Close-up of chips and slots on a computer motherboard. Image by Nenad Stojkovic available at Flickr.com under CC license.

When China Computerworld (计算机世界) was launched in 1980, the magazine was one of the most positive and exciting media developments China had experienced in a generation. The country’s first information technology (IT) related publication, its success was premised, as its publisher would later say, on “providing readers with practical information.”

It was a simple positioning – this prioritizing of the reader. But against the backdrop of two decades of Maoist sloganeering in the media, it was also a revolutionary shift. Chinese media were slowly entering a new period of experimentation and openness to the world in the early 1980s, and China Computerworld was at the forefront of these changes, an early trailblazer of a media commercialization trend that would not gain full momentum for another 10 years.

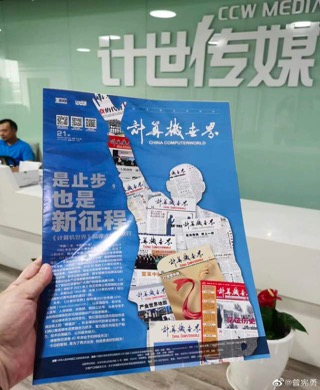

So when this pioneer of media commercialization in China’s reform period announced in April this year that it would be formally closing up shop, the news bookended four decades of print media development. It was the fizzling out of a magazine that had once played an instrumental role in the growth of China’s IT industry – spearheading a trend that in decades to come would be its undoing, as new digital media eclipsed traditional outlets.

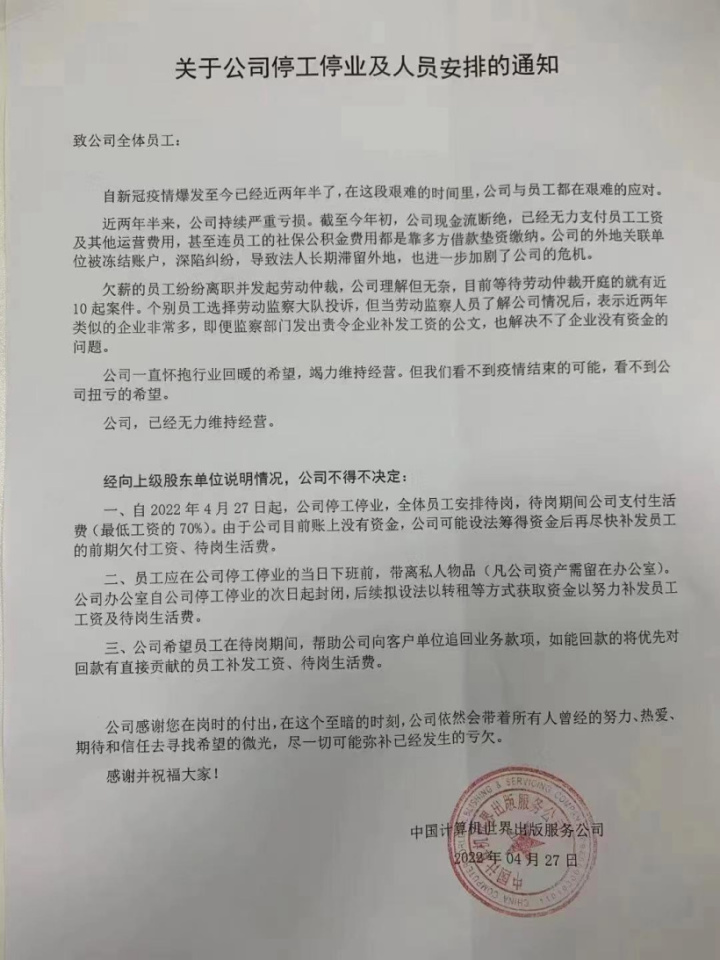

In a notice dated April 27, 2022, China Computerworld announced that it would immediately cease operations and enter into labor arbitration with staff members who claimed wages in arrears. The notice began by noting the extreme difficulties that had come in the past two and half years as a result of the pandemic, which had resulted in “continuous and serious losses.”

A Mass Media Extinction

But the uncomfortable fact was the China Computerworld was joining the long ranks of media that had either been folded into new digital operations – as Shanghai’s Oriental Morning Post had been in 2016 with the founding of a fully digital venture ironically called The Paper in English – or had failed to make the transition to digital.

January 2016 had brought the closure of the Morning Express (今日早报), a commercial paper under the official Zhejiang Daily, of Hangzhou’s Metropolitan Weekly (都市周报), of the Jiujiang Morning Post (九江晨报) and the Daily Commercial News (天天商报). The next year brought the closure of the Beijing Times (京华时报) and the Oriental Morning Post (东方早报), the latter a commercial paper remembered for having broken news of the poisoned milk scandal after the 2008 Beijing Olympics. In 2018 there were countless closures, including of the Beijing Star Daily (北京娱乐信报), and of local commercial papers like the Xiangtan Evening News (湘潭晚报) in Hunan province. In 2019, the Beijing Morning Post (北京晨报), the Heilongjiang Morning Post (黑龙江晨报), Dalian’s New Commercial Post (新商报), and many others at the city and prefectural levels.

