For months now, fires across Australia have drawn the attention of the world, demanding people sit up and take notice of climate change and ecological crisis as well as hard questions about disaster response and readiness.

Meanwhile, in the Chinese social media space, an article comparing Australia’s unprecedented crisis to a major forest fire that occurred in China in 1987 itself fanned a wildfire over the weekend – raising questions about factual news reporting over self-aggrandizing propaganda.

The article, called “Without this Australian Fire, I Wouldn’t Know the Awesomeness of China 33 Years Ago!” (没有澳洲这场大火,我都不知道中国33年前这么牛逼!), characterized the 1987 Daxing’anling Wildfire, a devastating tragedy that had bitter lessons for China, as a moment of great heroism. All of the failings, pain and loss of the 1987 fire were twisted in the article into evidence of the “awesomeness of China 33 years ago,” contrasted with the supposed incompetence of the Australian government.

Despite the distressing level of ignorance the article showed toward history, it quickly attracted more than 100,000 views, and an image from the backend of the WeChat platform shared in private chat groups showed that by Sunday afternoon the article had been read 23 million times, and “liked” 300,000 times. These numbers are still climbing.

As a researcher of journalism and mass communication, I am familiar with the 1987 Daxing’anling Wildfire because the reporting of this story was a major event in Chinese media history. I still remember sitting in a classroom at Peking University and listening to news editors who had been involved in the story discussing the event.

A Human Disaster

On May 6, 1987, Daxing’anling prefecture in China’s northeastern Heilongjiang province experienced the most serious large-scale forest fire in the history of the People’s Republic of China. The fire raged for close to a month, swallowing up more than a million hectares of forest, a fifth of the total forest area in the prefecture. Close to 200 lives were lost in the fires, and more than 50,000 people were displaced.

On May 14, after the fire had raged for a week, the China Youth Daily newspaper sent a reporters to the scene to report the story. China Youth Daily, a paper published by the Chinese Communist Youth League, had substantial credibility and influence at the time. Before the paper’s journalists set out for Heilongjiang, they made a solemn promise to themselves: “We must remember not to take this tragic song and sing it as a hymn of praise!”

Why would they make such a promise? The reason, as the newspaper later made clear in its own summary of its reports, was that up to that time disaster reporting in China had been all about “handling funerals as happy events, greeting small misfortunes with small hymns, and treating major tragedies and great victories.”

“In the magical writings of journalists, the catastrophe often becomes a triumph of communism,” they wrote. “This was at the time the entrenched way of doing things in disaster reporting.”

But in the new climate of reform and opening, as respect grew for the value of factual reporting, a number of aspiring professional journalists were unsatisfied with this way of working. Yang Lang (杨浪), the domestic affairs editor at China Youth Daily responsible for the Daxing’anling reports, said at the time: “Everyone recognizes that a disaster is a disaster. Turning a disaster into a triumphal hymn is heaping disaster on top of disaster.”

Following these principles, journalists on the front lines in Daxing’anling went in search of the facts and tried to report the truth. Through the reports they filed, we saw clearly that the origin and spread of the fires had much to do with local officials and with bureaucratic work styles. We saw how local country leaders in the area of the fire had sent out truckloads of people to sweep and tidy up the streets to ready them for visiting officials from Beijing, even as the fires were raging. We even saw, amid the rubble of the county seat of Mohe, a single red-brick building standing alone, miraculously saved from the devastation. This was the home of the county chief and the fire department head, and local residents had told reporters that the home had been spared because the fire department head had dispatched fire trucks and a bulldozer to the scene to protect it.

These reports, the newspaper said in its own assessment, relayed to the public with a deafening sound that this was not just a natural disaster but a human disaster (人祸). “This is us—our severe bureaucratism and our rigid system have made us bureaucratic. Even as we are spared, this fire consumes us.”

