When Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was mentioned a single time in the flagship newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party back in March, this minuscule event seemed momentous. Up to that point, through 13 dreadful months of a war that had dominated world affairs and claimed the lives of close to 20,000 civilians in Ukraine, the People’s Daily had mentioned Zelensky just once.

Let the absurdity of that fact sink in for a moment.

The People’s Daily is meant to coalesce and communicate the power and vision of the CCP leadership under Xi Jinping, to signal its position on domestic and foreign affairs. It is the authoritative reference book to which observers everywhere turn for a glimpse of what China’s authoritarian strongman and his acolytes, who govern a population of 1.3 billion, are thinking. And yet, for nine months last year, as missiles rained down on millions of innocent Ukrainians, their president merited not a single mention because this violence was being unleashed by China’s staunchest ally, Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

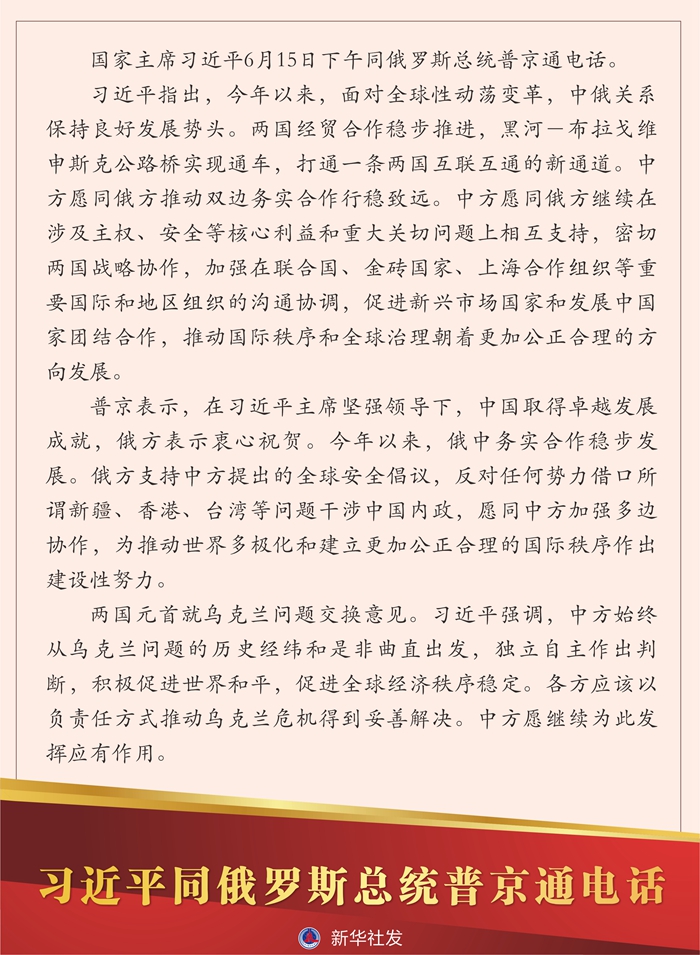

Last week, as Xi Jinping finally spoke to President Zelensky, four articles materialized in the People’s Daily within half as many days, signaling Xi Jinping’s ambition to position himself as a peacemaker in Ukraine. And as China now claims to be stepping up as a responsible power, it is critical to reflect on the obscure, constrained, and sometimes monstrously insensitive discourse of the Chinese Communist Party — and its possible implications for the world.

Sweeping Up After Lu Shaye?

One popular expert reading in the wake of Xi Jinping’s one-hour phone call last Wednesday with Zelensky, likely the first in 14 months, has been that this was damage control for careless remarks made on French television on April 21 by the Chinese Ambassador to France Lu Shaye (卢沙野), in which he outrageously questioned the sovereignty of former Soviet states — setting fire to perceptions in the European Union.

But China’s formal statement in late February of its “position” on the settlement of what it still insists on calling the “Ukraine crisis,” which came ahead of a month of active diplomacy that included the brokering of a landmark agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, suggests that however Lu’s antics might have shifted timelines (if at all), Xi Jinping has had peacemaking and its reputational benefits in his sights. In fact, that solitary mention of Zelensky last month, published in the People’s Daily on the very day Xi Jinping arrived in Moscow for his state visit with Putin, was likely a little red signal flare, CCP-style.

This game of speaking in code is part of the instrumental language of China’s Leninist ruling party. For generations, CCP leaders have been steeped in this specialized discourse, which serves to construct power, to conceal as it declares, and (as the case of Zelensky shows) to obliterate. In the Xi era, the discursive confections of the CCP have grown more elaborate than at any point in the reform era, as controls on speech have intensified.

