“A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” declares Shakespeare’s Juliet, rejecting the notion that she and her lover should be torn asunder by the feud between their two houses. “‘Tis but thy name that is my enemy,” she says.

These days, names matter deeply in China. In an article published on June 15 in the official Party journal Seeking Truth (求是) and given the most prominent treatment possible on the next day’s edition of the People’s Daily, Xi Jinping declared that China’s cultural confidence, or wenhua zixin (文化自信), arises from three great cultural traditions: “Our cultural confidence is confidence in the organic integration of a culture of socialism with Chinese characteristics including China’s excellent traditional culture, revolutionary culture and advanced socialist culture.”

In practice in recent days, acting on this sense of “cultural confidence” means pushing a revolution in place names, expunging names that are excessively foreign, exaggerated, strange or redundant. When it comes to the West, in particular, it is about clearly distinguishing between the Montagues and the Capulets, between us and them — and so, out with the Hollywoods, Viennas and Victorias.

In December 2018, six Chinese ministries jointly issued a document called “Notice from the Ministry of Civil Affairs and Five Other Departments on Disposing of and Rectifying Irregular Place Names” (民政部等六部(局)关于进一步清理整治不规范地名的通知). The document stipulated that by March 2019 a list of so-called “irregular place names” should be determined and created. We are now beginning to see the process of “rectification” taking place in China.

Recently, the local civil affairs office in Hainan released its own “List of Irregular Place Names Requiring Rectification” (需清理整治不规范地名清单), demanding that place names in the province must be changed if they are “exaggerated” (大), “Western” (洋), “strange” (怪) or “repetitive” (重). Classic examples included places like “Victoria Gardens” (维多利亚花园), “Sunshine Baroque District” (阳光巴洛克小区), “Vienna Hotel” (维也纳酒店), and the “Diaoyutai Mansions” (钓鱼台别墅). All such place names must undergo a process of “renaming” (更名改姓).

Chinese media have also reported that structures such as bridges are being renamed. In Fujian province, for example, bridge names that include the word “big” or “mega” (大), are being downsized if they are not sufficiently large. This means that the names “Dongfeng Mega-Bridge” (东风大桥), “Meixi Mega-Bridge” (琯溪大桥) and “Nanshan Mega-Bridge” (南山大桥) will all have to be changed in light of the clear prohibition against “deliberate exaggeration of names” (名称刻意夸大). In these specific cases, then, the structures will be renamed simply “Dongfeng Bridge,” “Meixi Bridge,” and “Nanshan Bridge.”

“SOHO” as the name of a commercial complex has been deemed under the campaign as “weird and bizarre” (怪诞离奇). And even using letters of the English alphabet to denote buildings within residential complexes, with designations like “Block A” (A座) and “Block B” (B座), has been deemed unacceptable in places like Xi’an.

The city of Wenzhou in Zhejiang province has reportedly gone into something of a fever over place name changes. “European City” (欧洲城), a property complex, has been renamed “Aidengqiao District” (矮凳桥小区). “Central Park,” apparently too clear a reference to the famous park in New York City, has been renamed “Hongxi Garden.”

This nationwide purge of names could in fact have unforeseen consequences in a number of areas, such as for citizen ID cards, residential registration and even real estate registration. One chat thread on China’s Zhihu platform this month shared an official notice from Hainan on the necessary name changes and asked: “Is the name of your residential area safe?” Another post last Friday analyzed various place names, particularly for residential districts, as well as company names, and suggested that the implications of this movement from the top could be enormous if it is taken at its word.

One Chinese internet user ridiculed the name-change policy by creating a table showing the typical Chinese translation of foreign place names like “Queensland,” “New York” and “Red River Valley” alongside literal translations from English to Chinese, resulting in humorous variations such as the English-language “Hollywood” becoming “Jilin,” the same characters as China’s northeastern province of Jilin.

Jokes aside, the announcement of the national measures at the local level has already created a great deal of confusion, not least among hotels and other businesses making use of names that might be regarded as too Western.

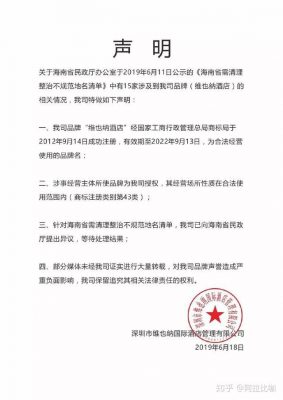

After Hainan province released its official notice regarding name changes, seen below, the local “Vienna Hotel” made its own statement through its official Weibo account making clear that its name in fact is a registered trademark, successfully registered with the Trademark Office of the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, and was legally used.

Reached subsequently by a reporter for China News Service, Shi Qingli (石清理), deputy head of Hainan’s provincial office of civil affairs, clarified that as a trademark in this case, “Vienna” had not being used as a place name and so the designation “irregular place name” did not apply. But the confusion is sure to continue as the campaign unfolds.

A commentary on the name changes at China Business Online said: “Will this broad demand for a purge really be able to raise our sense of cultural self-confidence, and bring results in regulating place names? I’m afraid we’ll just have to wait and see.”

“Ultimately, cultural self-confidence isn’t something that emerges from restrictions. Real cultural confidence should mean not viewing outside cultures with a sense of fear and foreboding.”