Last night, in a harrowing post to Chinese social media, an anonymous user laid out serious accusations against a male professor at Zhengzhou University, the country’s largest public university, alleging that he raped and manipulated her 11 years ago when she was just 16 — and that he later accompanied her to the hospital for an abortion.

“Hello, Professor,” the post read. “It’s been 11 years. Are you surprised I’m still alive? I’m so sorry to disappoint you. Do you still remember me? I’m the girl you brainwashed, that you mentally controlled for two and a half years, that you violated, that you destroyed.”

The professor was identified in the post as a faculty member at the university’s School of Marxism, who taught courses on contemporary Chinese Marxism and the theory and practice of socialism with Chinese characteristics. His accuser wrote that she had not previously come forward because she had been gripped by fear, shame, and hopelessness. “I know that justice will never come,” she wrote. “I compose this letter with the certainty of death, knowing that once the heat has passed, he will still be who he is. He will be the same professor who writes so well about socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

The post trended rapidly on social media. By early Wednesday, a chat thread for “Zhengzhou University Wang _____,” identifying the accused by name, had received more than 100 million views. A related thread on Weibo reached number eight on the list of hottest searches nationwide, gaining 1.2 million views and listed as “boiling” (沸) — marking it as one of the hottest trending topics on the platform [archived hashtag].

But even as it went viral, the plateauing of information about the Zhengzhou University case offered a salient illustration of how such posts are contained by the authorities in China — with the broader objective of guiding public opinion and ensuring discussions do not entertain deeper questions about the abuse of authority.

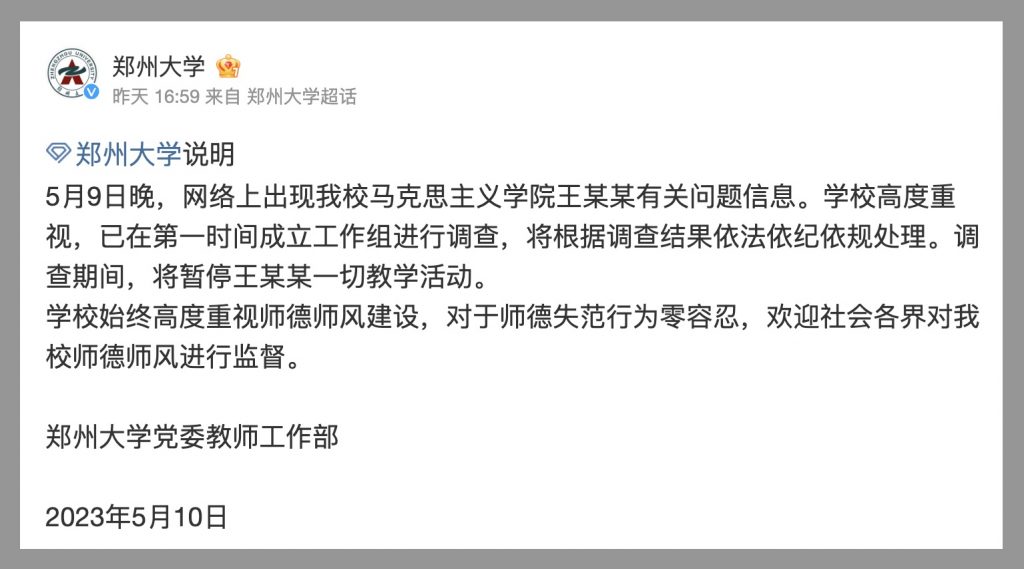

In the early hours of Wednesday, close on the heels of the original post, Zhengzhou University issued a response through its official Weibo account. The notice, issued by the Teachers Work Department of the university’s Party Committee, said that it had given the matter high priority, setting up a special task force to investigate. “The university attaches great importance to the construction of morals and styles among our teachers,” the notice said, “and has zero tolerance for moral misconduct.”

