Journalists from the People’s Daily, the flagship newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party, march toward Tiananmen Square on May 17, 1989. The banner over their heads reads: “Eliminate Martial Law, Protect the Capital.”

When Xi Jinping addressed Chinese journalists on February 19, 2016, emphasizing loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party as the fundamental condition of their work, he spoke a phrase that has echoed across the now 34 years since the brutal murder of innocent students and citizens by government savagery on June 4, 1989. “Adhering to correct public opinion guidance,” said Xi, “is the heart and soul of propaganda and public opinion work.”

This concept that Xi describes as the “heart and soul” of press and information control in today’s China is about cutting out the real heart and soul of the people — ensuring not that the voices and demands of the population are heard, but that the undeviating voice of the Party dominates the life and politics of the country.

Underpinning all work to control information and public opinion today, from the latest commentary in a state-run newspaper to every comment on the most popular social media platform, “public opinion guidance” (正确舆论导向) reaffirms and focuses the CCP’s conviction that media control is essential to regime stability.

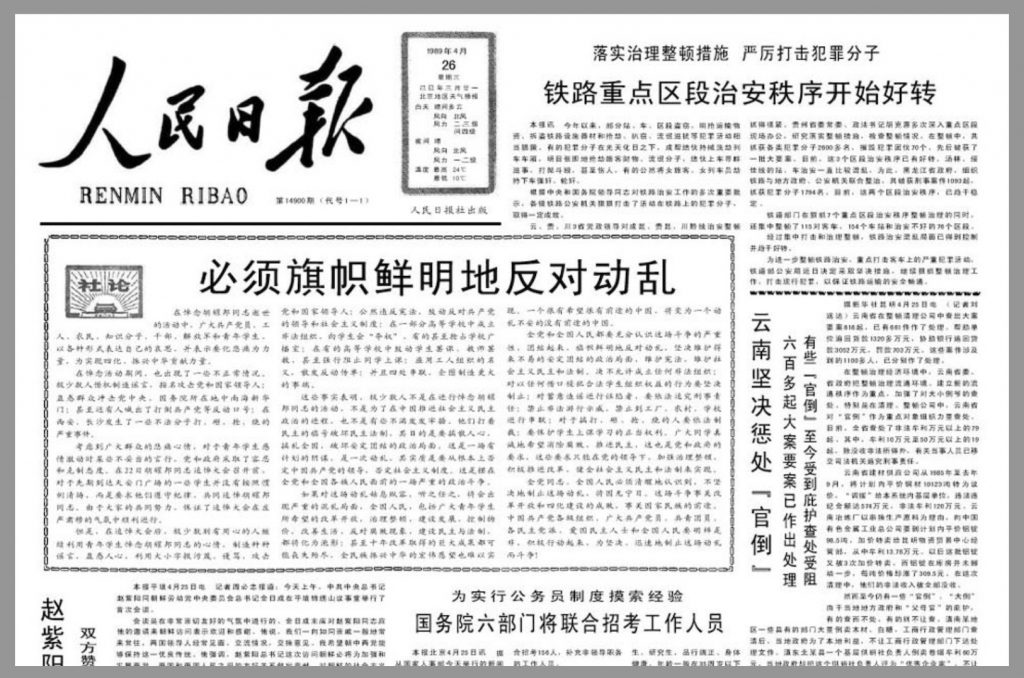

The concept emerged in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Massacre, as the new leadership under Jiang Zemin (江泽民) — who as Party Secretary of Shanghai had played a central role in the April shutdown of the country’s most liberal newspaper, the World Economic Herald (世界经济导报) — identified the factors leading to the unrest in Beijing and across the country. The leadership’s assessment centered on a meeting that Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳), the ousted liberal premier, had held with his top propaganda officials on May 6, 1989, ten days after the People’s Daily had published the infamous April 26 commentary (shown above) taking an attitude of zero tolerance and branding the protests as “an attack on the Chinese Communist Party and the socialist system.”

Zhao Ziyang had called for the rescinding of the April 26 editorial, which had angered protesters and further intensified an already tense situation. According to an account in China Comment (半月谈), a leading CCP journal:

In the afternoon, Zhao Ziyang spoke with officials from the Central Propaganda Department and others responsible for the ideological work of the Party. “Open things up just a bit. Make the news a bit more open. There’s no big danger in that,” he said, adding. “By facing the wishes of the people, by facing the tide of global progress, we can only make things better.”