In a keynote address at a Beijing summit of world political parties on March 15, Xi Jinping announced the formation of the Global Civilization Initiative (全球文明倡议). The CCP, he claimed, had advanced “the progress of human civilization” with its creation of “Chinese-style modernization as a new form of human civilization.” In turn, this would contribute to a process of global civilizational exchange that would “make the garden of world civilizations more abundant,” and lead us all to what Xi calls “a community of common destiny for humankind.”

This game of speaking in code is part of the instrumental language of China’s Leninist ruling party.

What happens when we pick apart one piece of circuitry in this elaborate verbal machinery? In his political report to the 20th National Congress last year, Xi Jinping elaborated on the promise of “Chinese-style modernization,” and made clear that its most fundamental precondition is “adhering to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.” So there we have it, lurking just behind another fanciful turn of phrase: the raw assertion of power and legitimacy.

These elaborate Russian dolls of rhetoric, painted with pretty phrases like “common prosperity” and “win-win cooperation,” may look to some in the outside world like real plans and strategies, an entire structure of responsible and well-thought-out proposals — even a “China solution” (to use another favored CCP buzzword). But they are always intimately connected to domestic power claims that have no business in practical and earnest deliberations over such important questions as peace in Ukraine.

For the world outside China, the real danger of this language is the way it obscures what China’s leaders have suppressed in their global vision as a reflection of their own repression at home — the individual rights set down in the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Self-determination. Peaceful assembly. Freedom of expression. In China’s formulation, all of these are subordinated to the vague and open-ended promise of “development.” The real concern is for the rights not of individuals but of nation states, which must engage internationally on the rudimentary basis of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and non-interference — which despite Xi’s claim to a “new form of human civilization” have all the conceptual freshness for international relations of antediluvian fossils.

Because the core of this language is raw power at home, and its further elaboration and justification through global ambition, even the base blocks can be rearranged when it suits the Party’s interests. China can ignore the catastrophic implications for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine of the war unleashed 14 months ago by its ally, Russia. And it can erase all mention of Ukraine’s president.

Solidity and Pure Wind

Now that Xi Jinping has opened channels to Ukraine and removed the country’s president from its long list of unmentionables, people like myself, who have established careers in the growth industry of decoding the CCP’s regimented language, are called upon to read through the obscurity. We ease back the layers, heeding the wisdom of one of the last century’s consummate readers of CCP-speak, Lászlo Ladányi, who urged us to, “Above all, read the small print!”

Ladányi also exhorted China watchers not to lose their sense of humor. “A regimented press is too serious to be taken very seriously,” he wrote. For anyone who tackles the April 27 readout on the call with Zelensky — who of course is famous for his sense of humor — this will seem sage advice.

The read-out begins with Xi Jinping thanking the Ukrainian side “for its strong support for the evacuation last year of Chinese citizens.” Immediately, the omissions loom large. Nowhere in the read-out is the word “war” mentioned, or Russia’s invasion, or Russia at all. Why, exactly, was it necessary to evacuate Chinese citizens from Ukraine last year? Can peacemaking really be entrusted to a power that cannot speak the word “war”?

Next comes the obligatory empty talk — which must have brought a chortle from Zelensky — about “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity” as the “political foundation of China-Ukraine relations.” China also claims to have “always stood on the side of peace,” though its role has been complicated, to say the least.

It is in the next line, as the read-out begins to outline China’s call for peace talks, that we descend straight down into remorseless CCP-speak. “We have successively proposed the ‘Four Shoulds,’ the ‘Four Togethers’ and the ‘Three Points for Consideration,’” it reads. China’s leaders cannot resist such formulations, because they can be packed and unpacked, stacked and unstacked, like boxes filled with imaginary things. A “Four Togethers” was already touted last year as Xi Jinping’s answer to online governance, accompanied by “Four Principles” and “Five Propositions.” But never mind. We can always imagine something else in those boxes. Such political language, as George Orwell wrote in an essay on the subject, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

Can peacemaking really be entrusted to a power that cannot speak the word “war”?

China’s former foreign minister, Wang Yi (王毅), introduced the “Four Shoulds” in March last year within two weeks of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The concept’s foolishness shone brightly against the bleak backdrop of Mariupol, where mass graves were being dug for the Ukrainians killed under intense Russian bombardment: The sovereignty and territorial integrity of nations should be respected; the purposes and principles of the UN Charter should be respected; all countries’ legitimate security concerns should be taken into account; and every effort beneficial to the peaceful resolution of the crisis should be supported.

