A troupe of Red Guards dances the “Loyalty Dance” in 1968. Image from Wikimedia Commons in the public domain.

The “loyalty dance,” or zhongziwu (忠字舞), was a collective dance that became prevalent during the Cultural Revolution, at a time when Mao Zedong and his image reigned supreme over all aspects of life in China. The dancers, grasping their copies of the “little red book,” Quotations From Chairman Mao, would dance, leap and shout to the impassioned ring of the music – all to express their boundless loyalty to the Chairman.

One slogan older Chinese may remember from that time, related to the loyalty dance, is the “Three Loyalties” (三忠于): loyalty to Chairman Mao; loyalty to Mao Zedong Thought; loyalty to Chairman Mao’s revolutionary line. It is tempting to think of the loyalty dance and the “Three Loyalties” as relics of China’s political past. But in fact, there are unmistakable echoes in the present.

How, in Xi Jinping’s so-called “New Era,” does one dance the loyalty dance?

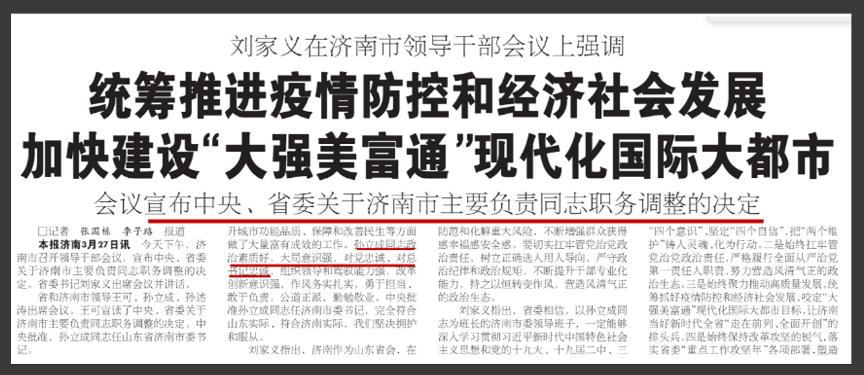

Last month, CMP wrote about how the top leader in the city of Wuhan stirred up trouble as he tried to signal his “gratitude” toward Xi Jinping, suggesting that the people of Wuhan, then still in recovering from the coronavirus epidemic, should undergo “gratitude education.” This leader, Wang Zhonglin, was previously the top Party official in the city of Jinan in Shandong province, and when official media recently reported the news of Wang’s replacement taking up his post, certain words caught my eye.

As Shandong’s provincial Party secretary praised Wang Zhonglin’s replacement in Jinan, we had a pair of loyalties: “He is loyal to the Party,” said Shangdong Secretary Liu Jiayi (刘家义), “and loyal to the General Secretary.”

When exactly did the music start in this present-day loyalty dance?

After Xi Jinping came to power, the word “loyalty” was, at least on the surface, applied to the Party and not to any individual. Xi said during his first five-year term: “Absolute loyalty to the party lies in the word ‘absolute’, which is the only, thorough, unconditional, uncontaminated, and undiluted loyalty.” Xi is of course unlikely to talk himself of the need to be loyal to himself; signaling the need for such expressions of loyalty is something that can be left to others at the top of the CCP.

But as Xi consolidated power at the top and emphasized the need for loyalty to the Party, Li Hongzhong (李鸿忠), the top leader in the municipality of Tianjin, offered what could be considered the most innovative (and perhaps humorous) rendition of the loyalty equation: “If loyalty is not absolute, then it is absolutely not loyalty,” he said.

In October 2016, as the Party held its 6th Plenum, Xi Jinping’s status as the “core,” or hexin (核心) became definitive, an unmistakable sign of his solidified position. In fact, the writing had been on the wall through much of 2016, and local leaders correspondingly signalled their loyalty. In February 2016, Chen Quanguo (陈全国), then Party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region, led the way, introducing the phrase “firmly protecting, supporting and remaining loyal to the core that is General Secretary Xi Jinping.”

After the 6th Plenum a slew of different phrases denoting loyalty to Xi cropped up in the Party media. These included:

“Trusting the core in thought, loyal to the core politically, loving the core emotionally, and maintaining the core in action.” – vice-governor of Qinghai province Zhang Guangrong (张光荣), appearing in the Qinghai Daily on November 24, 2016

“Clean, and loyal to General Secretary Xi Jinping.” – Pan Wujun (潘武俊), political commissar of the Ningxia Military Region, appearing in Ningxia Daily on January 11, 2017

“To General Secretary Xi Jinping, absolute loyalty and pure loyalty.” – Jilin Party Secretary Bayanqolu, appearing in Jilin Daily on January 11, 2017

“Loyalty to the Party, loyalty to the General Secretary.” – spoken first by a forestry official in Jilin province, appearing in the Yichun Daily on December 22, 2017

Liu Jiayi’s use of the “two loyalties” (两个忠诚) as he introduced the new leader in Jinan is only the latest example. But so far, the “two loyalties” and related phrases have not yet appeared in the People’s Daily. The loyalty dance is not yet a national dance, and whether it will become so remains to be seen.