The global pandemic may have been the last chapter for some. But a mass extinction of print publications in China was already well underway by the time the virus was discovered in Wuhan in late 2019. Nearly all have been commercial newspapers, many launched in the late 1990s and 2000s as profitable spin-offs of Party-run newspapers across the country, at a time when print advertising was booming. By the 2010s, that market was already cratering, impacted by the rise of new digital platforms like Tencent’s WeChat.

In the 2020s, their former Party sponsors plod on, still supported with government funds, and still needed to conduct essential propaganda and “public opinion work.” But these commercial ventures, which in their own ways all took cues from the example first set by China Computerworld, are now confined to a fossil past in university libraries and digital archives.

The global pandemic may have been the last chapter for some. But a mass extinction of print publications in China was already well underway by the time the virus was discovered in Wuhan in late 2019.

Rare Species: The Sino-Foreign Media Joint Venture

Launched as a joint venture between the now dissolved Ministry of the Electronics Industry and the US-based International Data Group (IDG), China Computerworld was also the first foreign-invested media venture in China – a rarity looking back on more than four decades during which foreign dreams of media access to the country have been elusive.

During a trip to China in March 1980, IDG founder and chairman Patrick McGovern entered into discussions with the Fourth Ministry of the Machinery Industry, which would eventually be reorganized as the Ministry of the Electronics Industry, about the possibility of launching a Chinese-language edition of his IT related magazine. Computerworld‘s publications around the world were at that time all owned or controlled by IDG. But McGovern’s efforts to push for the same arrangement in China were quickly rebuffed. China, which had just embarked on its reform and opening path, refused to allow more than 50 percent foreign ownership in a joint venture. The two sides eventually agreed that China would hold 51 percent, the remaining 49 percent to be held by IDG.

Then, as now, media were a point of sensitivity for China’s leadership. The sense from the top, however, was the Computerworld would deal primarily with IT issues, and would eschew politics. Moreover, the information it would share with readers would be essential to the introduction of advanced computer technology from the West. IDG’s investment was greenlighted, and by the fall of 1980 China Computerworld had been approved by the government, becoming the country’s first industry-focused publication and its first foreign investment in the media. When China’s government later prohibited foreign investment in the news media, the magazine became the only official Sino-US joint-venture magazine – a historical first, and last.

Through the 1980s the magazine was an example to follow for journalists and publishers who hoped to break new ground. Even as the country’s international relations soured and its media grew bitter and insular in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing, the magazine offered a crucial link with the outside. In April 1992, just weeks after Deng Xiaoping’s “southern tour,” which was to reinvigorate economic reforms (and bring a new commercial media renaissance), the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper noted China Computerworld as a bright spot of global engagement. The magazine’s “timely tracking of international [developments in] computer and high-tech,” the paper said, had made it “the most authoritative professional publication in our country’s computer industry.”

Profit and Professionalism

China Computerworld was sometimes also called the first “thick publication” (厚报) in the history of the People’s Republic of China. Unlike the Party-run dailies and weeklies of the 1980s (and even their commercial spin-offs of the 1990s), which might have anywhere from eight to 16 pages, the IT magazine could have at times up to 300 pages in a single issue, stuffed full not just of content but of advertising.

Through the 1980s the magazine was an example to follow for journalists and publishers who hoped to break new ground.

But China Computerworld could also get tough with the IT companies about which it reported, and its advertisers – even the powerful ones – were not always spared.

In January 2000, the magazine ran an eight-page story about Legend Computer, later to be renamed Lenovo, that detailed the early rift in the 1980s between computer engineer Ni Guangnan (倪光南) and Liu Chuanzhi (柳传志), then an official at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Called “The Painful Fracture” (痛苦的裂变), the lengthy investigative report revealed that Ni was in fact the founder of Legend, where Liu Chuanzhi had served as CEO (and identified himself as founder) since 1984. The China Computerworld report so infuriated Liu that Legend pulled nearly 20 million yuan in advertising – at the time the largest case of advertising withdrawn in China for critical reporting.