In the aftermath of the massacre, it was the assessment of the new leadership, as reported in China Comment, that this moment between Premier Zhao and his top propaganda ministers had marked a fundamental failure. What happened next? According to the journal:

Once Zhao’s words were conveyed to news media through comrades Hu Qili and Rui Xingwen, support for the student movement rapidly seized public opinion and wrongly guided matters in the direction of chaos. Several large newspapers, television and broadcast stations in the capital offered constant coverage of the students’ wishes. Subsequently, movements nationwide begin to gather strength, and the numbers of participants swelled. Headlines and slogans attacking and deriding the Party also multiplied in papers of all sizes, the content becoming more and more reactionary in nature.

In this passage, we see the notion of “public opinion guidance” emerge as a renewed conviction on the part of a hardened leadership that the control of the press is essential to the maintenance of social and political stability. For the hardliners who prevailed in that fateful political moment, the upheaval that spring was first and foremost a failure of media policy. And that perceived failure would shape the Party’s approach to media and information for decades to come, right through Xi Jinping’s undisguised declaration of media subservience in 2016.

For the hardliners who prevailed in that fateful political moment, the upheaval that spring was first and foremost a failure of media policy.

The Heart of the People

Looking back today, what can we see of China’s press at this critical juncture? What did this “constant coverage of the students’ wishes” in major newspapers actually look like?

To get a glimpse, we pulled just one page from the People’s Daily, dated May 18, 1989, and labeled “domestic news.” It is a page full of heart and soul, reporting the voices on the ground as China faced critical questions about national affairs that impacted everyone.

At the top of the page is a large photograph of protesters marching with a banner that reads: “People’s Daily journalists.” It is an image of the same group of protesters from the newspaper pictured at the top of this article. The caption in the lower right-hand corner of the image reads: “On May 17, a number of workers from this paper march in the streets, expressing solidarity with the university students.”

To the left of the image, a story bears the headline: “The Heartfelt Patriotic Demands of the Students Are Reasonable, and We Hope the Central Leadership Addresses Them As Soon as Possible.” This was a continuation of calls published on the front page of the newspaper, expressing the hope that central leaders would respond substantively to the demands being made by students who were now on hunger strikes that had begun five days earlier on May 13.

The wishes in the article were those of the parents and teachers of students on hunger strike, who were sought out by the People’s Daily, and who expressed understanding for the students’ actions. “I think the students’ actions are justified and patriotic,” Zhu Renpu (朱仁普), a teacher from the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, told the newspaper. “It should be said that the central government is fully capable of satisfying [their demands], and should do so.”

In a personal expression of political conviction that would be unthinkable in any Chinese medium today, Zhu spoke about how he had come to sympathize with the position of the students, and to be moved by the nature of their actions. “At first, I didn’t understand the student movement, thinking they were being irrational,” he said. “But after going to Tiananmen Square several times, I found their slogans and orderliness to be truly moving. Not only were they rational, but they were also restrained. Their sense of concern and responsibility about the future and fate of the country is something we in the older generation should learn from.”

Such talk of “orderliness” went directly against the allegations in the April 26 editorial, which portrayed the students as destructive and chaotic. At this point, in any case, top Chinese leaders were nowhere to be seen. A key message in this report, as in many in the May 18 edition of the paper, was that they should come to Tiananmen Square and see for themselves.

“I sincerely hope that the main leaders of the central government will come out immediately to talk to the students,” Zhu Renpu was quoted as saying.

This extraordinary news story was written by Zhang Jinli (张锦力), who subsequently made a reputation for himself as a television presenter and expert in history — and now has a history-related channel on the short video platform Watermelon. At the time, Zhang was a young economics reporter for the People’s Daily, having joined the paper in 1986.

Can’t Leaders Guide By Listening?

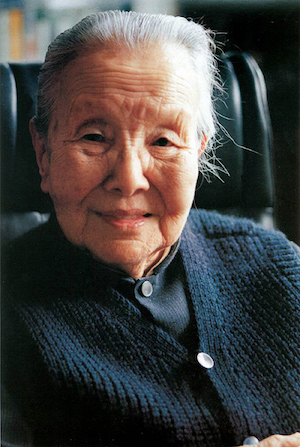

In the upper right-hand corner of page two on May 18 was an article called, “We Are Called the Parents of the People, So We Can Protect Our Children and Grandchildren.” This small contribution was written by the author Bing Xin (冰心), who at the time was, rather symbolically in retrospect, 89 years old. She had been born in Fujian in 1900, and had published her first essay 70 years earlier in 1919 in Shanghai’s The Morning Post, which had launched the previous year.

