Infectious diseases have no politics. In January 2020, through the course of the Wuhan people’s congress and the provincial people’s congress, no new coronavirus cases were reported in China. But the epidemic continued unabated – paying no heed to the political prerogatives of the Chinese Communist Party.

One of the medical facilities hardest hit by the coronavirus epidemic in Wuhan has been the Wuhan Central Hospital. On March 10, Caixin Media reported that the hospital, which has more than 4,000 employees, had at least 230 infections among its staff, the highest rate of infection among local hospitals. As of March 20, at least five of the hospital’s staff members had died of the coronavirus, including Li Wenliang (李文亮), Jiang Xueqing (江学庆), Mei Zhongming (梅仲明), Zhu Heping (朱和平) and Liu Li (刘励).

According to reports from Southern Weekly and China’s People magazine, on December 30, 2019, WeChat groups used by staff from various departments of Wuhan Central Hospital received the following information from the Wuhan City Health Commission: “We ask everyone please . . . . do not circulate at will to the outside notices and relevant information about a pneumonia of unclear origins . . . . otherwise the city health commission will subject them to severe investigation.”

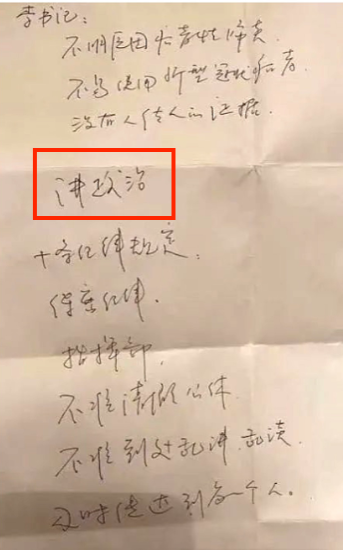

On January 3, Wuhan Central Hospital called an emergency meeting of hospital department heads, emphasizing that they must “speak politics, speak discipline and speak science” (讲政治, 讲纪律, 讲科学), that they must not manufacture rumors or spread rumors, and that departments must closely monitor their own staff to ensure that strict discipline is maintained. Medical personnel were explicitly instructed not to disclose confidential information in public, and not to discuss the disease through the use of text, images or other means that might leave evidence.

Since January, a digital copy of notes from that January 3 meeting, made by the now-deceased Jiang Xueqing, has appeared online, its authenticity verified by Chinese media. Jiang’s note include entries like: “10 discipline regulations”; “discipline in maintaining secrecy”; “no talking or discussion [without authorization.” And there is another phrase in Jiang’s notes – “speak politics.”

The unfortunate deaths of Li Wenliang, Jiang Xueqing and others owe in large part to “speaking politics.” In the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak, “speaking politics” meant the muzzling of medical professionals in Wuhan, and it meant that doctors and nurses were deprived of critical protections at a time of great urgency.

Behind the rapid rise of the novel coronavirus outbreak that would overwhelm Wuhan Central Hospital and other hospitals in the city is a decades-long lineage of “speaking politics” that goes to the heart of the political culture of the Chinese Communist Party. What, then, does it mean to “speak politics”?

“Speaking” + “Politics”

The simple verb “to speak” in this context has layered meanings. Aside from the basic sense of “talking” and “saying” it bears the sense of “paying attention” and “taking into account.” Perhaps a better translation might be “prioritizing.”

In the Analects, the teachings and thoughts of Confucius, there is the phrase “speaking credibility in relationships,” or jiǎng xìn xiū mù (讲信修睦), which essentially means paying attention to or prioritizing trust, and seeking harmony. In this context, “speaking” is both similar and different in meaning to the word “grab” or “grasp” (抓) as it appears in CCP discourse, which CMP has deal with previously. Both of these words are used frequently in documents from the CCP’s Central Committee, and hang ever on the lips of Party and government officials. But “speaking” in fact implies an active choice made on the psychological level (精神层面主动选择).