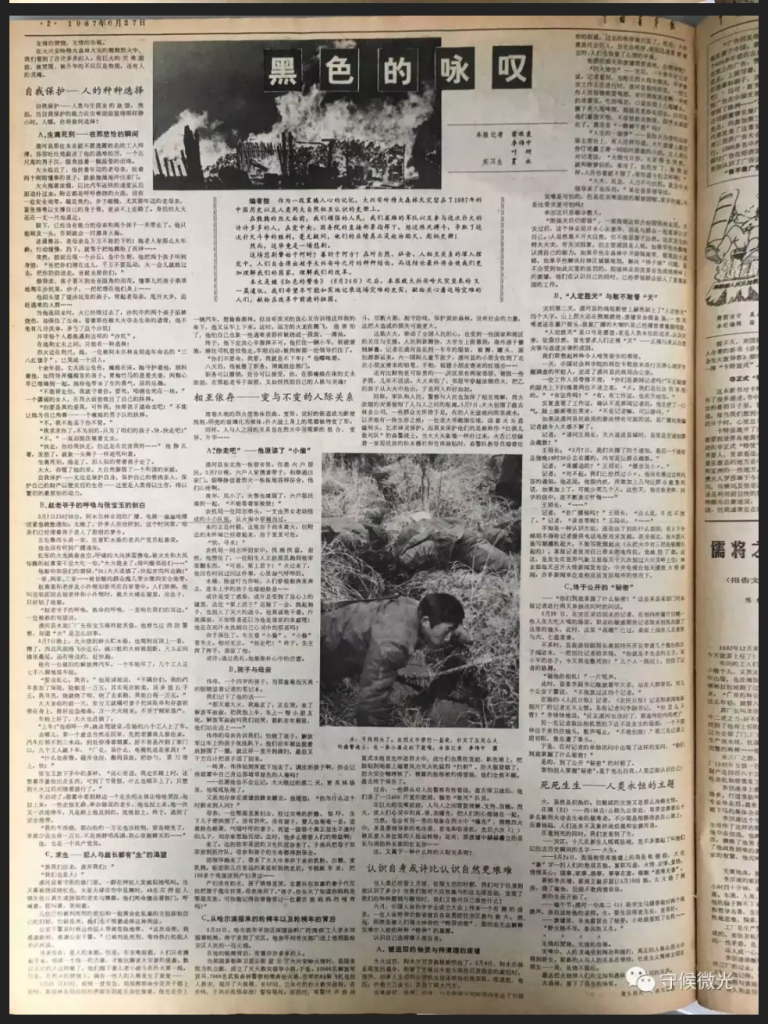

The China Youth Daily series contained three reports in all. The headlines were: “The Red Warning” (红色的警告); “The Black Sigh” (黑色的咏叹); and “The Green Sorrow” (绿色的悲哀). People referred to the series at the time as the “three color reports” (三色报道). They were widely praised, and they earned the newspaper a special award that year for best national news reporting.

One reader in Hubei province wrote a letter to China Youth Daily saying: “In the past, I always thought that journalists in our country were just in the business of pretending everything is fine, but after reading these reports I strongly feel you reporters are worthy soldiers of our times.”

In Chinese media history, the “three color reports” occupy an extremely important position. They are a milestone in disaster reporting, marking the return of disaster reports to the plane of factual reporting, respecting news values.

In fact, China Youth Daily was not the only newspaper at the time to report the Daxing’anling fire in a new spirit of thoughtfulness. Even the Party’s official People’s Daily published reports of this kind. As veteran People’s Daily journalist Zhu Huaxin (祝华新) has recalled, “the People’s Daily published 64 consecutive news reports and commentaries [on the fire], and within one month 22 news articles on the fire appeared on the front page.”

One of these reports directly questioned the idea that the disaster had been inevitable: “Many facts suggest that the fire was not a natural disaster whose containment was beyond our powers, and that this terrible, heart-wrenching misfortune should not have happened; or if it indeed it had to happen, it should not have resulted in such calamitous losses.”

The People’s Daily also addressed the question of the red-brick house belonging to the country chief and the fire department head. Journalist Wei Yanan (魏亚南) filled in a key detail of this story – that two homes to the right and left of the chief’s red-brick house had been demolished in order to help protect it.

A disaster is a disaster, as Yang Liang said. And turning a disaster into a hymn of praise is heaping disaster on top of disaster.

Reporting Against the Odds

Under the circumstances of that time in China, it was not easy to make breakthroughs in reporting. While there was talk of the need for liberation of thought, there were also of course very real restrictions and difficulties to work through for news media.

