China Newspeak

Western Surveys for Chinese Democracy

In the weeks ahead of December’s Summit for Democracy, which US President Joe Biden called a “push back on authoritarianism,” China and Russia bristled at their exclusion and stood shoulder-to-shoulder in condemnation. In a joint article ahead of the summit, Chinese and Russian envoys to the US called the event a “product of Cold War thinking.” Chinese diplomats and official media pushed back against Biden’s portrait of a broader struggle between autocracy and democracy by insisting that China’s system is not just democratic, but more democratic than political systems in the West.

Three months after the US-led summit, as the eyes of the world turn to Russia’s invasion of a sovereign and democratic Ukraine, China’s campaign to promote its own form of democracy remains strong. The global re-framing of democracy is clearly a longer-term strategy for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which claims “whole-process democracy” (全过程民主) as a democratic system distinct from “that in the West.” And in China’s recent discourse on democracy, loudly proclaimed in the state-run media, one concept emerges again and again – that a government’s “level of trust,” or xinrendu (信任度), is the fairest measure of democratic practice.

During a press conference on the sidelines of the National People’s Congress this week, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi (王毅), was asked by the Global Times newspaper what he felt about a recent US announcement that it would host a second, offline Summit for Democracy. Wang responded by praising China’s “whole-process democracy,” and referring the paper, a spin-off of the CCP’s official People’s Daily, to global surveys as proof:

China’s full process people’s democracy is a broad, true and working democracy wholeheartedly embraced and supported by the Chinese people. In January, Edelman, the world’s largest public relations consultancy, released its global Trust Barometer report, stating that trust in the government in China reached 91 percent in 2021, the highest in the world and a ten-year high. Similar polls have been produced by Harvard University in the United States for a number of years. These polls are third-party polls, from which we can see that the world recognizes China’s democracy and we are more confident in our own path.

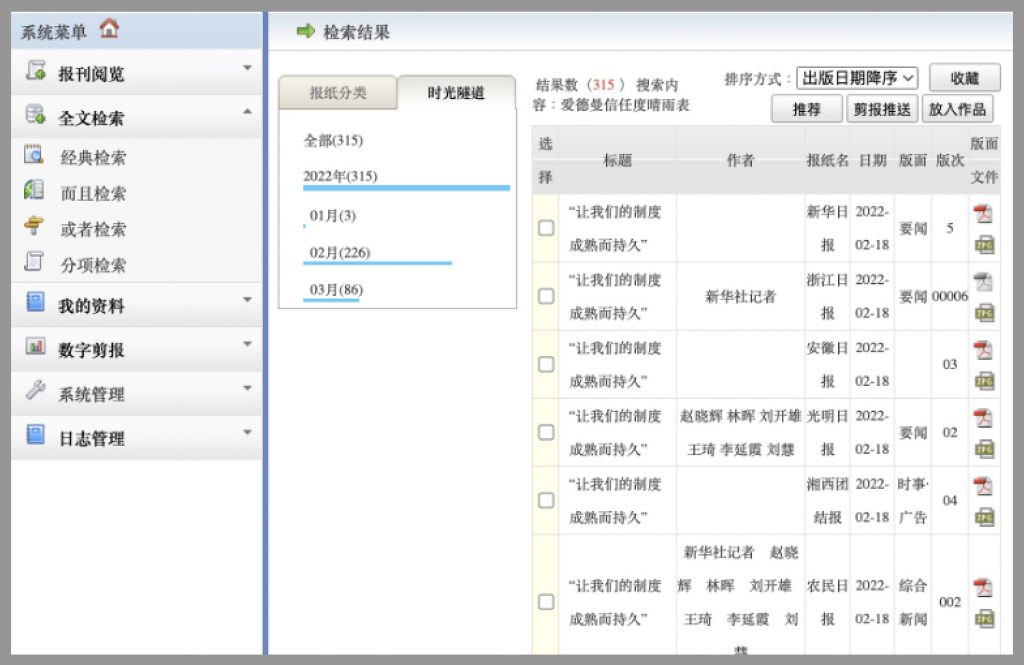

These numbers could not have been news to the Global Times. Since Edelman Intelligence released its latest report, the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, on January 18, it has been mentioned in 315 articles in media across China.