“Politics,” though a simple enough word, is far more complicated when we talk about “speaking politics.” The layers entail such meanings as “distinguishing between the enemy and ourselves” (分清敌我), or “rooting out the alien [or dissident]” (铲除异己). There is also a sense of “making use of style” (发扬风格) – another complicated phrase in an of itself – and sometimes of “stressing the equitable” (讲求公正) or “[abiding by] the rules of the game” (游戏规则).

“Politics” can have meanings that are abstract and distant, or close and concrete, and these meanings of course shift with the times.

Earlier on within the discourse of the Chinese Communist Party, “speaking politics” had the sense in most cases of propaganda or oratory – speaking (or teaching) political lessons, or propagating political and economic ideas. At the same time, it bore the sense of emphasizing or prioritizing politics, which of course mean the Party’s politics.

In 1942, Mao Zedong said in his Yan’an Talks on Arts and Literature: “There are two standards for criticism in arts and literature; one is the political standard, and the other is the artistic standard.” These speeches by Mao would become the fountainhead of the notion within the Chinese Communist Party that the arts and literature must “speak politics.”

In the first decade following its launch in 1946, three years before the establishment of the PRC, uses of “speaking politics” in the People’s Daily were largely didactic, having to do with political instruction. And there was a related sense of “speaking of principles” (讲道理), which essentially meant just behaving properly. On the front page of the May 14, 1948 edition of the People’s Daily, for example, there was an article with the headline: “Examining Left-Leaning Mistakes Within the Party: Striking Others is Wrong.” A special working team had held a meeting, said the report, to discuss whether it was permissible to hit others. One old man was quoted as saying: “I used to gamble all the time, and I suffered much punishment under the old government. . . . But the Eight Route Army [of the Chinese Communist Party] has come, and I don’t hit others, and I don’t cuss, and I speak politics. Who in our village will gamble now?”

By the 1950s, “speaking politics” had already come in the arena of economics and the military to stand in opposition to the notion of specializing in doing business or in certain technologies or abilities without the proper nucleus of political consciousness. This stemmed from Mao Zedong’s notion, found in texts such as his essay “Concerning Agricultural Questions,” that one should develop expertise only on the basis of a core of correct communist ideas. In the following passage, “white” signifies capitalist ideas and impulses, set against the red of communism:

Our cadres in all walks of life must strive to be proficient in technology and business, so that they can become well-versed in their areas, both red and professional. But the idea of first professionalizing and then becoming red [turning to communist politics] is like first being white and then turning red, and this idea is wrong. Because this kind of person in fact wishes to continue being white, and to say they will later turn red is just a ruse. Right now, there are certain cadres who are red but not truly red, their ideas those of the wealthy farmer class.

Other slogans that expressed this idea in the relationship between business and politics included: “political work is the lifeline of all economic work” (政治工作是一切经济工作的生命线) and “red and professional” (又红又专), the latter found in the passage above. In this oppositional relationship between “speaking politics” and “speaking business” (讲业务) there is an undercurrent of power struggle, and this power struggle was present in the arts, in the military and in the economy.

After the Lushan Conference was held in 1959, Lin Biao, who catered to Mao and emphasized the spiritual role of people, succeeded Peng Dehuai as Minister of Defense and was appointed vice chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC). The next year, the official commentary on National Day in the People’s Liberation Army Daily, the mouthpiece of the CMC, said: “The power of the material atomic bomb is great, but the power of the spiritual atomic bomb is greater still. This spiritual atomic bomb is the political consciousness and courage of the people.”

The term “spiritual atomic bomb” took the notion of “politics” and elevated it to the plane of strategic weaponry.