The headline of Bing’s article in the People’s Daily was taken from a couplet posted above the gate of a temple in her hometown when she was a young girl. “Now there are hundreds of thousands of my children and grandchildren suffering in Tiananmen Square,” Bing wrote. “When will this suffering end?” A parenthetical note at the end of the article read: “Urgently written on May 17, 1989.”

Bing Xin voiced her agreement with an open letter published by the presidents of 10 Beijing universities, calling on top Party and government leaders to meet with the students and hear their demands. She pointed the way to a form of “guidance” markedly different from the one that would emerge from the tragedy of June Fourth just over two weeks later:

I think that if only one or two major leaders of the Party and the government show up at Tiananmen Square now and say even one or two words of sympathetic understanding and knowledge to the hundreds of thousands of people, they will guide things in the direction of sanity and order, and then our children and grandchildren will not have to pay an unnecessary and heavy price.

As the journalists of the People’s Daily took to the streets to report on the demonstrations, and as they sought out parents, teachers, intellectuals, and others, it was clear that the heart and soul of the capital, the heart and soul of the nation, was with the students.

For the leaders who came to power in the wake of June Fourth, this was the lesson to be taken from the tragedy they never acknowledged: that “guidance” had to be the heart and soul — that it was perilous to let the people speak their minds.

… that brief moment in time when the People’s Daily was truly the people’s daily.

. . . . . .

In remembrance of the horrors of June 4, 1989, we finish with a humble celebration of that brief moment in time when the People’s Daily was truly the people’s daily.

The piece that follows, which appeared at the center of page two of the People’s Daily on May 18, 1989, just below the image of protesting journalists, is called simply, “They Must Come Out to See the Children” (应该出来见见孩子们).

_______________

At 2 PM on the 17th, this reporter’s car was stopped in mid-journey by a group of marchers. When I walked into the Yong’an Xili Neighborhood Committee in Chaoyang District [about four kilometers east of Tiananmen Square], several female cadres there were gazing out the window at the stream of people on Chang’an Avenue shouting slogans in support of the students. Anxiously, she said: “The central leadership should hurry up and come out to meet the children!”

If Premier Zhou [Enlai] was still alive, he would have come out earlier,” said Liang Yanyi (梁晏怡), director of the family planning committee of the neighborhood committee. Late last night, around 3:30 AM, she was still unable to sleep, and every time she heard the cry of an ambulance out on the street, she was saddened. “On the radio this morning, [I heard that] more than 600 of the university students going on hunger strike in Tiananmen Square had collapsed. They freeze in the black of night, and roast during the day. How can anyone who raises children feel anything but pain?!”

“I watch TV, and as soon as I see the university students being loaded onto ambulances, I break out into tears,” said Xu Fangling (徐芳玲), the neighborhood committee mediation director. “It is not easy for the country to train a college student. Their patriotic actions and the words they say arise from the hearts of the people and represent the masses. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and Premier Li Peng should come out quickly and meet the students who are on hunger strike in the square!”

As she saw groups of workers marching along Chang’an Avenue, the women’s director of the neighborhood committee, Dai Baozhu (戴保竹), said with concern: “We’re all so anxious. Thousands of families are concerned about national affairs. When the elder brother (the workers) has come, can his sister-in-law feel at peace? For the life of me, I can’t figure out why they [the leaders] won’t come out to see them. You can’t just hide. You can hide from today, but you can’t hide from tomorrow. The more you hide, the bigger the problem becomes!”

As she cut hair for local residents, Yue Zhimei (越志梅), the director of public security, chimed in: “The head of the central government should not be afraid of the masses. He should go to the square and see for himself the students who are starving.”

“We hope that the leaders become one with the masses,” local resident Ren Zangfen (任藏芬) said.

As we were all conversing, Dong Wenying (董文瑛), the director of the neighborhood committee, returned from an emergency meeting at the sub-district office. “We support the children’s patriotic actions,” she said. “The head of the central government must receive the children as soon as possible. They must be more responsible for the nation’s future. There must be no more delay.”

“Otherwise, they will be responsible for the future of China!”