In February alone, 226 news articles were published in the Chinese media citing the Edelman survey. Most of these articles, however, were syndicated from an official new release from Xinhua News Agency called, “Making Our System Mature and Long-Lasting” (让我们的制度成熟而持久). The news release, which was likely published in provincial and city-level CCP newspapers under express instructions from propaganda authorities, said that the Chinese system had saved millions of lives during the pandemic, and that “China’s rule” (中国之治) had stood in stark contrast to the “chaos of the West” (西方之乱). Such enviable results had been possible, said the article, only because China had “actively developed whole-process people’s democracy, effectively ensuring that the people are the masters.”

Then, right on cue, came mention of the Edelman results: “In January 2022, Edelman, a leading global public relations consultancy, released its Edelman Trust Barometer, which shows that trust in the government in China reached 91 percent in 2021, up 9 percentage points from the previous year, making it the world’s number one.”

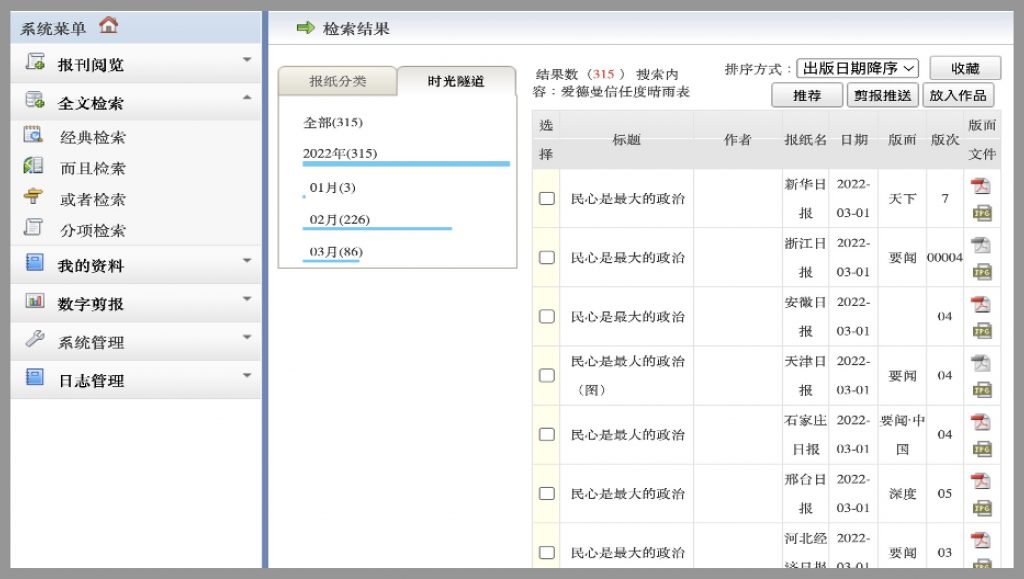

So far this march, the Edelman Trust Barometer has been mentioned in 86 articles, according to the Qianfang database. Once again, the vast majority of these have stemmed from a single Xinhua release, this time called, “Popular Sentiment is the Greatest Politics: Seeing Through to the Chinese Secret Behind [Government] Trust and Satisfaction” (民心是最大的政治—透视信任度满意度背后的中国密码). Apart from the Edelman statistics, which were mentioned right from the start of the article, it cited results from Harvard University’s Kennedy School (the same referenced by Wang Yi this week) showing that government satisfaction in China has remained above 90 percent for many years.

The Xinhua article said that the popular sentiment, or minxin (民心), was at the heart of Chinese democracy. And it emphasized that Xi Jinping cared deeply about the “political accounts” people kept in their hearts. The context of the article made clear, however, that these “political accounts” were really about basic results on economic development and livelihood issues, and not about the political process itself. China’s democracy was shown not in active citizen participation, regular free and fair elections, political tolerance, transparency or any number of generally recognized principles of democratic governance. Rather, it was demonstrated by declared results – specifically, the CCP’s claimed progress on poverty alleviation.

It is crucial to understand, as the CCP emphasizes the results of its governance, that the entire CCP-led system works not just to mobilize action on policy campaigns but to publicize the success of those campaigns irrespective of the results. Propaganda often precedes the policy outcome, as CMP has shown in past research and monitoring. Results, moreover, are often quite explicitly about political results and leadership prestige over the public welfare.