Jia Yong (贾永), a journalist who took part in reporting at the time as an intern at China Youth Daily, later continued to work as a journalist, serving for a time as director of the People’s Liberation Army desk at the official Xinhua News Agency. He later said in a piece looking back on the Daxing’anling fire that in fact the whole reporting process was extremely difficult, because many local leaders and offices worked with a “news control” mentality.

But the China Youth Daily reporters did not give up in the face of these restrictions. “With the exception of Lei Shumai (雷收麦), who was almost 40, the other three of us were young, had experience reporting through adversity on the front lines, and we were up to the challenge,” Jia Yong said. “We worked hard and with full confidence to get first-hand materials – at the scene of the fire, at the cemeteries, in the ruins, from local broadcasters, hose operators, bulldozer operators. During the day we toughened our skins and visited local government offices, and at night we were together with those who had been displaced by the disaster, sleeping together in cold tents with 40 or more people.”

Jia Yong said they felt they had to face danger and difficulty to get to the story “in order to protect the people’s right to know about this major event.” And their efforts were repaid: “More and more affected people who at first did not dare voice their anger opened up to us and told us the real situation,” he said.

Ye Yan (叶研), a reporter who later won China’s Fan Changjiang News Award, recalled that he had photographed a group of people at a local dining hall eating a meal together, and as a result was stopped in the road by a group of about 20 officials, including the head of the tourism office. He and several other reporters we set on and beaten by the group. “It was nothing for them to attack people,” he said. “And we were taken in by the Public Security Bureau for two days of questioning.”

After more than a month in Heilongjiang, the journalists returned to the newsroom to write their stories. This was at the height of the hot summer in Beijing, and an article in China Youth Daily later recalled the lengths the reporters had gone to to finish their stories. “Lei Shumai and Jia Yong were living in an underground room near the China Youth Daily newsroom that cost 35 cents a night, and together they consumed 40 bags of instant noodles. To make sure they didn’t have stomach problems, Jia Yong used a grain coupon to buy five kilograms of garlic.”

Twisted Histories

The WeChat public account that ran “Without this Australian Fire, I Wouldn’t Know the Awesomeness of China 33 Years Ago!” this past week is called “Youth Courtyard” (青年大院). In fact, this is the new name for an account that was previously shut down on the platform.

If we click into the “Youth Courtyard” account and go into the information section, we can see that the operator is “Beijing Fuguang Yuejin Cuture and Media Company Limited” (北京浮光跃金文化传媒有限公司). And when we click the name of this company we find that the account is the new name for the previous account “90s Tonight” (今夜90后). In fact, it does not really hide this fact. In fact, at the top of the article itself and in the subhead, you can clearly see mention of “90’s Tonight.”

For some readers, this may not ring a bell. Others will know that “90s Tonight” is the same outfit that published another controversial article in 2018 about teen idol Yang Chaoyue (杨超越) that drew over 100,000 reads, and later faced accusations of fabrication along with a detailed analysis from Newslab.

Later, this same public account ran an article with the headline, “That 17 Year-Old Shanghai Youth Decided to Commit Suicide by Jumping off the Bridge” (那个17岁的上海少年决定跳桥自杀), in which it engaged in pure speculation about the facts behind the suicide in April of a teenager who jumped from the Lupu Bridge. The public account was subsequently shut down.

Searching job search websites we can see that this company behind “90s Tonight” proudly declaring recently that it is “starting up again as a completely new public account.” But while the account is a new one, it seems that the tactics and flavor are the same ones we are familiar with.

What should particularly distress us all is to see that this attitude of “greeting small misfortunes with small hymns, and treating major tragedies and great victories,” which was rejected by Chinese journalists 33 years ago, is now, in the traffic-oriented social media environment of the 21st century, being plucked off the garbage heap of history by this “90s Tonight” public account.

To the team behind “90s Tonight,” I wish to say: The professionalism with which journalists like Yang Lang, Lei Shumai, Li Weizhong, Ye Yan, Jia Yong, Wei Yanan and others worked to dig out the facts and get at the truth, exposing our maladies – therein lies the true awesomeness of what happened 33 years ago. And to employ cheap emotional language to cynically draw traffic is a most irresponsible exploitation of that tragedy.