This week the producers of the much-anticipated Chinese war epic The Eight Hundred announced through the film’s official Weibo account that its July 5 release had been cancelled. While the statement said that a future release date would be forthcoming, the news was quickly understood to signal that the film’s journey had ended before it began.

The film almost certainly fell afoul of unspecified authorities and other influential figures with the Chinese Communist Party because it depicts the heroism of soldiers in the National Army during the 1937 Battle of Shanghai — at a time when China’s ruling Nationalist party was allied with the Communist Party to resist the invading Japanese. Films in China dealing with this period of history generally emphasize the actions and sacrifices of the Communist Party, and downplay the role of the Nationalist party, a bitter enemy during the civil war that followed.

The film’s fate has angered and disappointed many Chinese, for whom the story of Xie Jinyuan, the famous commander of soldiers holed up in Shanghai’s Sihang Warehouse, is an inspirational example of patriotism that should transcend petty ideology.

The following is our translation of one post to WeChat that makes the sense of disappointment very clear.

________________

This Age of Ours Doesn’t Deserve the Heroism of Commander Xie

As I was browsing through Weibo this morning, I saw the news that the July 5 release of Director Guan Hu’s film The Eight Hundred had been cancelled — which means that the film has been formally blocked, and will now sink beneath the waves.

Ever since the cancellation of The Eight Hundred’s credentials as an opening film of the Shanghai Film Festival, I had some sense of foreboding about the film’s destiny. But actually coming to this day I still can’t help but feel a bit hurt.

For the vast majority of Shanghai people, the Sihang Warehouse (四行仓库) on Suzhou Creek is a name that can’t be wiped from our memories.

It was around the time I was in primary school that I read the story of the 800 hundred fighters in the publication Shanghai Stories (上海故事), which was popular at the time — and the way the regimental commander Xie Jinyuan (谢晋元) and the 400 men under his command stood alone constitutes my earliest impressions of the concept of heroism.

Decades have past now, and countless American-style heroes have crossed the screen and entered the entered the minds of the Chinese people, but there there have perhaps been no Chinese heroes of truly international influence.

This is one reason I felt really excited when I learned that Guan Hu’s film The Eight Hundred would be screened, and that it would, no less, be the opening film of the Shanghai International Film Festival.

But as everyone now knows, it was changed out on the spot on June 15, and then the July 5 screening was also cancelled completely. We heard all this claptrap about “technical reasons,” and how “negotiations are underway,” when everyone knows that the real accusation here was that the film “used fragments of history to disguise the basic truth of history” (用历史碎片掩盖历史的本质真实), and that it “showed signs of deviating from historical materialism” (偏离历史唯物主义的创作倾向).

What a joke this is. Is history not always formed from fragments? If we cannot even admit the fragments, or we are unwilling to face them, what kind of historical truth can we speak of at all?

But I’m afraid it’s not quite fair either to heap all of the blame for the fate of The Eight Hundred on the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT). As a film bound for the cinema, The Eight Hundred passed examination long ago, and it had received its permit for cinematic screening.

The reason the film ultimately cannot be seen by audiences, I’m afraid, has to do with interference from all sorts of mysterious actors we generally don’t see — from “old leaders” and “old cadres,” from “___ Friendship Society” and “____ Association,”

These people generally engage in no productive activities of their own, but just eat and drink all day, and then split hairs and nitpick. If you make a film about the National Army fighting the Japanese, they will pipe up and say you are combining historical fragments and have a hidden agenda. If you film something about the Communist Army fighting the Japanese, and if it depicts a victory, they’ll pipe up about how you are making an “anti-Japanese drama” that over-emphasizes heroism and is not sufficiently objective. (If you don’t believe me, just go into the BBS chatrooms and see for yourself all of the criticisms there from old cadres over the Drawing Sword series).

And if your film depicts defeat at the hands of the Japanese, this of course is even worse. How can you spread such a spirit of defeat?

The battle by the “eight hundred fighters” at the Sihang Warehouse on Suzhou Creek went on for four days and four nights, but the victory and heroism notwithstanding, it was but a tiny and relatively insignificant part of a much greater war.

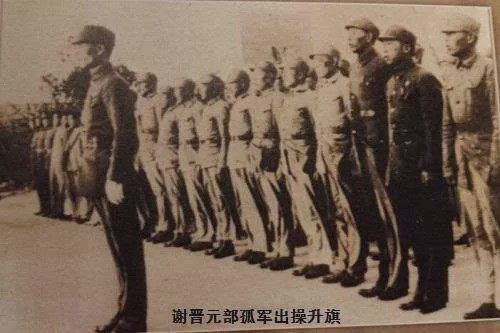

The reason why Xie Jinyuan and the 400 fighters under his command (aside from the handful of turncoats who in the end murdered Xie) are revered as true heroes in the hearts of generation after generation of Chinese is because, more importantly, Xie and his regiment remained intact [and a source of morale] for the next few years even while imprisoned in the foreign Settlement.

Without heavy weaponry, boxed in on all sides, refusing all forms of compromise and capitulation, they persisted day after day with training and raising the flag, even in the face of pressure on all sides, maintaining the discipline and dignity of soldiers.

This unswerving determination in the face of desperation became an inspiration for the whole of China at that time. It was written into song, inspiring young people to join the war to save the country: “China will not fail, China cannot fail, just look at national hero Commander Xie!”

But today, when at last some are willing to invest vast resources of money and time to properly tell this episode in history through a film, it still faces this irrational and ridiculous accusation of “historical fragmentalism” (历史碎片论). It suffocates one to speechlessness.

Saving Private Ryan told the story of how, when Americans landed on the beach in Normandy, in a shower of bombs and bullets, eight people did their utmost to save a single man, and none of you said this was “historical fragmentalism.” Hacksaw Ridge told the story of a soldier who refused to bear arms and yet saved others on the battlefield, and none of you said this was “historical fragmentalism.”

But today, people go and tell this story of how more than 400 Chinese sacrificed out of deep love for their country, and you say it is “historical fragmentalism,” that it should not be screened, that it cannot be screened, that it is not permitted to be screened. Actually, I don’t think any of these people who nitpick over The Eight Hundred would actually have the courage to take up arms and sacrifice their lives defending our country if it came again to such a moment of foreign aggression.

So in the end, The Eight Hundred will not be shown. . . .

Goodbye, The Eight Hundred. In this dog shit age of ours, we don’t deserve such a hero as Commander Xie.