Electrical engineering students at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China (UNNC) campus. Image by PengXH available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

In the midst of more pressing stories, including a wave of Covid lockdowns and an earthquake in Sichuan, a government notice issued over the weekend on “the popularization of science,” or kepu (科普), may not command attention. But it is the latest sign of how politics and ideology have in recent years crept back into the heart of all endeavors in China.

Released by the general offices of the CCP Central Committee and the State Council, the notice encourages the spread of knowledge about science and technology, both in the government and in the wider population, in the interest of establishing a firm foundation for innovation and development. It speaks of “advocating the spirit of science,” and “promoting scientific approaches to activities,” and it signals concern over the fact that “the supply of high-quality science products and services remains insufficient.”

But science quickly moves aside for politics.

Point one in “General Requirements” opens with a clear declaration that the guiding ideology for science popularization is the top leader’s banner phrase, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想). The second point then addresses concrete “work demands”:

[Work must] adhere to the leadership of the Party, implementing the leadership of the Party through the whole process of science popularization, highlighting the political properties of science popularization, strengthening the leadership of values, practicing socialist core values, and vigorously promoting the spirit of science and the spirit of the scientist.

This talk of the “political properties” (政治属性) of science popularization is a salient reminder that through much of its history, particularly in the pre-reform period, the CCP has regarded science on the one hand as both a crucial contributor to national development, supporting economic growth and self-reliance, and on the other as intimately inter braided with political claims to truth as a source of political power.

Even as Xi Jinping has re-emphasized the need for self-reliance in science and technology, and has made innovation a key buzzword, his rule has reconsolidated Party control over the sciences. In science education, as in other fields, “ideological and political education,” or sixiang zhengzhi jiaoyu (思想政治教育) — sizheng (思政) for short — has been redoubled.

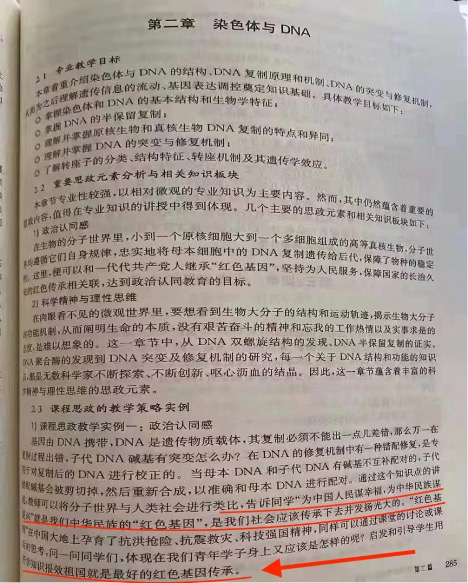

Biology textbooks in China now explicitly link the study of the subject to patriotic goals and love of the CCP. One textbook encourages an attitude of thankfulness and indebtedness, concluding: “Inspiring and leading students to use scientific knowledge to repay the kindness of the mother country is the best means of passing on red genes.”

The phrase “red genes,” or hongse jiyin (红色基因), refers to the revolutionary spirit and history of the CCP as a form of political and cultural inheritance, the celebration of which is a means of consolidating the Party’s position within the national identity and thereby constructing the legitimacy of the regime.

Point 25 of the notice released on September 4 is crystal clear about the implications of science popularization for public opinion, the control of which the CCP regards as essential to maintaining political stability. The language emphasizes the need to “strengthen public opinion channeling in the field of science popularization,” “adhering to the correct political positions, and strengthening the construction and supervision of public opinion positions in science popularization.”