The article made a big deal of Xi Jinping’s visit in December 2012, early in his first term as general secretary, to Fuping (阜平) county in Hebei province, one of the country’s poorest areas. There, we are told, he “inspected real poverty” (看真贫), “took the measure of public sentiment, listened to the voices of the people and gathered public opinion (察民情, 听民声, 纳民意).

How can one central-level leader making a visit to a single county be taken seriously as proof of “democracy”? The answer, for Xinhua at least, is in the results of China’s campaign to eradicate poverty, which the article describes in broad-brush fashion: “By the end of 2020, all 832 poor counties in China, including Fuping, had said goodbye to absolute poverty. The following year, a moderately prosperous society was fully built in China, and the Chinese people started a new journey to build a comprehensive socialist modern country.”

The argument in this and other pieces citing the Edelmen report is simple. All work backward from the question of trust in the government to determine whether a political system is democratic. If there are high levels of trust, this has to mean that the government achieved results; and if the government achieved results, this means that the voice of the people was heard. “In today’s world, mankind faces many common challenges. From the pandemic ravaging the world to climate change issues impacting livelihoods; from the sluggish recovery of the world economy, to employment issues affecting people’s livelihoods,” the second Xinhua release concluded. “All of these are ‘major tests’ for governance in each country. Whoever can better solve these problems will gain the trust of the people.

Trust and Democracy

Western surveys on government trust raise many questions as they are applied to broader questions of democracy, particularly in closed authoritarian systems like China’s. One of the first questions many will have concerns the reliability of survey research conducted in China, where opinion polling can be subject to strict government control.

A paper in the China Quarterly nearly 20 years ago, in the era before the internet, underscored the “impossible and impractical” situation in China in terms of obtaining a nationwide probability sample. It noted, for example, that interviews, “however skillfully and cleverly designed, must practically always be conducted with Chinese in localities selected not according to any principle of random selection but chosen partly for the convenience and always subject to the approval of the Communist Party.”

Certainly, as even the scholars behind the Harvard study cited recently by the Chinese media note, “gathering reliable, long-term opinion survey data from across the country is a real obstacle.” In the case of the Edelman survey, data was gathered online, and experts have raised basic concerns in the past about the sampling involved. As Petko Kalev of Australia’s La Trobe University noted after the release of Edelman’s 2021 survey: “I have huge doubts, and hence I am quite concerned that sampling for example China, with about 1150 respondents from a total population of about 1.412 billion, is not comparable with the 1150 respondents drawn from the Irish population of 5.17 million.”

But the unreliability of Chinese surveys, insofar as they reflect the real views of ordinary Chinese, can also be overemphasized. It is not necessarily true that the views held by Chinese citizens are effectively shaped by the CCP. Nor is it necessarily true that Chinese feel too fearful in any case to share how they really feel.

A more pertinent question may concern not the reliability of data about trust, but the relevance of such data as a democratic metric at all. As political scientist Mark E. Warren has written, distrust may in fact be an important aspect of democratic cultures, so that democracy “includes a healthy distrust of the interests of others, especially the powerful.” Democracies, Warren suggests, “institutionalize distrust” by empowering populations to scrutinize and criticize those “empowered with the public trust.”

Measuring Up

Whatever the case, the positive correlation between government trust and democracy has become a matter of conviction for the Chinese leadership, and a core aspect of the campaign in state media to promote China as a democratic leader. Ultimately, the argument boils down to the assertion that the key to democracy lies not in the process at all, but rather in results-based concepts of responsiveness.

A more pertinent question may concern not the reliability of data about trust, but the relevance of such data as a democratic metric at all.

As this logic was mirrored in May last year in HK01, a pro-Beijing Hong Kong news outlet, it became even plainer. “We can even say that while democratic elections in the West allow for the constant changing of rulers, if there is no improvement in the governance of the country, if social problems are not resolved – or if there is a crisis like COVID-19 and chaos ensues – then the people will not be satisfied or trust the government, regardless of how it is replaced,” the outlet wrote. “Whether or not the government has the trust and satisfaction of the people is ultimately not a matter of how it was created, but whether or not it is able to respond to the urgency of the people, which is perhaps the true meaning of democracy.”

As Hong Kong now struggles, just eight months later, with chaos and panic stemming from the mishandling of an outbreak it has been told by Beijing to curb at all costs, those words are newly significant.