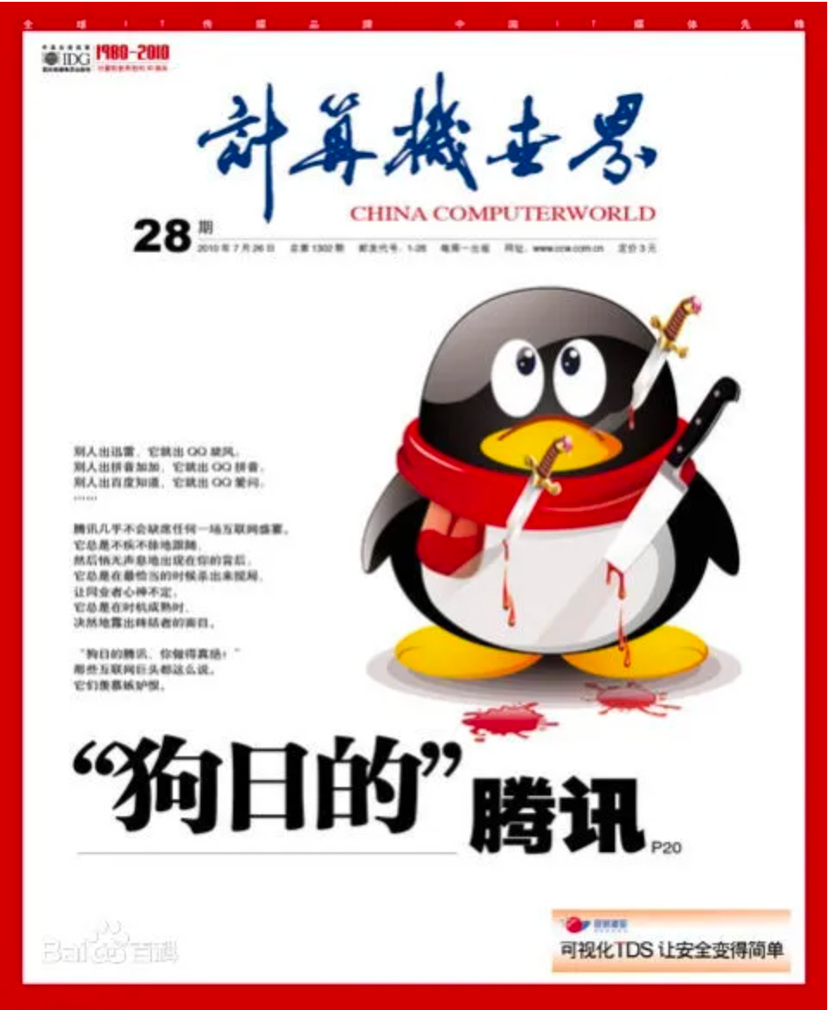

Ten years and a generation of technology later, the magazine infuriated another tech giant with a cover story called “Damned Tencent” (狗日的腾讯), which described Pony Ma’s Tencent as the internet’s public enemy, fueling bitter feuding within the industry and resorting to monopoly behavior. The feature story was brimful of bitter accusations from Tencent competitors. China Computerworld’s cover image was the iconic penguin symbolizing Tencent’s QQ service, but with three knives stabbing his plump cartoon body, drawing drops of bright red blood.

“This is Tencent, China’s top and the world’s number three internet company, a rare global full-service Internet company that does everything from instant messaging, portals, games, e-commerce, search and more. It is always quietly making preparations and appearing behind your back, popping out to stir up trouble at moments of opportunity, leaving its peers unsettled,” the story read.

The magazine then went for the jugular: “When the time is ripe, [Tencent] will ruthlessly seize its piece of the market, sometimes even acting like the Terminator to dominate the entire market.”

Tencent was understandably upset by the July 2010 cover story. But it received widespread support on the internet, and prompted China Computerworld to change its profile picture on Weibo to the same image of the bloody penguin. It was unusual feistiness for a publication majority owned by that time by the government’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). But the magazine’s large base of readership with the internet industry, and among scholars and businesspeople, not to mention its enviable advertising revenue, meant that had more latitude in reporting about technology matters in China.

Falling Behind the Trends

Ultimately, though, it was Tencent that had the last laugh. Perhaps more than any other competitor in the past 10 years, the Chinese tech giant transformed the media landscape in ways that China Computerworld failed to anticipate.

From 2008 onwards, the development of new forms of internet communication, including Tencent’s powerful WeChat, launched in January 2011, would leave traditional media outlets in the dust. China Computerworld made a number of halting attempts at digital transformation, but these were ultimately unsuccessful. Wrote Shanghai’s Jiemian News, in what might be an apt epitaph for the magazine: “China Computerworld nurtured the growth of China’s IT industry, but its failure in the face of several internet transformations ultimately brought the publication down in front of its rivals.”

In recent weeks, many internet users, particularly those in the IT industry, have expressed their sadness at seeing the once-celebrated magazine suffer the same fate as so many print publications from the golden era of the commercial press in China.

A few have blamed the closure of local newsstands in recent years for circulation drops that have hit print media hard. “The wave of newsstand removals in the past few years was a devastating blow to these paper magazines,” read one recent comment under a months-old story on newsstand closures by the online publishing platform 36kr. “I would always grab a copy of China Computerworld from the newsstands after work, but now I don’t even know where I can find [such a newsstand] anymore.”

Others were more resigned to the irreversible trends transforming the media. “There is nothing we can do about it,” one user commented under a story at Sina.com on the closure of China Computerworld. “The era of print media has passed, and all of them will fall under the onslaught of online media.”

Stella Chen contributed research for this story.

David Bandurski