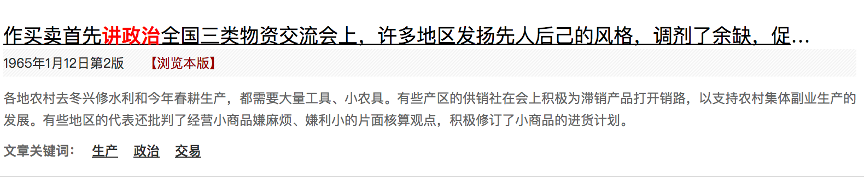

On January 12, 1965, a news story about “speaking politics” in the economic realm was published in the People’s Daily, and this was also the first time that “speaking politics” emerged in a headline in the newspaper. The headline, somewhat shortened here, was: “Speaking Politics Must Come First in Buying and Selling.”

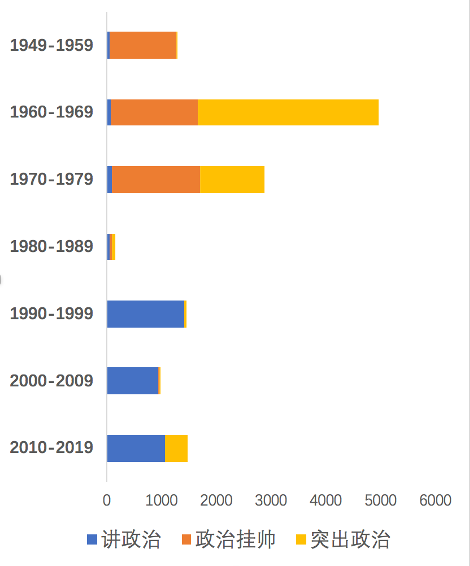

From the 1960s to the 1970s, the meaning of “speaking politics” can be equated with Mao Zedong Thought. During this period, which of course includes the Cultural Revolution, phrases like “giving prominence to politics” (突出政治) and “politics first” (政治第一) rise dramatically. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, these phrases came under sharp criticism, associated with Lin Biao and with the Gang of Four.

Deng Xiaoping’s priority was on business and the economy, and he famously said: “It does not matter whether a cat is black or white, but a cat that can catch mice is a good cat.” As Deng’s reform and opening policy defined a new direction for the country, Deng abandoned the Mao era slogan about “giving prominence to politics,” but he did not outright deny the important role of politics. In August 1986, Deng said during an inspection tour of the city of Tianjin: “If, alongside reform and modern science and technology, we speak politics, this will have the most power. At any time, we must speak politics.”

In the Jiang Era, “Speaking Politics” Becomes a Slogan

Consolidating power is a hard necessity for each leadership group. And after the criticizing of Lin Biao and the Gang of Four, it was no longer possible for Jiang to use Mao era slogans without incurring public resentment. In this context, the more direct phrase “speaking politics,” not over-burdened with Maoist associations, was chosen as a political slogan. The following graph show the slogans “speaking politics” (blue), “politics in command” (orange) and “giving prominence to politics” (yellow) in various eras.

On November 8, 1995, Jiang Zemin said during an inspection tour in Beijing: “When we conduct education for cadres, we must emphasize speaking study, speaking politics and speaking rightness. The entire country should act in this way, and the city of Beijing should serve a guiding role.” This speech initiated what at the time was referred to as the “three speaks education” (三讲教育). On November 25, two weeks later, “speaking politics” appeared in a headline in the People’s Daily:

This article in the People’s Daily offered an essential definition of the “three speaks, as follows:

Speaking politics includes political orientation (政治方向), political viewpoint (政治观点), political discipline (政治纪律), political discernment (政治鉴别力), political acumen (政治敏锐性) . . . . Leaders and cadres at all levels must remain sober and determined in their politics, maintaining unity in political and ideological terms with the Party of which Comrade Jiang Zemin is the core.

By this time, Deng Xiaoping was already old and frail, and in just over a year the old architect of the reform and opening policy would pass away. In order to consolidate his political power, Jiang Zemin defined and emphasized the notion of “speaking politics” as concession to his core leadership status, and obedience to his leadership.

