in the heart, planted in the soul and enter the bloodstream.”

内化于心、植入灵魂、融入血脉

All of this is to say that one must, well, be loyal. But more than this, there is a ritual quality to such expressions of loyalty. The parallelism, like the drumbeat, is about the rhythm, music and dance of loyalty. Although, aesthetically speaking, that may be too generous in this case.

The March 8 piece, written by Liu Wei (刘伟), is called “Strengthening Scientific Theories to Arm and Foster a New Generation of Successors” (加强科学理论武装培养新时代接班人). That piece has 8 original and borrowed parallelisms. He mentions, for example, that “Xi Jinping Thought” is “the most important teaching, most authoritative foundation and most fundamental content” of Marxism for the twenty-first century. Then there is the March 11 piece by Liu Yuan (刘渊), “Strengthening Study is the Political Responsibility of Party Members and Cadres” (加强学习是党员干部的政治责任). The piece totals 1,507 characters and includes 13 parallelisms, all of which are apparently original. Liu writes about the need, during study of “Xi Jinping Thought of Socialism With Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” to emphasize the study of the banner theory’s “scientific nature, modern nature, people nature, practical nature and worldly nature” (科学性、时代性、人民性、实践性、世界性).

And so, may I add to the chorus of parallelisms that we, at this point in China’s history, in this New Era, assiduously follow the New Era, ardently love Chairman Xi, and abundantly employ the parallelism. But forgive me. Writing up to this point I’ve perhaps been infected by spirit. What I wish to say is, that all of those people using parallelisms so lavishly will probably become, before too many years have passed, our new city secretaries, our news provincial Party secretaries, our new Central Committee members, and our new Politburo members.

What can their temperament and the style of their language tell us about our future?