Meanwhile, as Xi Jinping dialogued closely with Putin, the People’s Daily and other state media parroted Russian narratives about US and NATO culpability for the war, spent weeks on end blatantly spreading Russian disinformation about alleged US biological weapons facilities in Ukraine — and of course, put Zelensky on ice.

We could continue to ease apart the layers of CCP rhetoric. But at the core, we will find the same airy assertions — about a man, we are told, who has revolutionized Marxism for the 21st century, who is piloting his country back to greatness, and who deserves ultimate Party power and a third term as China’s head of state because the world is complicated, and what are we to do without him? Recognizing that the base logic is power, it will not surprise us to find that the Chinese read-out of the Zelensky call last week exploited the exchange to glorify the general secretary: “Zelensky congratulated President Xi Jinping on his re-election, praised China’s extraordinary achievements and said he believed that under his leadership, China would successfully meet all challenges and continue to move forward.”

Frankly Speaking

Once we are done squeezing sense and significance out of Xi Jinping’s “Maospeak,” once we turn from the grandiosity of his nonsense, we are left with the same challenging set of questions that stand in the way of peace. We can count on Zelensky, the comedian turned statesman, to treat them with the seriousness and frankness they deserve: “No one wants peace more than the Ukrainian people. We are on our land and fighting for our future, exercising our inalienable right to self-defense,” the President said during his call with Xi. “Peace must be just and sustainable, based on the principles of international law and respect for the UN Charter. There can be no peace at the expense of territorial compromises. The territorial integrity of Ukraine must be restored within the 1991 borders.”

Zelensky, his head beneath the clouds, also made a practical point that chastened China for its tacit support for Russia’s act of aggression. “Russia converts any support — even partial — into the continuation of its aggression, into its further rejection of peace,” he said. “The less support Russia receives, the sooner the war will end and serenity will return to international relations.”

With so much at stake for Ukrainians and the rest of the world, we should certainly welcome all genuine efforts beneficial to the peaceful resolution of the war in Ukraine — to follow, I suppose, the last of China’s “Four Shoulds.” But the Chinese Communist Party’s seeming incapacity to part with its obtuse rhetoric — so bloated with self-glorification, so turgid with over-promise, and so spectacularly arcane — is a serious impediment to international understanding that should itself be a cause for concern as China steps up its bid for global leadership.

Beyond distracting from rights-based values and encoding authoritarian ones in a bait-and-switch fashion (documented in the excellent Decoding China dictionary), this rhetoric invites deadly miscalculation.

In an article for Foreign Affairs in late March, former Beijing Bureau Chief for The Washington Post John Pomfret and former Deputy National Security Adviser Matt Pottinger wrote on the basis of their expert reading of four recent Xi Jinping speeches that the leader is “preparing China for war” in the Taiwan Strait. The article was an alarm bell. But responding one month later, a group of students, interns and former state media reporters on a well-known Substack account operated from China argued that the conclusions in the Foreign Affairs piece were based on misreadings of China’s politics, its press system and its odd official discourse, and that they fueled “an unnecessary sense of panic.”

The lesson I took from this tremor of discussion was just how impenetrable China’s official discourse in speeches and in the press is — not only to those with a deep experience of the country and fluency in its language as they gaze from the outside, but also to those reading from inside the country. And it occurred to me just how perilous our lack of clarity about China has become, a problem compounded by the CCP’s monopoly on expression domestically, which has obliterated individual voices and their moderating influence, and has condemned ordinary citizens to ignorance about their own society.

During his first months in power, Xi Jinping crafted an image of himself as a down-to-earth man of the people. He pledged an end to formalistic pronouncements and encouraged a more informal style among his fellow officials. This proved to be anti-bluster bluster. Since that time, Xi has compounded China’s political culture of grandiosity, placing himself atop a lofty pyramid of concepts created by a corps of Party discourse engineers below. Because the Party is so fixated on verbal monument-building, it has now even posited a distinctive “Chinese discourse system” for what thinkers like Zhang Weiwei (张维为), a key advisor, say will be a new era of “post-Western discourse.” It talks about a “strategic communication system with Chinese characteristics.”

The distinctiveness of CCP-speak is not a gift to human civilization. In fact, it is a growing international problem. An abyss of potential misunderstanding lies between the reprehensible rantings of Lu Shaye (a style Xi Jinping has nurtured among his diplomats) and the absurd “Maospeak” of mainstream CCP discourse. When experts wanting to know what China is thinking and planning must sort through page after page of florid obsequiousness in the People’s Daily, reading the small print, ours is a more dangerous world.

Speak plainly, Mr. Chairman. What do you mean when you talk about “peace”?