Jiang Zemin emphasized again and again that news work (新闻工作), or journalism, must speak politics. In September 1996, Jiang made a visit to the People’s Daily, during which he said there was a need to “put the authority of leadership of news and public opinion in firmly in the hands of people who respect Marxism, respect the Party, and respect the people; news and public opinion units definitely must put adherence to the correct political orientation and adherence to correct guidance of public opinion in the primary position in all of their work.”

In the Xi Era, “Speaking Politics” is Renovated

In Xi Jinping’s so-called “New Era,” “speaking politics” has become more important than ever. In the seven years from 2013 to 2019, here is how the term “speaking politics” trended in the People’s Daily:

In January 2016, Xi Jinping said during the 6th full session of the 18th Central Discipline Inspection Commission: “We adhere to the [principle that] the Party must manage the Party, that the Party must be strictly governed. The investigation of the serious disciplinary and legal violations of Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai, Xu Caihou, Guo Boxiong, Ling Jihua, Su Rong and others have emphasized strict political discipline and the rules, creating an atmosphere of clear-cut politics and strict discipline.” From this point on, the phrase “speaking politics with a clear banner” would make frequent appearances in the Party-run media.

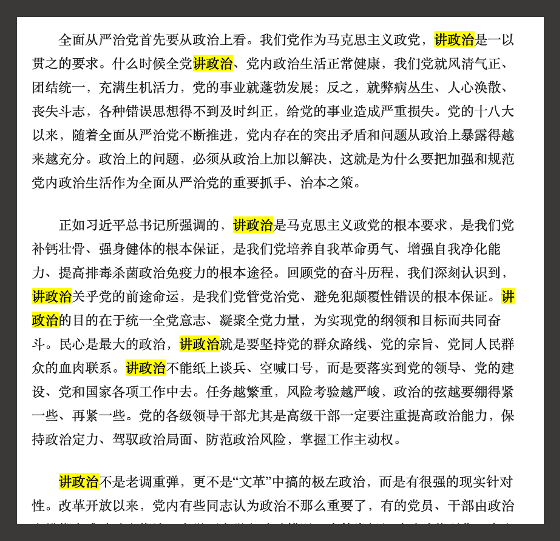

In October the same year, during the 6th Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the CCP, Xi Jinping’s status as “core” leader was established, and on February 14 of the following year, “speaking politics” appeared in a related headline in the People’s Daily: “[We] Must Speak Politics With a Clear Banner.”

The phrase “speaking politics appeared no less than 13 times in the commentary. “Speaking politics is a fundamental requirement of a Marxist political party, our calcium supplement,” the commentary said at one point, attributing the idea to Xi Jinping. “Speaking politics concerns the future and fate of the Party,” is said at another point. And: “Speaking politics is not the repetition of old tunes, nor is it the far-left politics in the ‘Cultural Revolution’; rather, it is directed and practical.”

In terms of consolidation of power, the “New Era” has been a robust period of new slogan manufacturing, all lending fresh layers of discourse to the notion of “speaking politics.” Prominent among these slogans have been the so-called “Four Consciousnesses”—“political consciousness” (政治意识), “consciousness of the overall situation” (大局意识), “consciousness of the core” (核心意识) and “compliance consciousness” (看齐意识)—and the “two protections” (protection of the core leadership status of Xi Jinping, and of the centralized leadership of the Chinese Communist Party).

In his comprehensive review of Chinese political discourse in 2019, Qian Gang looked at how local Party media and military media (军报) used the “four consciousnesses “ and the “two protections,” signaling their loyalty to Xi Jinping and the Party. For example, on November 22, 2019, the local Wulong News in Chongqing used the phrase “respecting the core, protecting the core, complying with the core, and following the core” (忠诚核心、维护核心、看齐核心、追随核心). Jiangxi province’s official Gan’nan Daily wrote on the same day of “protecting the core, supporting the core, and following the core both in our hearts and in our outward actions” (将维护核心、拥戴核心、追随核心内化于心、外化于行).