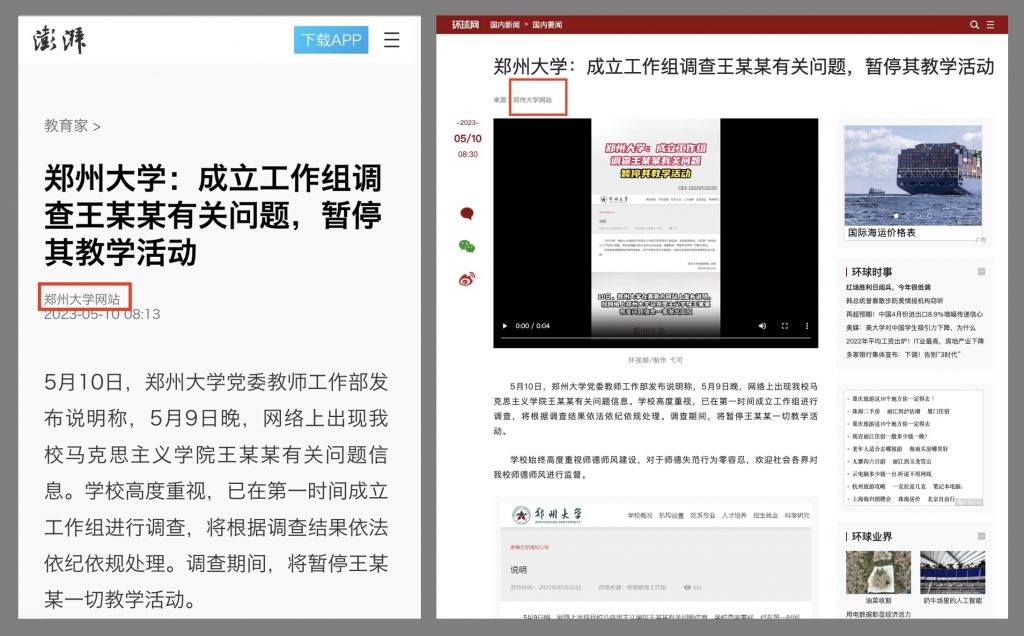

As the story was picked up early Wednesday morning by scores of media outlets, the coverage parroted the Zhengzhou University notice posted to Weibo and the university’s website. The majority of stories listed the source directly as the “Zhengzhou University Website,” or sourced identical news items from other media channels that referred to the Zhengzhou University notice.

Examples of this treatment of the story can be seen at The Paper, a Shanghai-based digital outlet under state-owned Shanghai United Media Group (SUMG); Global Times Online, the website of the Global Times newspaper published under the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily; CE.cn, the website of the Economic Daily, a state-owned newspaper managed by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department; the Shanghai-based news portal Guancha.cn (观察者); China National Radio; the official website of the Hangzhou city government — over 1,000 kilometres away — and so on.

The complete lack of follow-up by Chinese media, and the near uniformity of treatment, suggests that restrictions on the story were already in force by early Wednesday morning, instructing editors to use the Zhengzhou University notice only, and to avoid independent reporting. This would effectively mean the story was finished before it ever had the opportunity to develop — for example, through direct and personal interviews with the author of the Weibo post.

The complete lack of follow-up by Chinese media, and the near uniformity of treatment, suggests that restrictions on the story were already in force

There were only the slightest variations among the above-listed news sources. The story from China National Radio, for example, repeated the university notice verbatim after a simple lead that noted that “a web user revealed on the internet that 11 years ago they were PUA’d for two and a half years by a Zhengzhou University professor.” The term “PUA,” short for “pickup artists,” is popular slang on the Chinese internet for men who use cruel tactics to pursue women.

The version at the Global Times Online included a 10-second video that simply displayed the notice from Zhengzhou University and summarized the story based on the university’s release.

Of the news reports available online, the report from Shanghai’s Guancha.cn went furthest in reporting the nature of the allegations, noting after a lead repeating the university notice (and tip-toeing around the mention of rape):

On May 10 at around 00:00, a netizen posted on Weibo that she had been mentally controlled by a teacher at Zhengzhou University for two and a half years 11 years ago, and that he had taken her to the hospital for an abortion after a violation leading to pregnancy.

This small addition to the story, based on the original Weibo post, at least offered some indication, unlike most other versions online, of the exact nature of the accusations to which the university was responding. But the information was also inaccurate. The original post had been made hours earlier.

The only other point of slight variation in coverage came in the headlines added by some media channels to their reports as they copy-and-pasted the Zhengzhou University notice. At Phoenix Online, for example, nothing was added beyond the official university response. Nevertheless, editors did their utmost to grab the audience, stuffing as much sensationalism as they could into the headline of a story that deserved sensitivity and humanity.

“Woman Pregnant After Assault by Marxism Teacher? Zhengzhou University Responds.”