Generally speaking, the Chinese Communist Party has three attitudes toward political slogans and key phrases. The first is to welcome and promote slogans, encouraging their use, which applies to mainstream CCP phrases like “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” the “two protections,” or “Belt and Road.” The second attitude is to prevent or restrict the use of certain phrases, particularly those regarded as sensitive, including “judicial independence,” “freedom of speech,” and so on. These are often blocked outright, prohibited from appearing in the media or online.

Finally, there are those terms on which the Party’s attitude might be characterized as ambiguous. These are words or phrases that can, depending on context, be regarded as either sensitive or non-sensitive. In the Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao eras, for example, terms like “constitutionalism” and “civil society” were not necessarily regarded as negative, and could be found in the media (particularly the commercial media), but these terms were never used by top leaders, and they could seldom if ever be found in the flagship People’s Daily. Since 2013, these terms have been more explicitly designated as unacceptable, and have virtually disappeared from use in the media.

At the other end of the ambiguity spectrum are terms of praise or positivity that run the danger of being unseemly owing to historical associations or the potential for blowback. One of the most classic recent examples might be “great leader Xi Jinping” (伟大领袖习近平), a phrase that appeared in at least one local newspaper but was subsequently removed.

The phrase “loyalty to the Party, loyalty to the General Secretary” can be regarded as an ambiguous phrase under the current political environment, meaning that, though positive from the standpoint of CCP leaders, it does not appear in the People’s Daily or high-level speeches or other documents. But local officials know, at the same time, that there is little or no risk for them in shouting the phrase to the heavens, which might actually put them in good favour with senior officials.

Liu Jiayi, the Party secretary of Shandong province, knows this principle only too well, which is no doubt why he chose to express his loyalty to Xi Jinping and the CCP while inviting a new city leader to his post.

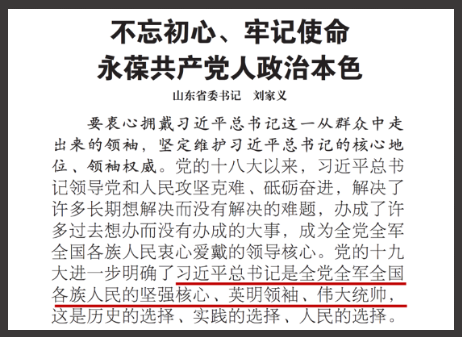

Nor is this Liu’s first time going beyond the call of duty to shower praise on Xi Jinping. Shortly after the 19th National Congress in October 2017, the CCP issued a notice standardizing the discourse of praise for Xi, okaying the use of “a leader cherished by the whole Party, loved and respected by the people, and worthy of the title” (全党拥护, 人民爱戴, 当之无愧). But even this moderated phrase, designed to tone down the parade of unctuous accolades for Xi, was soon withdrawn amid concerns of the emergence of a personality cult around the general secretary.

In Shandong, Liu Jiayi was determined to keep the adulation going. He spoke of Xi Jinping as “the staunch core, wise leader and great commander” (坚强核心, 英明领袖, 伟大统帅), the last of this trinity redolent of the title “commander” given in the pre-reform era to Mao Zedong.

So far, Liu Jiayi is in a league of his own when it comes to dancing the loyalty dance. Since January 2020, the country has focused on fighting the coronavirus. When we search newspapers over the past few months, we find Liu is the only leader in the country openly signalling loyalty to Xi Jinping. Liu’s remarks appeared only in Dazhong Daily, Shandong’s official Party mouthpiece, the newspaper directly under Secretary Liu’s thumb, and a few other local Party papers – though they were included in several online sources (including on the People’s Daily news app, shown below).

These days, there are no signs anywhere else in China’s official Party media of phrases of obeisance such as “loyal to General Secretary Xi” (对习总书记忠诚), “loyal to General Secretary Xi Jinping” (对习近平总书记忠诚), “loyal to the General Secretary” (忠诚于总书记), “treating General Secretary Xi with loyalty” (忠诚于习总书记) and so on.

In this “New Era,” will the loyalty dance become as popular as it was during the Cultural Revolution? As we observe Chinese politics, this is another interesting question to bear in mind, looking for signs of the dance in the ever-shifting discourse of the Party.