At the 4th Plenum in October 2019, Politburo Member Ding Xuexiang wrote in the People’s Daily:

The ‘Two Protections’ have a clear meaning and demand, to protect the core status of General Secretary Xi Jinping, and the object is General Secretary Xi Jinping and no other person; to protect the centralized and unified authority of the Central Committee of the CCP, the object being the Party’s Central Committee and no other organization. The authority of the CCP Central Committee determines the authority of Party organizations at all levels, and the authority of Party organizations at all levels comes from the authority of the CCP Central Committee. The ‘Two Protections’ can neither be applied layer by layer nor extended at will.

This passage makes it very explicit what is meant by “speaking politics.” As Ding Xuexiang lays out the essentials, there can be no doubt whatsoever.

As the Epidemic Raged, What Did “Speaking Politics” Mean?

2020 was meant to be China’s year of victory in its war against poverty and the building of a “moderately well-off society.” Early on in the year, before the coronavirus epidemic was pushed into the spotlight, it was clear that this supposed victory was the centerpiece of the Party’s propaganda strategy.

In Wuhan, which would soon become the epicenter of the epidemic, the Changjiang Daily, the official newspaper of the municipal Party committee, was not to be outdone in its declaration of victory in the war on poverty. A front-page article in the paper declared that Wuhan would become “China’s Fifth City” after Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

In early 2020, as the coronavirus outbreak spread, what took precedence in the politics of Wuhan and Hubei province? The priorities were the celebration of the annual Spring Festival, the holding of the city and provincial sessions of the people’s congress and political consultative conference, the touting of the Party’s victories in fighting poverty, and the “Two Protections.” All of these were ultimately about the “Four Consciousnesses,” and as such were about the core status of Xi Jinping and the leadership of the Central Committee.

On January 10, the Changjiang Daily, Wuhan’s official Party newspaper, published the speech given by the city’s top leader, Ma Guoqiang (马国强) to the local people’s congress. In his speech, Ma emphasized the need to “speak politics with a clear banner.” Nowhere in his speech did Ma mention the coronavirus outbreak, which at that point was still not being dealt with openly in China.

On February 15, not long after Ma Guoqiang’s replacement as Wuhan’s top leader, the Changjiang Daily ran a report about a study session led by the city’s new top leader, Wang Zhonglin, that again emphasized “speaking politics,” though by his point the response to the coronavirus epidemic was an open agenda, having redirected the focus of news and propaganda efforts since Xi Jinping’s first public comment on the epidemic on January 20. The Changjiang Daily piece read: “Under the provincial Party leadership of session leader Comrade Ying Yong, and under the guidance of session leader Comrade Wang Zhonglin of the city’s Party Committee, [the study session] spoke politics, attended to the general situation and abided by the rules.”

“Speaking politics” has had varying meanings at different times in China’s history. In the early days of 2020, as the virus silently spread, “speaking politics” meant “not talking haphazardly” (不准到处乱讲). Once the response effort had actually begun after January 20, “speaking politics” meant shutting down cities, closing off roads and building emergency field hospitals like Huoshenshan. At the most challenging point of the response effort, “speaking politics” meant carrying out stability preservation in restive residential districts – like the one in Wuhan that heckled Vice-Premier Sun Chunlan during her inspection tour on March 6. In the most recent stage of China’s response, “speaking politics” is about being tough on restricting international arrivals who might reintroduce the virus, and about getting economic activity going again.

“Speaking politics” has often meant rushing into disaster – and many, like Doctor Li Wenliang (李文亮) and Doctor Jiang Xueqing (江学庆), have paid with their lives for its expedient focus on the shifting interests of the CCP leadership. So long as China fails to face the painful lessons of “speaking politics” and its privilege over humanity and conscience, its flag will continue to fly high, drawing attention away from real threats and dangers.